TOM SANDBERG

Untitled, 2008, Tom Sandberg

The curator of the show Tom Sandberg: Photographs 1989-2006, Bob Nickas on his collaboration with Tom Sandberg.

Nina Strand After your first visit at Ekely in Tom's studio, set up by Marta Kuzma and OCA as a last-minute meeting, having encountered his big, haunting prints, you knew immediately that you wanted to make a show with him. What was it in his work that intrigued you?

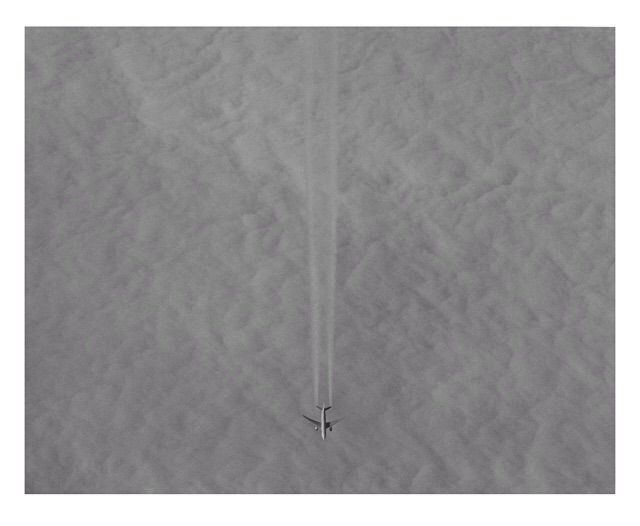

Bob Nickas Some of them were, as you say, haunting. The images stayed with me after I had left, and of course I thought of his pictures of planes and clouds and the sky on the flight back to New York. It was clear that this was an artist who saw the world in a way that emphasized its fragility and ours. One image in particular hit me very strongly, as I'm sure it does for most viewers—the enormous egg-like baby's head on the beach. That's a photo of his daughter when she was very young. You only need to see that photo once and you don't forget it, and that first time you feel as if you already knew it from before. Not many artists can create images with an instant recognition, and that linger for a long time. It could be a scene from a movie, where everything is still and then suddenly there's a slight movement, a little paw-like hand in the sand, and then the child attempts to lift its heavy head and can't. So there is also this filmic quality to Tom's work—all these stills from the movie that is life—and his downbeat film-noir sensibility is very evocative. For one thing, only black-and-white prints. Tom, like others who capture that halting stillness and its poetics, worked exclusively in black-and-white. I would suggest as well that in a quietly expressive way he was able to amplify silence. John Cage did that most famously, and it's worth noting that among Tom's portraits of artists is a very fine picture of Cage from 1985. Here, Tom seems to regard a person no differently than he would the face of a mountainside.

NS In your catalogue text you make comparisons between Tom's pictures and Peter Hujar's, and wrote: "Tom Sandberg’s is a world where life is always in the balance; we are in it, but only in passing. We can experience an intense connection to it, and share it with one another, and at the same time be awed by how insignificant we are in relation to its vastness." The show at PS1 was so well put together. How was it to collaborate on it with him? You organized several exhibitions with photographers. How did you see Tom's work in comparison? And how was the show received?

BN In my text I also refer to Edward Weston, Weegee, Robert Frank, William Klein, and Brassaï. That's very good company in which to be included, but also for them to be in his company. While the art of the past helps us to understand the art of the present, so too can the art of the present inform what came before. Time is never really moving in one linear direction, and histories overlap. In Tom's case, this may have something to do with the timeless quality of his pictures, the sense that their position is not so easily fixed. What year is it? And is it night or day? In the end, this doesn't really matter. Like the ghostly image of the plane that seems to float above the runway, the pictures hover in time. Tom and I occasionally met in Paris, and on one occasion I was celebrating my birthday, for which Tom gave me Henri Cartier-Bresson's Scrapbook. Maybe if we had been in Oslo or in New York it wouldn't have registered in the same way, but because there was such a strong connection between the pictures and the place, I felt as if the activity represented in the book, that pursuit of the world in passing, its sadness and its mystery, what was known and unknown, was also Tom's activity.

The other photographers I had previously done shows with at PS1 were William Gedney and Peter Hujar, who were no longer alive, which meant that I was dealing with pictures and not the person who made them. There was an exhibition with Stephen Shore, we showed an entire series and hung the pictures almost exactly as they came out of the crates—a very democratic process. With Wolfgang Tillmans, although his plan was based on my invitation and our initial conversations, he is in many ways his own best curator. He had very definite ideas for what he wanted to do, and an overall vision for the show. Around that time I proposed to bring a survey of Louise Lawler's work to the museum, but she decided against a big New York show in that moment. So the exhibition with Tom turned out to be my last at PS1. It was easy to work with him. We respected one another and he trusted me—in part because he was somewhat nervous and I was totally confident. I knew it would be good from the beginning. There were a lot of great pictures to choose from and we had plenty of space. The show was given the largest galleries in the museum. I think he was curious to see how someone else responded to his work in the choosing and installation of a show. As the works were placed and hung, everything was discussed between the two of us, and we were both happy with the results. Many who came, including otherwise well-informed critics and curators, couldn't help wondering how it was they were unaware of Tom's work, and it was clear that his pictures had made a very strong impression. Despite the fact that he had been working for some time, his art was very much a discovery in New York.

NS For this issue we have invited a number of artists to have conversations with each other on the state of photography after Tom. One predicted that Tom's pictures will stand out even a hundred years from now as the work of Munch does. Two artists are also looking at current trends, and are very pessimistic, stating: "All we see are repetitions of previous work. Different varieties of something old, out-dated and worn out." We are curious on your thoughts on both Tom's legacy and the work seen today?

John Cage, 1985, Tom Sandberg

BN Who can say whether Tom's work will stand a hundred years from now? Anyway, none of us will be around. And yet if you look at what contemporary picture-making concerns itself with today, it's doubtful that it will somehow captivate people in the future. It's not so fascinating to us now. The sort of calculated realism/surrealism you see nowadays, with oddly combined objects photographed against various color backgrounds, or manipulated with cheap effects, they may look strange or surprising on first view, but tend to flatten and appear more normal every time after. A hundred years from now, maybe two years from now, they may be mistaken for advertising or design.

As for Tom's legacy, I suspect that people will come back to it over and again. It will continue to be discovered and re-discovered, for at least as long as people remain interested in art, and in how we attempt to make sense of passing through this life.