ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

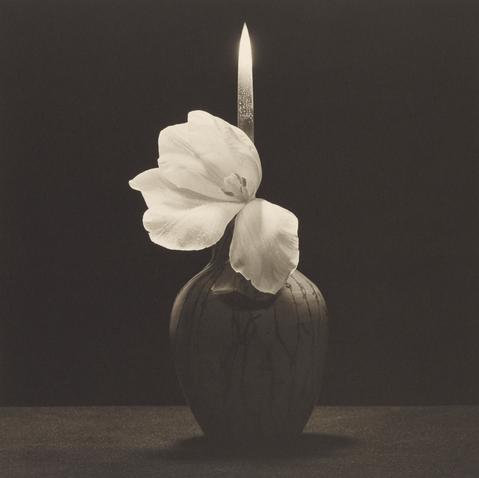

Robert Mapplethorpe, Flower With Knife, 1985. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

When I work, and in my art, I hold hands with God.

—Robert Mapplethorpe

You can’t hold hands with God when you’re masturbating.

—Anonymous

Review by Travis Diehl

Set aside the virile entendres of pistil and (mostly) stamen. The toned eroticism of Robert Mapplethorpe’s flowers also bear a funereal defiance. Flowers die. Photographs of flowers, less so. Imagine the Barthes of Camera Lucida poring over photos of the dead, in which their mortality is always both accomplished and impending. We can say as much for the subjects of what Mapplethorpe charmingly called his “sex pictures” as for his orchids; the notorious X Portfolio of 1978 appeared alongside its double, the Y, an equal number of prints of blooms. The heat of human and vegetable fecundity alike are locked in the preserving chill of the artist’s formalism. This is the price of persistence. Mapplethorpe’s embalming classicism would defeat the fixed mortality of his subjects—himself among them. In the 1985 still life Flower with Knife, a naked blade flickers from a vase, splitting the frame; in a 1983 self-portrait, the artist recoils like a street fighter, menacing a switchblade at an invisible threat.

Both photos appear in “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium,” the double retrospective on view at the Getty Museum and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Of the self-portrait, part of the Getty’s hang, a wall label directs us to a 16th-century painting by Caravaggio, Boy Bitten by a Lizard. (More apropos than a reptile is Caravaggio’s fatal penchant for duels.) This is one of the least direct citations. Mapplethorpe rose to fame with an art posed between porn and décor—and often anchored it with historical aesthetics. The artist said of his X and Y portfolios that he saw no difference between a fist in an ass and a carnation in a bowl. This depends on their mutually strict, centered composition. Other references are more explicit: in addition to photos of actual statues (Female Torso of 1978, for one), the tetraptych Ajitto, 1981, a black man on a pedestal, reimagines Hippolyte Flandrin’s 1836 Nude Youth by the Sea from four angles; in Lydia Cheng, 1985, the model’s well-defined form is painted bronze.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ajitto, 1981. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Such performative decadence extends to the self-portraits. The dozen in both shows (the artist made many more) punctuate the phases of Mapplethorpe’s career with the roles he played. Two self-portraits introduce the LACMA : one, from 1977, shows the artist in makeup and fur; it shares a wall with the campy, cowboy-themed semi-nude Victor Huston, 1978. The second, from 1980, featuring Mapplethorpe in a Lou Reed getup complete with sneer and cig, centers two groups of photos of bondage, leather, and s/m friends and acquaintances, including the tactile black encasement and coruscating sheet plastic of Joe/Rubberman, 1978. At the Getty, a self-portrait portends the end: in Mapplethorpe’s famous 1988 image, a bony hand clutching a skull-topped cane rushes forward; the artist’s sallow face floats beyond the focus plane. This forceful premonition has almost become a cliché. The LACMA hang concludes with a wall of photos of the photographer taken by his contemporaries—as well as, in a garish blue frame, Gillian Wearing’s bloated self-portrait as the dying Mapplethorpe.

At the beginning is Self-Portrait, 1970: young, bare-chested, Mappltehorpe fingers his necklaces; red spots outline his silhouette; green and pink paint block out the margins. This early collage, made when the artist was in his mid-twenties, hangs at LACMA among a vivid range of juvenilia, from smeary gel transfers of physique mag covers and photo collages which evoke the rubbery distance of shrinkwrapped porn, to a group of wall-works made by stretching fishnet shirts and spandex underwear over frames. Most macabre is Tie Rack, 1969, a drawing of the Virgin curtained by black ties; blood drips fang-like from her mouth, while a crucifix on a black string hangs from pins driven into her stigmata. The tension between catholic composition and punk sentiment figures the carnal formalism of Mapplethorpe’s mature work. To the left of the 1970 self-portrait is Untitled, 1970, a drawing of a sort of head on a post, perhaps the prescient cane itself. To the right is a selection of Mapplethorpe’s handmade jewelry. The cruciform becomes, in one necklace, a tapering, dangling phallus of beads, bracketed by two grinning death’s heads.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1985. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe’s jewelry was both a fashion declaration and an early commercial venture. Both museums devote considerable space to celebrity portraits. At LACMA, introducing a wall of slick portraiture of the likes of Andy Warhol and Kathy Acker, is Self-Portrait, 1986: the artist turns entreatingly, in slight profile, his hair grown a bit thin, above the gutters of a sharp seersucker jacket. Around the corner, LACMA makes the most comprehensive (and requisite) survey of portraits of Patti Smith. The Getty’s picture of a smiling Louise Bourgeois, carrying her 1968 sculpture Filette, is matched in severed vicissitude only by the ambiguous gore of Dick, N.Y.C., part of the X Portfolio. This deathly glamor is foreshadowed in nearby rooms by a few still lifes of luxuries—chiefly from the collection of one Sam Wagstaff, Jr., Mapplethorpe’s lover and first patron. (The Getty’s installation segues into two rooms of works from the Wagstaff collection, which he sold to the museum in 1984, effectively founding their photography department. The present retrospective is occasioned by LACMA and the Getty’s joint acquisition of Mapplethorpe’s own archive.) Most striking is Ice Bucket and Spoon, 1987, a rough-hewn faceted silver bowl, decked with metal icicles. In Mapplethorpe’s masterful photo, the mountainous tones of the ice outshine their vessel.

For contrast, see Mapplethorpe’s fumbling Polaroids of the early-mid 70s—before Wagstaff gave him a Hasselblad. Yet the Getty hang, in particular, reinforces the virtues of Mapplethorpe’s exacting skill—the “velvety blacks” and “creamy grays” that, as much as his subjects, became his signature. The Getty offers, side by side, two prints of Coral Sea, 1983, a rare and perversely vertical composition of a warship nestled below a grainy, near-abstract horizon. One is commercial gelatin silver paper; the other, clearly richer, more satisfying, is platinum on cotton. This demonstration is meant to showcase a mature sense of perfection; as the gray sea blends into gray sky; LACMA’s full wall of nude African American men (more or less abstracted) read less as radical, pornographic, or worse—exploitative and negrophilic—less about skin color than skin tone. Both shows, perhaps by default, trouble how perfection might eclipse the hard-edged brutality of perfectionist methods. At the Getty, adjacent the stereotypically fetishistic black stiletto of Melody (Shoe), 1987, is another elegant but ominous image: a clay profile of Mussolini swept into the round (Continuous Portrait of Mussolini, 1988). The sculpture was part of Mapplethorpe’s own collection. Here is the fascist extent of Italian neoclassicism, a deadly, nationalist s/m. Hung to the right is a 1985 self-portrait of the artist jerking his head so as to render his own features as a similar, futurist smear. That the self-portrait predates the Mussolini head returns both photo (like most of the rest) to the boundaries of a sometimes experimental, always aesthetic perfection—technical, and not political. The social hangups of our era rinse away like paint from the denuded marble youths of Western antiquity—like flesh from the immortal, ideal form—or, for that matter, like the sexual tastes of emperors.

Some of Mapplethorpe’s images remain irreducible. The X Portfolio is nearly forty; yet, as Holland Cotter points out in his review, the New York Times still won’t run most of those photos. Mapplethorpe also made nudes of children, as richly printed as the rest; there is no mention of them here. Meanwhile, America’s culture warriors have moved on from their blood-boiling obscenity trials to bicker over the right to refuse gay customers a wedding cake. So what of the intervening four decades of sex? Mapplethorpe at LACMA transitions into “Physical: Sex and the Body in the 1980s.” Perhaps the bloody, tied-down Dick, N.Y.C. made possible the erotics of Mike Kelley’s Torture Table, 1992, whose materials are listed as: Wood, buckets, knife, and plastic pillow. Of the more traditional photographs, Laura Aguilar’s diptych Untitled No. 17, 1991, from her “Clothed/Unclothed” series, shows two women standing skin to skin; the portrait figures the embracing prom kings of Mapplethorpe’s Two Men Dancing, 1984. Both are far more intimate than a diptych of the artist and Wagstaff (Portrait of Sam Wagstaff, Jr., and Untitled (self-Portrait) both c.1974), where, in identical compositions, each clutches a white brick wall like a surrogate lover.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1981. Promised Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“The Perfect Medium” invokes “The Perfect Moment,” the retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s work that opened in late 1988, months before his death, and that would prove one of the Culture Wars’ hottest flashpoints. Mapplethorpe’s enemies on the right took a rigid view of sin. For his part, the photographer, whose Catholic faith passed into classical perfectionism, could not resist the occasional satanic innuendo. In Self-Portrait, 1978, one of the few photos on view at both locations, Mapplethorpe casts himself as a leathery devil; his chapped ass to the camera, he slides a bullwhip’s handle, tail-like, into his anus. The photo is taunting, brave, and knowing—hot, but not humorless. Mapplethorpe turns his head to the viewer; a rare sprout of goats’ beard on his chin, formally and otherwise, plays with the shade of his pubes. Such shadowings cut Mapplethorpe’s boldest irony with a tongue of doubt. We all die; some of us know it; and others are determined to outlive death. Mapplethorpe, before wearing monks’ robes around his apartment, before his self-portraits evinced the progression of HIV/AIDS, long before his ashes were interred in a family plot at a Catholic cemetery in Queens, was already covering his grave with flowers.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-portrait of Robert Mapplethorpe with trip cable in hand, 1974. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation