DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN & LUCAS BLALOCK

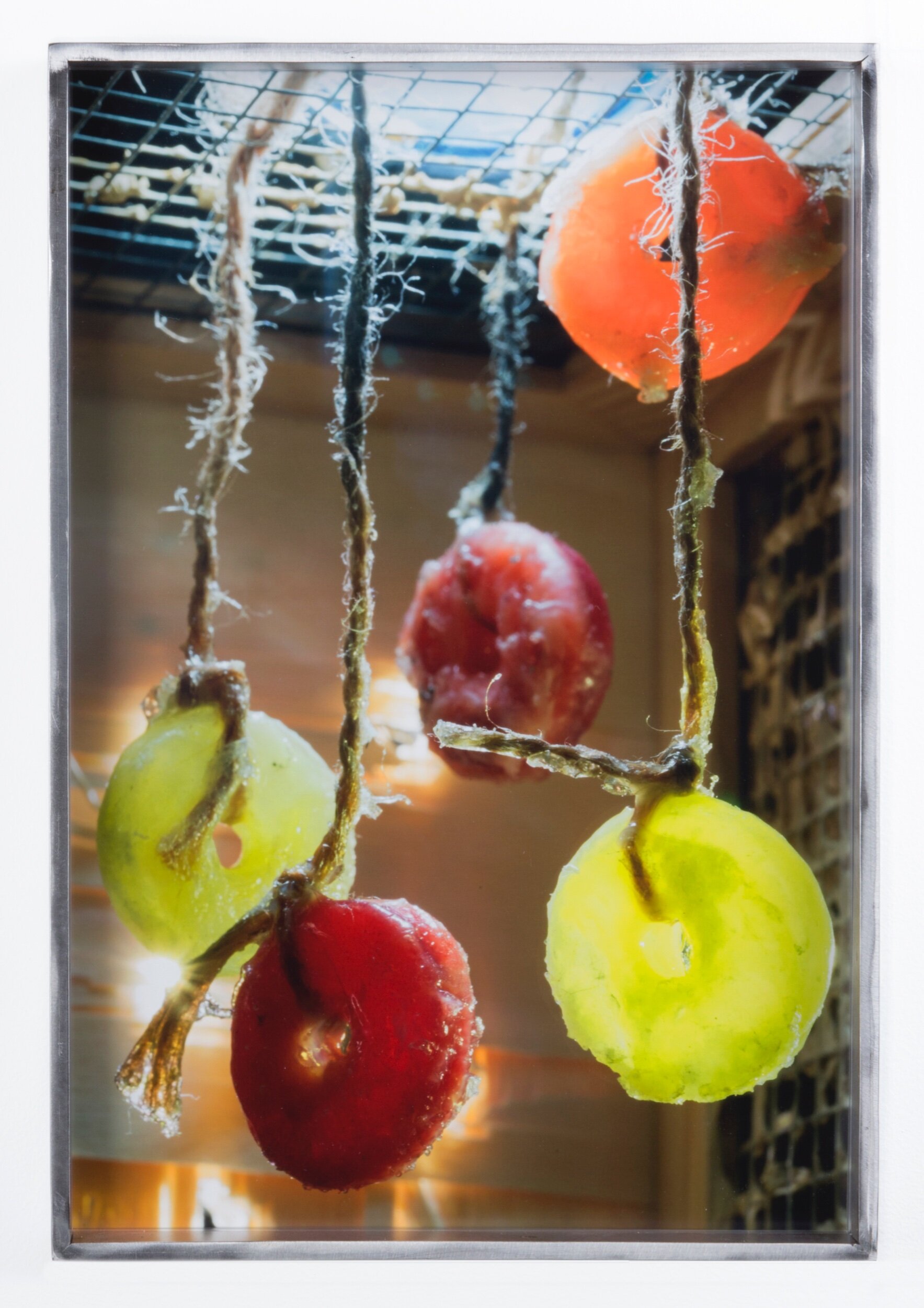

Flesh before Body, 2019. All images here are by Diane Severin Nguyen.

ANIMAL, VEGETABLE, MATERIAL

A conversation between Diane Severin Nguyen and Lucas Blalock.

I met Diane Severin Nguyen last August as she was passing through New York on her way back home to Los Angeles having finished the second of three summers on the MFA program at Bard College. Torbjørn Rødland, an enthusiastic advocate of Nguyen’s work, had suggested we meet. Nguyen’s visceral, materialist approach stayed with me. So last winter, when the 28 year-old artist was staging exhibitions of new work in both New York (at Bureau) and Los Angeles (at Bad Reputation) I was thrilled to catch up with her and talk more about her pictures, their fugitive subjects and how these two exhibitions came together.

Lucas Blalock I want to start with a general question about the impulse to make these pictures. Where do they come from?

Diane Severin Nguyen It comes out of a desire to juxtapose physical tensions and the failures of their linguistic counterparts. Sometimes words can claim entire bodies with their symbolic force, but sometimes they’re nowhere near enough. Working within a non-verbal space can bring about very specific material qualities relating to touch. I work from these minute tensions, of being pressed on, pierced, pulled apart, submerged, falling, twisting, which are often related to pain. And I’m curious to see if they can be empathised with photographically, or how they can be transfigured into a different feeling.

LB The images are kind of ‘grunty’: they present more as sounds than as words. And this can be set in opposition to the central activity of the camera, which has been to show things clearly in order to enable one to name a thing.

DNS There’s a poetic impulse in that sense to rearrange the language, because photography’s claims to representation and the real should be the departure point for an artist. There’s also a lot of political potential in being immersed in a medium that claims so much accuracy, which helps me think through many different texts that deconstruct essentialist approaches. For instance, my title for the show Flesh Before Body at Bad Reputation came from Hortense Spillers’ words: before the “body” there is “flesh”. Which is to say that before there’s this symbolic unit there’s the substance that makes it up and fills in the parameters of the symbolic unit, and how that dis-individuated life-form is what makes possible the individuated one. So I began to ‘flesh out’ this naming process that the camera relies on for its power, and work against its trajectory of naming bodies by starting with the nameless. I was also thinking about the word ‘impressionability’ through this other text I was reading, The Biopolitics of Feeling by Kyla Schuller, which in one section emphasised the difference between the elastic and the plastic. When you apply force to a material that’s elastic, and then you remove that pressure, it will return to its original form. When you pressurise something that’s plastic, it will be permanently changed. So there are certain words that describe these physical tensions, and how they might affect consciousness.

LB Plastic strikes me as a very sculptural term, but you’ve folded these concerns into photography. Can you talk about the delimited space of photography in your work?

Wilting Helix, 2019.

DNS I like approaching photography as a set of limitations, and also as something problematic. It forces me to begin art-making from a non-safe space, and reckon with this very violent lineage of indexicality, the pinning down of a fugitive subject in order to understand and place it. But when those tools and thought processes are exhumed or applied uselessly, we can make this Cartesian method less confident of itself. To accept the impossibility of ‘knowing’ takes us somewhere else, perhaps a more intimate place.

LB The connection to the fugitive subject is really apt because your material choices seem to be directly addressing this kind of pinning down. There’s something about fragility or flow that comes up over and over again in your work.

DNS I think it’s a lot about the provisional – almost like a material or bodily extension of ‘the poor image’ as proposed by Hito Steyerl, but actually enacting that in all of its precarity. Materials and bodies slip in and out of contexts, permeable to the elements but also political contexts. I try to echo materially what I find unstable about images, and I try to observe how materials are photographically disfigured, alienated from ‘native’ environments. I try not to rest in the place of sculptural object-making for this reason. A moment of re-birth relies on the possibility of everything shifting at once.

LB Yes, in object making, the thing is in the room with you and has to behave and remain stable, whereas the space of photography and of pictures has another set of possibilities. To me, it sounds as if you’re kind of using the photograph against itself. You’re talking about its history of violence enacted through this objectifying tradition of isolating and making a subject.

DNS It’s like a process of essentialising. Which is problematic, but I see it everywhere around me. I guess the photograph has always been used in this way, but I see people trying to assign their identities optically. And I find this to be a dangerous space. I thought we’d worked past this, but maybe we’ll never work past it.

LB There is this other way of looking at it that suggests some potential. Because we’ve used it as a parsing machine or an indexer, there’s a way in which we’re willing to read the photograph back into a bigger space as a portion of ‘reality’. This is something we don’t often do with objects.

DNS I think the reason why I’m not interested in claiming the sculptural labour in my work (even if I enact a certain kind of material experimentation) is because I’m too aware of the dispersion, the loss of authorship no matter how detailed the attempt – the permeability of an image. There’s a certain relinquishing with photography, a constant referent to an Other. And there’s a certain ownership with sculpture as an artist. I think what I’m doing is in dialogue with that dispersion, knowing that it will circulate. Even as I’m slowing it down, it’s in reaction to knowing how images can be sped up, over-circulated. But I have to be on that time scale, and the moments I harness in my work are surrounded by that anxiety. They try to reference it.

LB When I look at your pictures, I'm aware of this sense of threshold, both between the interior and the exterior, and between the animate and the inanimate. It’s something that has a particular resonance with the photographic. I was wondering if you could speak to this: how you see these thresholds, and if it’s something that you’re actively interested in?

DNS I’m always thinking about ‘life’ in this very big way, wondering how and why it’s so unevenly designated. And photography plays a crucial role in such constructions. By working with these ‘still lifes’, a traditionally inanimate space, I’m allowing myself to study the bare minimum requirements for ‘life’ to be felt. Ultimately, I’m not interested in assigning binaries between the organic and the inorganic, or indulging in the ego of an anthroprocentric status, which just recourse to human centeredness in a particularly Western way. The suspension I try to invoke is that it could be both or neither. Somehow, when the human body is removed, we get to start more immediately from a place of ‘death’, which I think photography serves much better.

LB It feels less like a trade between the terms than like a membrane, as if elements are threatening to shift into the other space.

DNS Yes, that precariousness feels so inherent to the medium itself, the rapid swapping of reality and perception. And I’m very invested in having photographic terms converse with this ‘language of life’. I believe that they’re born out of one another. Maybe this is a very Barthesian way of approaching things.

LB Can I ask you to say a little more about that – the ‘photographic language’ and the ‘language of life’?

Co-dependant exile, 2019.

DNS For instance, I’m always creating these wounds and ruptures for my photographs, this broken-ness which I think speaks to what a photograph can do to a body or to the world. But I’m also speaking to this photographic concept of a punctum, and wondering if it relies on the excavation of ‘real’ pain within a social space. I’ve depicted these evasive ‘wetnesses’. I really see photography as this liquid language, literally and materially being born out of liquids. But also, socially and economically, photography is liquid in that it can shift in value very quickly. Symbolically, liquidness can represent a very female substance and that potential immersion, like within a womb space. Historically, photography’s terms were developed alongside psychoanalytic concepts, Impressionistic painting, advertising, military technologies, and they continue to generate from/with these other sets of vocabularies. Within contemporary art, I really see the confluence with sculptural terminology as well. I guess I’m working with all those terms and trying to translate them materially.

LB This ‘evasive wetness’ you mentioned, or the way fire or burning or char act as subjects – it feels as if there are a number of ways or methods by which you get me as viewer into this prelinguistic space. One of them seems to be describing certain kinds of chemical or physical reactions.

DNS These elemental qualities provoke or catalyse moments of becoming or un-becoming. The elements speak to pressures and their transferences into new forms. Traditional Chinese medicine has a whole logic built around these types of transformations, and there’s definitely a primordial aspect to them that’s pre-linguistic. Again, it’s not revealing the ‘natural’ that I’m interested in, but more all the adjacencies that can be triggered by a photographic moment. For instance, studying photography made during the Vietnam war is fascinating to me, an era when 35mm film cameras and toxic chemicals were mass weaponised in conjunction with one another. On one hand, we have this Western-liberal pro-peace photojournalism; on the other, we have something like napalm, which is incredibly photographable. So with the fire in my images, I recreated napalm by following an online recipe. It burns in a very specific way. It’s sticky and can be spread into the shapes that I want. It lasts longer; it waits for me.

LB This makes me think about the myriad of histories you’re drawing together. Photography was certainly part of the toolkit that set the scene for the secularisation of the world and the rise of our current era of scientific, technological understanding. And this of course was produced through forceful displacements. Looking at your pictures I think about these adjacent traditions that have a stake in patterns that aren’t so ready to celebrate this turn: namely alchemy and science fiction. I’m wondering if either of these lineages play into your thinking?

DNS I like this idea you’re proposing of science fiction opposing secularisation or being displaced by it. Maybe the displacement is the part I relate to the most, the space of disaster that science fiction is always addressing, and the kind of resourcefulness that’s required in those conditions. Again, with the Vietnam War, the North was at such a great material disadvantage and couldn’t disseminate photographs at the same rate as Western-backed forces. There was a small agency set up by the Communists to glorify Vietnam through images, but the small number of war photographers would each receive a smuggled Russian camera and have something like two rolls of film for six months. There wasn’t the privilege of ‘choosing later’. So the results ended up being incredibly staged and remarkably ‘beautiful’, a twisting of poverty and political agenda. That sort of desperation to make an image that communicates is something I relate to deeply. And it’s how work in a sort of literal way, this grasping. It’s muchless rational than it should be really. It’s more desperate than I’d even want to admit.

LB I relate to that a lot. So in some ways maybe the alchemical aspect is closer because it shares a thirsty quest for knowledge.

DNS It is alchemical, though I’m not sure to what end, besides the image. But it’s also just me conducting bad science experiments. Everything is in the realm of amateur. Which I also find interesting in the space of photography. I find that echoed in what photography is: the accessibility of it and its amateurish qualities, its ‘dilettanteness’. The thing is, if I was a really pro ‘maker’, I wouldn’t be making photographs, so it’s about what I can’t do as well.

LB I understand that. It’s funny though because I hear the way you’re channelling this amateur quality, but there’s also something really seductive about the pictures. Particularly the quality of light. There’s a real fullness to them. You’re not a ‘Sol Lewitt / conceptual art’ amateur. You’re doing something else. Could you talk about that?

DNS It’s the amateur imagination, an amateur expertness. There’s a deep subjectivity to my work, and an emotion that I want to convey that usually has to do with the things that I can’t convey, and a constant attachment to that loss, like melancholia: what can’t be conveyed through a photograph. The images arespeaking to the fact that they can only exist under these terms and under these lighting conditions. And then without me, or me without them, there’s nothing. So the lighting is also very provisional. I’ll use my iPhone flashlight and I’ll use anything that’s around. have an aversion to studio lights, and everything is in this small scale. I appropriate lighting in a certain sense, looking at how light creates different situations. And it becomes a personality of its own in the way that light disturbs time. Even when I use natural light, a certain time of day, it should be an in-between moment. I think it speaks to this journalistic mood that I’m working into, even though it’s very staged. The mode is the capture.

LB Can you say a little bit more about this, because I love this idea of journalism in your work.

Pain Portal, 2019.

DNS I’m obviously aware of the lineage of journalism and it’s probably what I’ve always worked against. There’s some deep-seated aversion to street photography. But I can’t escape it, and I realised recently that this is the very mode that I take on. What does this mean for me to set up these fugitive subjects, to recreate this model of violence and photograph it? I need to admit to myself that this is the moment that I work with. And so, the more I delve into that, the more I find it a way to speak to that directly. That mode of capturing a temporary state of being is something that photography can do really well.

LB This is all coming through very clearly: the encounter in terms of subject and also in terms of picturing trauma, the sense of possibility in the provisional, and the passing ability to see. One of the things that I thought a lot about in your show at Bureau was the tension in the work between the seductive and the repulsive. There are things that actually feel traumatic – even forensic moments. But then there are other pictures where there’s much more of an invitation. I started to think about this group of situations as elements from a kind of nature film, in your attempt to capture this greater thing, a spanning from something that’s beautiful and what we might see, in the natural order, as grotesque.

DNS I think that there are these different moments of propaganda and emotionality that I’m trying to express. And it comes through in the actual installation of the images, where I worked more poetically than, say, essayistically. The way that I view a body of work holds this concurrent repulsion and beauty and different levels of accessibilities. I don’t really make these distinct series in a traditionally photographic way, but view the body of work as an actual body and part of a larger body. But I would say that most of the emotionality comes from trying to contain all the life within one image. Each image can operate on a really individual level.

LB One of the things that ‘drives them home’ is this sense of the irreversible: that though these objects themselves might not easily show what they are, it’s evident that the processes they’re going through can’t be fixed.

DNS You asked earlier about the science fiction and I wouldn’t say that my work is about any lived past or any lived future. A future is tethered to a narrative progress, which I’m really not interested in. But I do think a lot about the concept of the future of trauma and what happens during and after an event. Trauma, and how it’s rendered as an image that reoccurs in this tension that I’ve spoken about between the material and immaterial, this ordinary and potential moment – all those things add up to this kind of irreversibility. Also, at the core of my work is a deep desire to de-essentialise everything; to not let anything be trapped by someone else’s knowledge of it. So that irreversibility speaks to there being no state of purity to return to. That’s what I’m into, the non-purity.

LB The way you just described it makes me think of the tradition of vanitas. Because in a sense it’s a still-life practice you’re working through and I’m curious to read the images as still lifes engaging questions of mortality or passing. I mean a vanitas that’s denatured, pre-linguistic, more sensory than symbolic.

DNS They’re very self-portraity in a lot of ways. They’re more in that tradition than anything. They’re making active lives. I do get asked if I work in the lineage of still life and I would say that I’m only working from that to understand something else.

LB Even asking if it’s still life doesn’t feel like a good way of approaching it.

DNS The more I think about that term, the more I think about how it has this political relevance: what does it mean to have a still life?

LB Initially it was a presentation of wealth and painterly acumen. I think a lot of the things you’ve been talking about are in some ways in direct opposition to this tradition.

DNS But it is nice when things get condensed into a moment of stillness. When new changes happen, with me embracing the distance, or holding on to a physical tension that’s provoked by distance from the thing itself. That’s all within that vocabulary.

Malignant Tremor, 2019.

LB I think that this whole idea of the provisional that you’re bringing into your photography makes it so that the stillness is actually achieved in the picture making, which is different from still life. Still life will kind of stay there, whereas this is an interruption of flows of various speeds. It feels very central to the work that something is coming unglued.

DNS I think the touch of the pictures reveals a certain force that’s applied by me, the artist, in order to create this still-life. Which hopefully brings their stability into question, and also my intentions as an arranger. To me it’s a way of holding two positions at once - as a deconstructive critic of the apparatus but also as a highly subjective human artist.

LB You had two exhibitions this year, one at Bad Reputation in Los Angeles, and a two-person with Brandon Ndife in New York at Bureau. Are these two projects part of a body of work or do they feel separate for you?

DNS They were instigated by the installation requirements and conditions, by these two different spaces. I thought around those things. Obviously, it was interesting showing with Brandon because there’s this sort of content forwardness – his work also is also quite photographic in its stilling of things. With Bad Reputation I installed a circular window in the room, which is very small. There’s a more immediate relationship to the body and I felt I could invoke through that. I’d say that they’re an ongoing set – the images are part of a larger set of terms and tones that I’m piecing together before an exhibition.

LB It was interesting to see your work shown with an object maker, since your photography has been in a dialogue with sculpture for the past ten or fifteen years. But I feel your take on it is quite different. It’s not the photograph as object at all. It’s really a proposition.

DNS Because I can so easily indulge in the sculptural, or indulge in the painterly, I can abstract to a crazy extent, playing with lighting … and then I have to stop to remind myself what is the photographic moment. And that goes back to the journalistic mode, which maybe is the essence of photography and what we’ve been grappling with all of these years. In the way that I’m not interested in indexing an object that I made, or found, it’s about that object being pushed through the threshold of what photography is.

LB In the press release, there’s an interview between you and Brandon, and one of my favorite moments in the conversation is this kind of pairing you talk about between the ordinary moment and the potential moment.

DNS Which I think is when we talk about Eastern spirituality or object-oriented ontologies. It’s about this object that can be talismanic on some level. There’s this sort of spirituality to this idea that we’re here, now, in this body and we’re everything. But at the same time, I find that to be very closely related to experiencing trauma and how you’re in your body, and experiencing the feeling of being somewhere else completely. They’re two sides of the same coin. Part of me is dealing with certain political questions around how a body is identified and how you can change it. I’m interested in those narratives and those dialogues.

LB I was also really interested in your exchange with Brandon on found objects. It made me wonder about your relationship to the ready-made, and to Duchamp’s act as a kind of trauma – a shifting of categories or states of being.

DNS I started out with things that were much more recognisable. I was looking at the condition of the photograph within these objects, and I viewed photographs as being plagued by objecthood. But now, I don’t think that as much. The barriers between an object and a subject, they’re just shifting at times and it’s kind of difficult to pin down an object in that way. With the ready-made, it’s less about an object space and more about materiality in a cleaner sense – literally more about surface.

LB The flesh instead of the body?

DNS Exactly!

Liquid Isolation, 2019.

This conversation is from Objektiv #19. Objektiv is celebrating its tenth year in 2019, and this year's issues will look both backwards and forwards. For this issue, we've asked artists who have featured in our first eighteen issues to ‘pay it forward’, so to speak, and identify a younger artist working with photography or film whom they feel deserves a larger platform. Torbjørn Rødland pointed out artist DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN and chose Lucas Blalock from our editorial board to interview her.