FEDERICO CLAVARINO & BRIAN SHOLIS

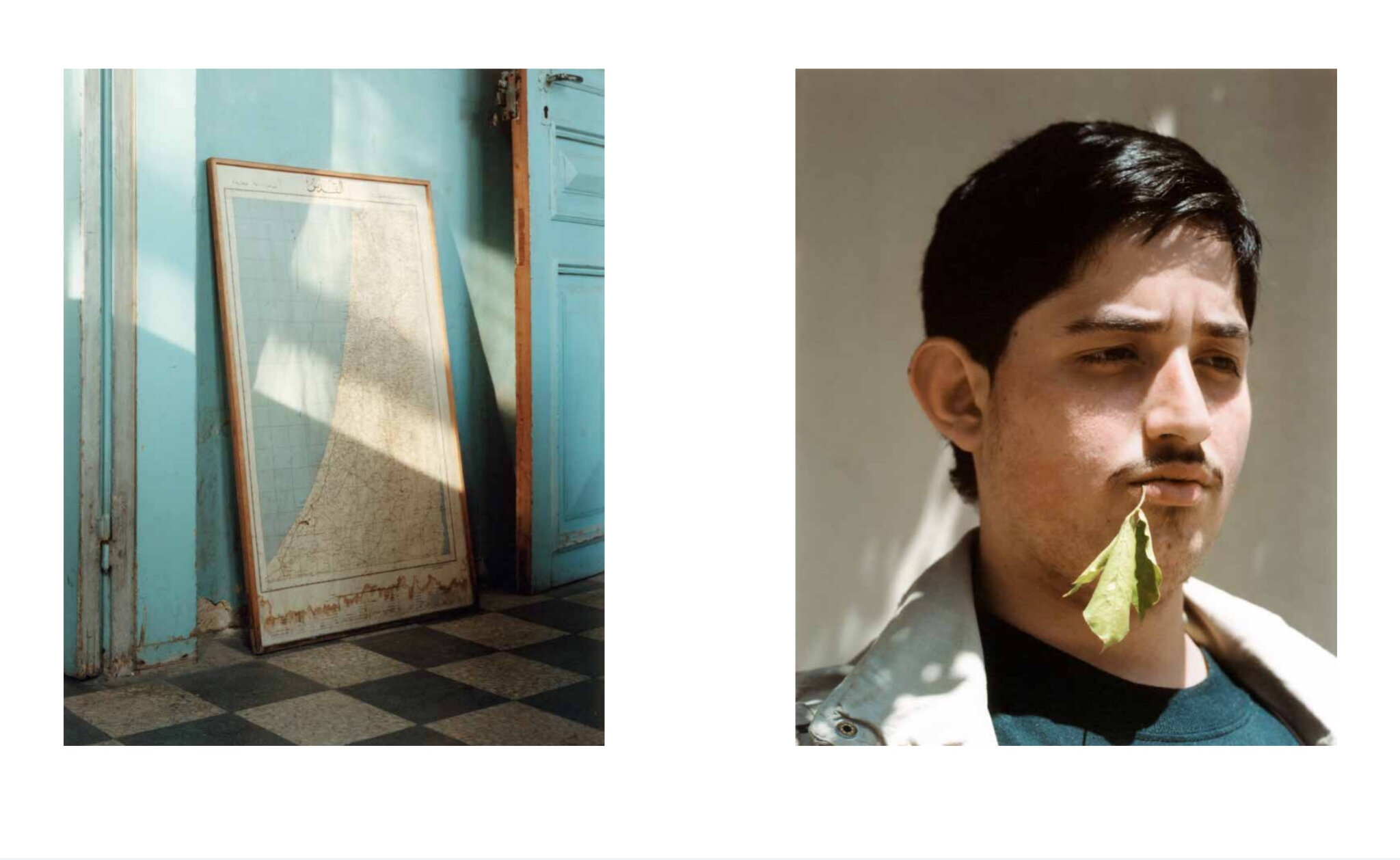

All images are from the book Hereafter, 2019.

WHAT WE FORGET MAKES US WHO WE ARE

A conversation between Federico Clavarino and Brian Sholis.

Brian Sholis I’d like to begin with the shift in your work between the pictures you made in Ukraine, circa 2010, to those in Italia o Italia. I see it as a move toward obliqueness or suggestiveness and slightly away from a conventional, narrative “documentary” style.

Federico Clavarino My Ukraine work came out of a need to try out things I admired in other photo-graphers—artists that brought me into photography, like Robert Frank. I wanted to travel and work in a way that moved between documentary and something more personal or lyrical. My documentary intention, so to speak, was eventually something I found frustrating in the Ukraine work. I didn’t know the country, couldn’t communicate in its languages, didn’t have enough time. These limitations urged me toward something a bit more personal. When the time came to confront my own country and I began returning to Italy, I had to find the fragile balance between what the work can say and what remains more silent or ambiguous. I could hint at things and outline possible interpretations. I was confident about a few of the ideas I wanted to express, and more emerged as I worked. What drove it all was an urgent sense of having to confront where I came from after a few years of not having lived there.

BJS What did leaving Italy and then returning reveal to you? Did that distance and perspective help?

FC Retrospectively, I’d probably say yes, it helped. I could notice things that are harder to see when you live in a culture. I was lucky, in a way. I was an insider who knew things tourists couldn’t know. The kind of things I couldn’t know when I went to the Ukraine. On the other hand, I had the privilege of the outsider. I could see both the shape and the texture of the place. When you live in an Italian city you’re proud of being surrounded by heritage and famous ruins—

BJS Western civilization.

FC Yes, exactly. You’ve been taught that should be celebrated. But it’s strangely similar to what Edward Said pointed out about Western understandings of Eastern cultures in Orientalism, that Westerners despised present Eastern societies while venerating their pasts. Many people look at countries like Italy, Spain, or even Portugal and Greece as the cradles of European civilization. And at the same time those societies can be deemed inferior compared to countries with different economic or political situations.

BJS You’re making this work around the time of the most recent economic downturn and the beginning of the Eurozone crisis …

FC It’s part of the same crisis. Anyway, I feel that in Italy one has a clear and stereotypical image of the past, one that inspires pride: beautiful ruins, Renaissance paintings, bountiful landscapes. But what about the present? Or the future? The present feels frustrating and ridiculous and it’s difficult to imagine a bright future.

BJS These disconnects seem to me like struggles for power over a narrative.

FC I think that’s true. Are we able to find a strong enough narrative for what we believe in, and does that help us assess the past correctly? If not, narratives we dislike might gain the upper hand. In a bleak way, my work also engages with that. As an Italian citizen, making that book had a sense of urgency. It was about finding meaning and a balance between the personal, the historical, and the political. That’s one reason why many things are doubled in the book. There is the “official” image of the country, which can seem like a simulation laid atop reality. But I don’t want my gestures, and the book, to be seen as ironic—which leads again to the more lyrical and poetic elements.

BJS You have described this book as your first mature work. Was there something about making sense of the past of the country you were raised in that gave you an opportunity to find, for lack of a better phrase, your photographic voice? Is there a connection between this subject matter and how you’ve learned to structure photographic narratives?

FC It is probably something I haven’t given enough thought to. On the other hand, my proximity to the subject matter, plus what I was going through as an immigrant, perhaps meant that I could be more effective. I had more emotional investment in that work than in anything I had done previously. On the other hand, in the beginning everything was very open-ended. I was just going back and walking around.

BJS In the beginning it wasn’t conceived as a project?

FC Not in the beginning; it was more a need. Things always start a little bit more like adventurthan projects. When you can give structure and purpose to what you feel as urgent or necessary, that’s when it becomes a project. One interesting thing about analogue photography is that it has a weird relationship with memory. It is retrospective: you only see things after some time. While you live things and shoot, you’re thinking. Then you develop the film, look at the photographs, and notice things you hadn’t previously seen. There are new connections between what you were thinking, what you saw, and what ended up in the photographs. The cycle then repeats, and each cycle is suffused with a little more intention. I am fascinated, in a long project, by the constant dialogue between research and practice. A lot of my ideas emerge from what appears in the film. The ideas get “developed” further by thinking and reading.

BJS Let’s tease that out while discussing The Castle, your subsequent book, which includes writing. Can you talk a little bit about your interest in theoretical research, historical discourse, even fiction and poetry? How do those things create the feedback loops you describe?

FC I spend a lot of time reading. The Castle is a direct reference to Kafka’s unfinished novel of the same name. Though the inspiration was not direct: I’d read The Castle years before, and the idea to work with it arrived perhaps halfway through the project. But even how I thought my pictures related to that book changed as I made progress. I was travelling around often for different reasons—

BJS Around Europe?

FC Yeah. I would take a lot of notes; I write a lot. Some is text, some is notes toward specific images. At other times I see something that connects to something else I thought or read, so I’d draw it and then try to tease out those connections later. There are goose-bump moments of connection, that’s when you feel you’re on to something. It’s a loose, associative process, but one I approach with rigor.

BJS On the subject of openness or looseness, can you talk about your preference for the photobook as a structure? Does it help you to give structure to what is otherwise a seemingly open, porous, and iterative process?

FC I think Marshall McLuhan said, “The more the world tends to break apart, the more desperately we try to put it together.” If your work is composed of bits and pieces and fragments, then you need to weave them together very well. The connections between them must seem inevitable. As you surf that kind of openness there is a kind of paranoia behind it, about how it will come together.

BJS In The Castle or more generally?

FC More generally. You’re not in full control, at least not until you have the intuition that it’s all linked together. Then you have to work on those links to make them intelligible. The closed format of the book helps muster a certain degree of both complexity and closure. I like working with books because you can read them the first time with the feeling that something connects it all—that paranoia again. You know you can’t get all of it, so you go back and read again. That’s the ideal.

BJS Is the particular structure of The Castle, in which each chapter concludes with notes, a microcosm of what you’re describing? Is it meant to encourage the reader to reconsider the photographic sequences she’s presented with?

FC Yes, and at the same time it provides context: you read those images in the context of those words. Our cultures privilege text. So, if you play it smartly, a text can broaden or redirect the reader’s understanding of images. It makes possible other interpretations. I want to invite people to go on the same kind of adventure I went on. Start here and you’re prompted to go elsewhere. I like the feeling that The Castle is not complete. It’s controlled, it’s finished, it’s a book—but it’s not complete in itself. You can profit from reading it more than once.

BJS Image and text create something like a parallax view that gives depth, a third dimension.

FC Exactly, something like a third dimension.

BJS Can you speak more about how The Castle uses different layouts, different pacing, in its chapters?

FC That, too, was the result of a long process. I remember one weekend I went to a friend’s country house. I went to the garage and spent a few days mapping out images on the wall. I really needed to see them all together, so I could map the images onto panels. Which is a bit like that Mnemosyne Atlas way of working, where you try to find and map connections in two dimensions.

BJS You mentioned paranoia earlier. It’s like the investigator in a police procedural trying to chart the sequence of crimes to discover who committed them.

FC Exactly! I love detective stories. I think the third season of True Detective has a lot to do with my work. There are many things you don’t know, you don’t notice. A crime scene can leave a lot unsaid. So, too, does photography. My projects are collections of evidence or fragments. I have to try to fill in some gaps—and encourage you to do the same. Only it’s not crime and murder, it’s history and ideas.

BJS I have never before made the connection between sequencing events to solve a crime and sequencing a photobook.

FC There are set ways to work with sequencing in a book, through spreads, or recurring elements, or narratives, or chapters. The interesting thing for me was trying to maintain that “third dimension” we were talking about. I think having different layouts helps. And the layering in the second chapter mimics those mosaics I worked on in the garage while editing. I kept making new discoveries, which helped to differentiate the chapters. I decided that the first chapter would work with super-imposition, in which one space is sandwiched onto the other. With the third chapter, I felt the need to have larger images, a different rhythm, a bit like techno music.

BJS It’s four-on-the-floor house music: every page has a big image. There is no respite. Let’s talk about Hereafter, your most recent project, and about switching from a 35-mm camera to a view camera. You’ve described your more recent formal evolution as being one in which the world gets cut into smaller and smaller pieces …

FC Hereafter was different because, first of all, it got really personal. Secondly, there was a specific story and there were other people involved.

BJS Did that story come out of the found images?

FC The story is the family story, so it is in the archive and in the conversations I quote from. Everything we’ve discussed about fragments and piecing together evidence confronted me when I encountered this archive—though it was really more of a mess. A chaotic mix of photographs, letters, clippings, drawings, and so on that I found in my grandmother’s place. Some of it I could make sense of, but a lot remains a mystery even to me. When talking with my grandmother and with others, some people remembered events others had forgotten. Some people remembered the same events differently. I was fascinated by the process of memory—how memory is made of forgetting. What we forget makes us who we are. Working with a view camera came from the fact that I needed to think the images a little bit more. I like the rituals the view camera invites: sitting down for a portrait, the long observation of an object in a still life. I enjoy setting up a tripod, waiting for the right light to come through a window, and how time and observation make some things disappear and other things appear. I had spent years running around and snapping away. So I sat down and talked and took notes and read letters.

BJS Perhaps this subject matter—patient family members, objects you own or have continual access to—allows you to pause in a way that your previous work, made on the move, could not.

FC Yes. I couldn’t afford to spend much time in the places I had previously travelled. Also, in this work, the role of the text is different. There are moments in Hereafter in which the way texts and images work together is accomplished and I’m happy with that.

BJS And is it those moments that you feel the story of your family opens out onto something broader, something universal?

FC Yes, but it is difficult to talk about without considering examples. In the beginning of the book my uncle Robin says that he doesn’t believe in death, that he has written something and that I will have to hear it. There is already an ambiguity: you’ve written something, why do I have to hear it? The related image is a door opening onto a room from which light streams out. There is this synaesthesia of hearing and looking and reading. The book has sound and voices, like a chorus. In another section, there is a portrait of a guy I met in Sudan, John. He had the same name as my grandfather. One day, while we were walking, I took a portrait of him. I wasn’t even sure I was going to use portraits in the book. It turned out he was squinting; it was like I was looking at him through the camera and he was looking back at me. I liked that in the context of a chapter in the book about the perception and representation of otherness. So, I decided to pair that portrait with a text, a report my grandfather wrote about a blue-eyed pickpocket in Sudan. This guy was convicted dozens of times because everybody recognized his blue eyes. At the end of the report, the pickpocket says, “all of this because of these accursed eyes of mine.” But, of course, he also uses his eyes to see—a complicated exchange is happening, all of which affects the portrait.

BJS His eyes were his identifying mark—a scarlet letter. How the world takes him in and what he uses to take in the world.

FC Exactly. And to think of all of this in the context of race and colonial history became very interesting. Nothing in these two fragments—the portrait and the report—speaks about this openly. But bringing them together invites peoples to think about that.

BJS Perhaps we can turn to work you admire that is not necessarily photographic. In the past you have cited WG Sebald and Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Both do a great job of balancing text and image in ways that are mutually reinforcing but also open them up.

FC The past and ghosts always appear in Sebald’s work. This is something I’m also obsessed with. But I also admire the way he uses pictures, that the photographs are not illustrations of what’s being said. In Chris Ware’s case, and in Building Stories in particular, I love that he creates a universe in which time is completely out of joint. You don’t know where to start reading. You can open the box and grab something at random, then piece the rest together depending on what you pick up next. I like that. I enjoy time travel when I can do it. We were talking about the book earlier. I would really like to try a project that does not end up as a book, that maybe allows for this kind of time travel. I like the idea of being able to work with something that can be kept open and revisited continuously.

This conversation is from Objektiv #19. Objektiv is celebrating its tenth year in 2019, and this year's issues will look both backwards and forwards. For this issue, we've asked artists who have featured in our first eighteen issues to ‘pay it forward’, so to speak, and identify a younger artist working with photography or film whom they feel deserves a larger platform.