FRIDA ORUPABO

Afterimage by Ruby Paloma:

I first saw Frida Orupabo’s work last year in Arthur Jafa’s exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Berlin. I have carried Frida’s Untitled (2018) with me since. I have been searching for a means to contribute to the nearly invisible topic of race in the visual art discourse in Norway and Frida’s work struck me at the exact right moment.

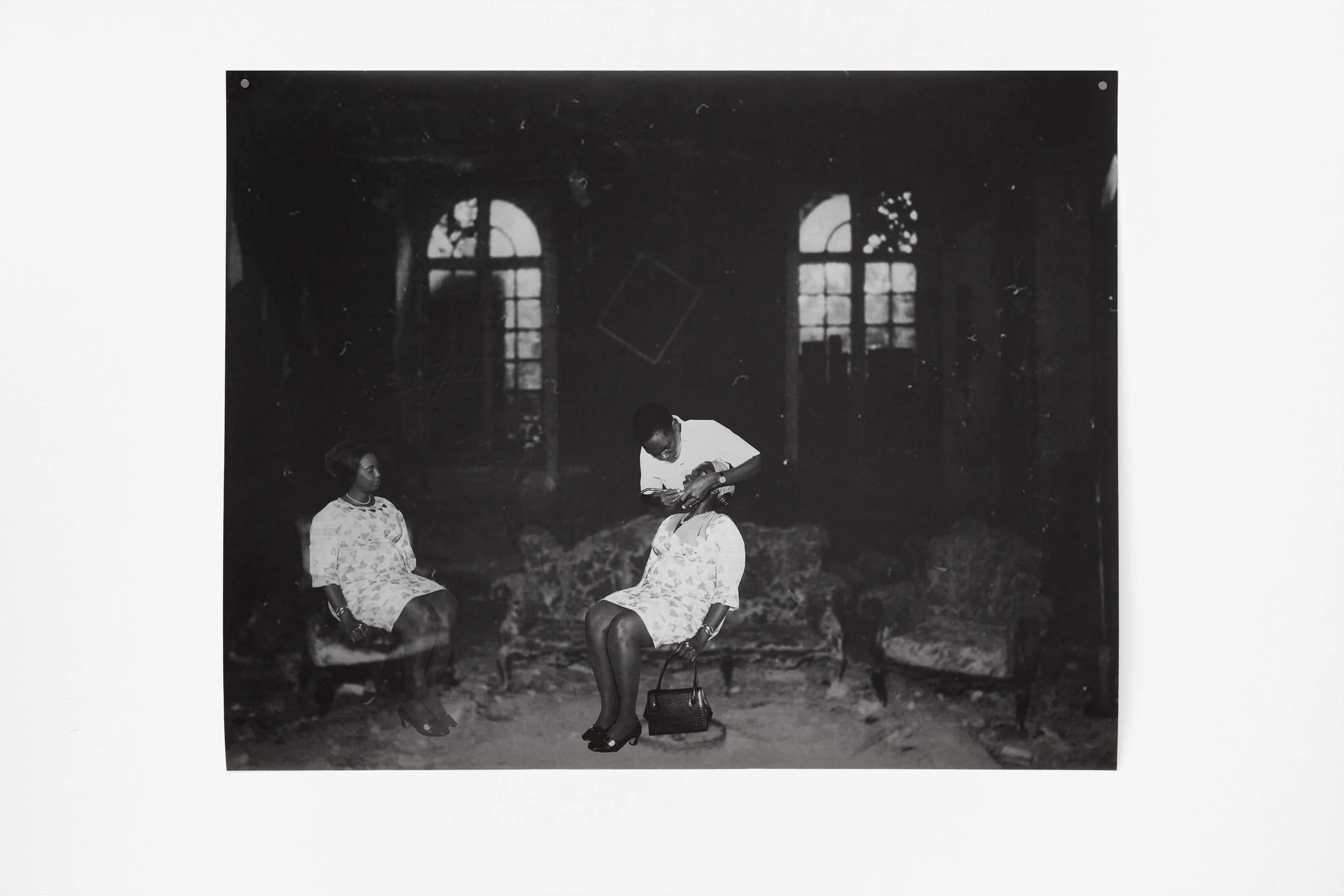

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2018, digital C-print, 89 x 105 cm, Courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake and the artist.

I don’t care for Instagram so I was relatively late to discover the work of @nemiepeba. I had no idea Frida was Norwegian, and that she lives about 300 metres away from me in Oslo. She is half Nigerian, like myself. I was stunned. Not because another Norwegian-Nigerian woman with a cultural agenda lived nearby, but because one of this country’s most significant contributors to Blackness in visual culture had been right under my nose for some time. I had never heard anyone talk about Frida, never seen her work included in a show nor seen her at an opening. It seemed that Frida’s almost unbelievable path to international fame had gone unnoticed to most in the Oslo art scene; Arthur Jafa’s crucial advocacy for Blackness, and use of Instagram, was in other words decisive for her breakthrough.

The role that a digital platform has played in disseminating Frida’s work (and her discovery) can be argued to be a democratisation of hierarchies in the art world, but it seems less relevant to me as @nemiepeba had little effect on the local audience, even more so because I first saw Frida’s work as enlarged collages; collage being the only thing I am certain about in the search for an expression for Blackness in Norway. Formally emerging from the philosophy of Dada artists and their distrust of rationalism and the order of civilisation, collage seems naturally suited to re-build social structures, comment on racial hierarchies, politics and culture, and display the complexity and nuances of a dispersed identity.

Frida’s digital collage of two black women and a black male dentist in a manor house combines WTO vintage photographs from Uganda (c.1970s) with Nona Limmen’s “Photogenic 18th century mansion captured on Polaroid”. For years, Frida has created an archive of images found online and used it as the basis for her digital and physical collages. She is interested in how we see things: race, sexuality, gender, family relations and motherhood, and by combining images that are not meant to be together, she challenges how we understand and talk about the arrangement of things. In Untitled it is unclear which bodies and actions belong where and when. Do black bodies (not) belong in (abandoned) mansions? Does the work of a black dentist belong there? The women are similarly dressed with identical shoes and bracelets and their dresses have the same pattern. How many times have I not been mistaken for someone with the same skin colour as myself?

The art of Frida Orupabo, both on and off Instagram, is of tremendous importance in promulgating Blackness in Norway. The lack of visible focus on the topic makes it seem like no one is working on it, making it harder to locate each other and start the discourse that will help build an identity around being brown or black in Norway today. Luckily, the Norwegian art institutions have now noticed her, and she is opening her first solo exhibition in Norway at Kunstnerens Hus on 1 March 2019.