ALIX MARIE

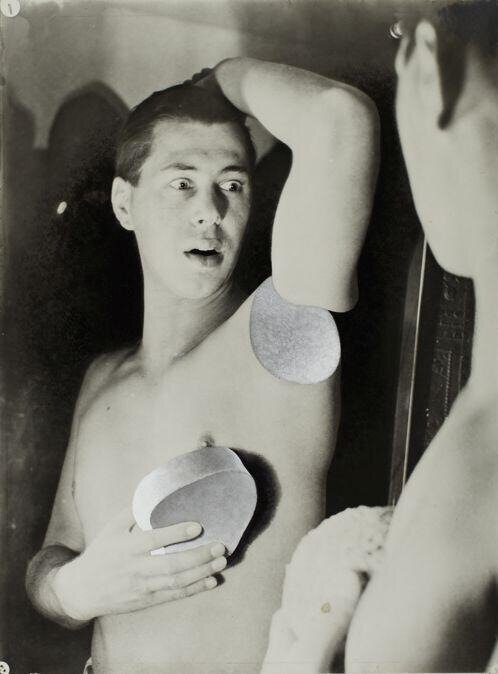

Philippe Halsman, French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. NYC, USA. 1949. © DACS / Comité Cocteau, Paris 2018. © Philippe Halsman | Magnum Photos

Perhaps because it was summer when I was asked by Objektiv to write about an image my choice has been influenced by the past. I was in France and had spent a lot of time sorting through hundreds of family photographs; postcards and memorabilia from various periods of my life. The two images that came to mind were Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) from 1932 and Philippe Halsman’s photo of the French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau from 1949. Bayer’s self portrait is an image I discovered as a teenager at the Bauhaus Museum on a school trip to Berlin. It has been in each of my bedrooms, in the form of a postcard or poster ever since. But then I felt that talking about it might actually kill the mystery of its power over me, so I’ll talk about Cocteau.

Halsman’s portrait returned to me as he has always been one of my heroes. Still today, as I am preparing my next show at Musée Des Beaux Arts Le Locle, I find images from La Belle et la Bête popping up in my head constantly. My family comes from cinema, and films are more influential in my practice than anything else, perhaps even more specifically the favourite ones from my childhood. Cinema is historically and socially a big part of French culture, Paris being the only city in the world where you have one cinema screen per hundred inhabitants. The average of going to the cinema is twice a month, it is very much part of our habits, and it’s something I miss here in the UK.

I remember as a child looking for through an encyclopaedia on cinema and for Cocteau they just wrote: génie à multiples facettes. I thought that was the most wonderful definition of an artist. This is exactly what the portrait depicts: Cocteau’s ability to write (poetry, plays, screenplays), set design, draw, paint and direct films. In a sense I think we can also read this portrait of an artist in a contemporary sense, as artists we are asked to have an incredible amounts of skills in order to survive: make good work, know how to write about it, know how to speak about it publicly, do your own PR through social media, know how to sell your work, teach...

Thinking of my practice which often mixes mythology and autobiography, and my passion for mythological antique sculptures, I think perhaps it originally came from Cocteau. As when he turns Lee Miller into an armless goddess in Blood Of A Poet for example. The transformation, if I remember correctly, was achieved by covering her in flour and plaster which must have been extremely uncomfortable. It is another aspect of Cocteau’s films which fascinates me: his DIY special effects which in themselves carry so much poetry. I think for example of when Jean Marais walks through the mirror in Orpheus for example, it is just cut and paste, instead of a mirror it is water when he goes through. This is something I try and keep in my practice; it comes from the everyday and the ordinary as I try to make and fabricate everything I can myself and often repurpose domestic objects. The manipulations in my work are physical, I never manipulate an image digitally. In the end these two images share a lot in common, they use analogue tricks to achieve a poetic and political portrait or self portrait of the artist, and they carry a reference to antique sculpture, all aspects which have fed my practice since very early on.

Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait), 1932.