GEOFFREY BATCHEN & ARE FLÅGAN

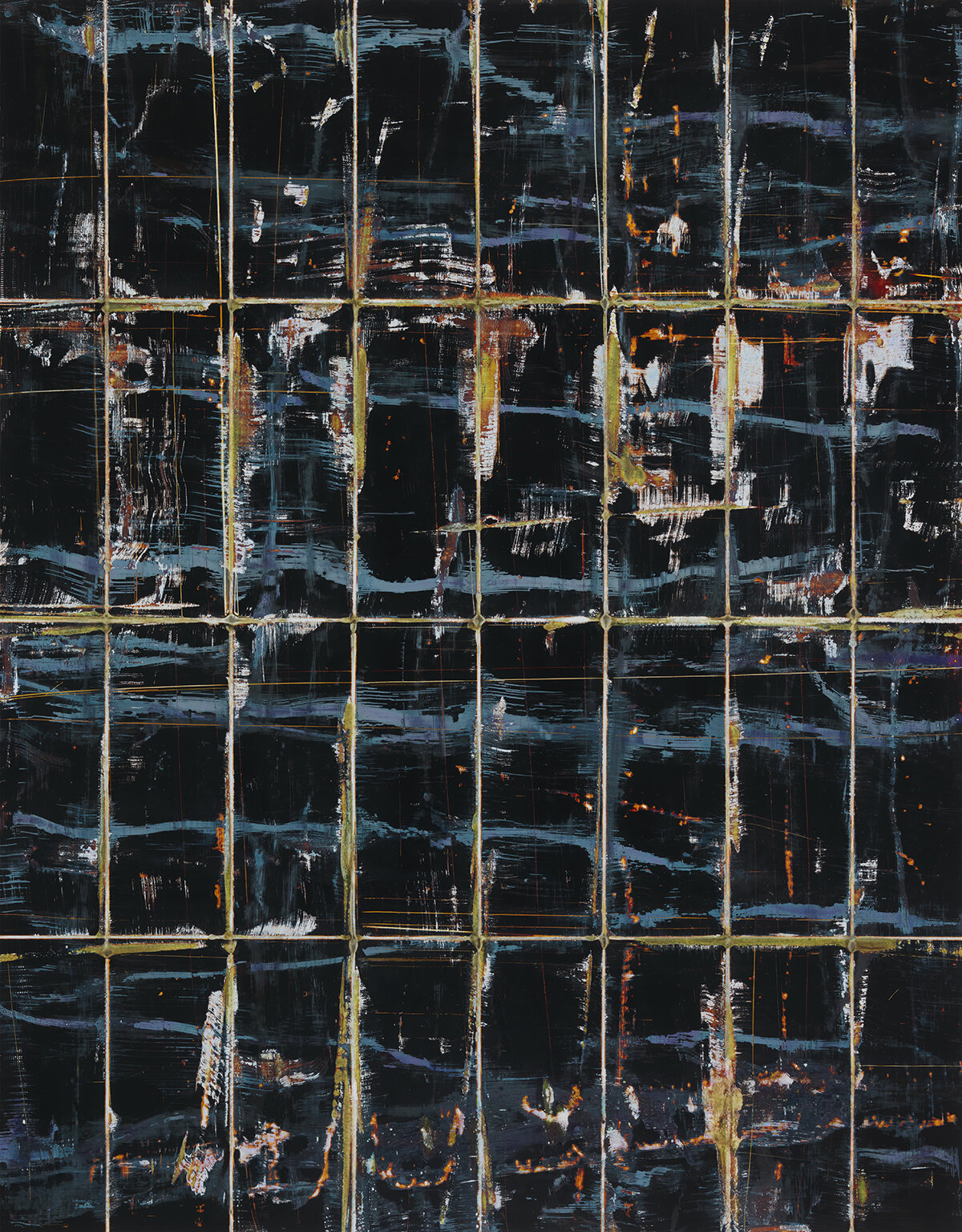

Shimpei Takeda, Trace #7, Nihonmatsu Castle, from Trace series, 2012.

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS

A conversation between Geoffrey Batchen and Are Flågan.

Are Flågan This issue of Objektiv posits a new role for, and understanding of, images. The motivation for opening up questions around this theme seems to be twofold: the increased primacy of the visual in our device- and app-driven social interactions, and the deeply encoded nature of digital images. When the platform Blogger was built in 1999, it was, at least by design, dedicated, serious and verbose. But since then, every popular milestone in the evolving social media scene has truncated texts and made room for images. Today, users on Facebook alone upload on average 136,000 images per minute. Twitter limited chatter to a maximum 140 characters in 2006, and Tumblr introduced microblogging in 2007. From 2010 onwards, Instagram filtered out words in favour of networked photographs. A year later, Snapchat offered to share a snapshot with the option of an emoji instead of a caption. You’ve recently been writing about this exponentially growing imagescape of pictogram and selfie communications. Do you see a space for reformed literacy in these fleeting, technological exchanges, or do we experience both an impoverishment of words and an inflationary devaluation of photographs?

Geoffrey Batchen The figures you cite seem overwhelming – so overwhelming that one feels helpless in the face of them, stripped of the ability to respond. Joan Fontcuberta has described the contemporary situation as “photography’s revenge”. Certainly, it seems at first glance as if it will be impossible to write a history for this imagescape or to engage it in a measured and critical way. But in fact photography’s numbers have always been overwhelming. Billions of digital images are no more debilitating to one’s critical faculties than the millions of analogue photographs that used to be churned out each year during the second half of the twentieth century, or, for that matter, than the forty daguerreotypes per day produced by Richard Beard’s London studio in 1841. In each case, an individual observer only encounters a tiny fraction of these photographs, usually just enough to recognise that both personal and commercial photography have always been driven by an economy of repetition and sameness – if you’ve seen a handful, you’ve seen them all, more or less. This allows the possibility of some critical purchase on particular genres of photograph. After all, Roland Barthes attempted to deduce the essence of photography from his examination of just one (unreproduced) personal photograph in Camera Lucida. A number of artists have produced interesting work that allows a similar reflection on our contemporary imagescape, including Fontcuberta, Joachim Schmid, Erik Kessels and Penelope Umbrico. They give me hope that critical thinking is still possible within and about this image environment. What the phenomenon you describe does demand is an analysis of the global media economy that drives it, from the manufacture of cell-phone cameras to the corporate exploitation of social-media sites of all kinds. This is the kind of analysis that now needs to be undertaken by professional scholars. However, your question seems to bear more on the experience of individual users of social-media sites. Some have worried that people once had some measure of “social literacy” in relation to their family snapshots, but no longer do. I’m not convinced that this is the case. In my experience, many users of Facebook, to take but one example, have a quite sophisticated grasp of its potential, as a means of social exchange and even as a creative medium. They recognise that personal photographs are indeed mere nodal points for social exchange, rather than pensive moments or immortal documents. Were snapshots ever treated as such documents? Perhaps sometimes, but I suspect usually not. They’ve always been rather ephemeral objects, faithfully (if selectively) stored but seldom consulted. Of course, social-media sites are not good storage depositories. They claim ownership of whatever images are uploaded onto the site. More importantly, these sites will no doubt at some point become obsolescent; when they go, so do the personal image archives of their users. Where will historians look to study the snapshots of the early twenty-first century? Getting back to your question, I wonder if the fears of impoverishment and devaluation that some have expressed are driven by a nostalgia for a time of self-awareness and literacy that in fact never really existed. Perhaps what we should be asking instead is “what new kinds of literacy are being generated and encouraged by social media?” and “how are both photography and its users being reshaped by this new kind of literacy?” Having said all that, I wouldn’t want to pretend that nothing has changed. My parents used to write long letters (by hand) to their parents every week. I write only emails, and my handwriting has atrophied, but I can now exchange messages with a global audience (including with you), transforming my place in the wider world. My children may, as you suggest, substitute a prepackaged icon for a written message. Nevertheless, they’re voracious readers as well as frequent users of new media (they make little movies and send them to Grandma). In other words, they’re able to do things that I could never do, and their skill sets are different from the ones I was taught to have. So my inclination is to assess any changes in terms of difference rather than just as signs of loss and impoverishment.

AF Indeed, but what we’re also seeing is the acceleration of production. It speaks not only of a sheer upturn in volume, but also the relentless velocity, the expected frequency, at which this photographic pulse must pound for our social accounts to be considered present and alive. Those logged in must continuously record to stay relevant and vital. Speed has thus come to dominate and relegate all that is slower to the margins. The question here is if the incredible momentum and persistence at which imaging now operates also fundamentally changes our understanding of and relationship to photography in general. Astoundingly, the total count of calotypes ever produced since their invention by Talbot is surpassed by the number of captures Snapchat and its siblings make public each and every nanosecond. Photography’s contemporary revenge, which you cite, consequently rests not only with these locust-like swarms of images devouring time and space with insatiable appetite, but with its compulsive yet tyrannical insistence on spawning and discarding new moments of passing. Photography has become more of a slight buffering of the present and omnivorous moment than an archival pointer to the human condition. Edward Tufte, author of The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, is reported to purposefully delete almost every photograph he ever takes. His double acts of euthanasia deny both him and his photographs the eternal permanence they, in every sense, seek to overwhelm us with. This fatal strategy for photography is echoed by the Snapchat application, where ephemeral images (almost 9,000 flickering per second at present) live for a mere 10 seconds before disappearing forever. While privacy issues may misguidedly have attracted many users initially, this popular photographic apparatus continues to seize the zeitgeist of images by forcefully erasing the plurality of ‘that-has-been’ and with it, to stay with your favorite sources, a desire for what Roland Barthes has called, by reduction, the essence of photography. Are we currently inscribing another way of seeing and being in images that shifts the conception of photography?

Lynn Cazabon, Diluvian (detail), 2010–13, 40 silver gelatin solar photographs.

GB The being of photography has constantly been in flux, at the beginning and ever since. Nevertheless it seems that the desire to photograph has remained a constant element of the medium, motivating its inventors and their many successors to produce an infinity of photographic pictures. Already, then, I’m seeking to complicate your question a little, if only by shifting its focus from the fate of the pictures to the act of their making. If we follow your suggestion and stay with Barthes, it might be argued that we take photographs in order to ameliorate the very “catastrophe of death” that photography, by testifying to the passing of time between then and now, and thereby to our own inevitable passing at some future moment, constantly reiterates. The act of photographing is therefore a contradictory one, always flickering uncertainly between an affirmation of life and a certification of death. This helps explain why so many photographs (the vast majority in fact) are banal and ephemeral. How they are doesn’t mat- ter; all that matters is that they are, that photography happened. The ‘that-has-been’ is that something was photographed. In that sense, it also doesn’t really matter if the resulting photographs last for only ten seconds or for fifty years. As with Mr Tufte, what’s important for most people is that a photograph was taken, that a gesture was made to momentarily still both life and death. A photograph is but the ghostly remains of that futile act of suspension, of that yearning for immortality. In an otherwise secular age, taking photographs is, I am proposing, the last bastion of a theological faith in the possibility of an afterlife. This is surely the principal narrative of Barthes’s Camera Lucida, composed, of course, as an act of mourning for his deceased mother. His narrative is built around another of these oscillations, from the “essential” but absent photograph of that mother to the presence of every reader’s own missing loved one, projected into that beckoning, empty space in the text. Designed to be experienced like a photograph, the book’s central motif is a flickering back and forth between absence and presence, between zero and infinity. Published before the digital age, Camera Lucida nevertheless offers a model of how the overwhelming torrent of electronic images might be corralled and engaged. But your question is about speed rather than volume. The inference is that an increase in photography’s velocity, in the velocity of its distribution and exchange, and an associated decrease in our attention to the photographic image, might amount to an ontological shift in photography’s being, or at least in our conception of the medium (is there a difference?). But I wonder, again, if we’re talking here about matters of degree rather than of substance? Modernity (of which photography is the very embodiment) has always been associated with the acceleration of everyday life, with the “annihilation of both space and time” as nineteenth-century commentators liked to say. In any case, speed is a relative experience. Today, for example, we’re impatient if a download takes more than a second, forgetting that not so long ago it might have taken hours. I remain to be convinced that this shift makes that much of a difference to our conception of the thing being downloaded. Or that our emotional investment in the photograph has significantly changed as a result of the transition from analogue to digital technologies.

AF Your point that our investment in the photograph survives transitions, and stands the test of time, points in my mind to its core indexicality. An index, just to revisit Charles Sanders Peirce’s notion of trichotomy, is a sign linked to its object by an actual connection or real relation. This is the essential characteristic of what we’ve come to identify with photography, and how or where a photograph is made to appear is thus subordinate to an enduring recognition of what it represents. The parenthetical question you pose, about the difference between photography’s conception and ontology, is thus an inescapable one that has remained vital from your first book, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography, to your latest, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph. The elementary experiments with light and sensitised paper common to both titles share an intertwined origin and lineage; the former conjuring an intricate conception and the latter an investigative ontology of photography. It’s certainly interesting that while we’re generally trawling the vast cybernetic networks of radiant images to spin origin stories for the medium, you’ve chosen to focus on a history of primitive prints close to its simplest and purest form. Could you describe what you see in these cameraless photographs that motivated you to highlight their shadowy existence?

GB As William Henry Fox Talbot signalled in his first comments on photography, the medium he helped invent is peculiar for handing over its representational capacity to whatever is being represented. And this generosity is especially foregrounded in cameraless photographs. The things we see in such photographs seem to have imprinted themselves on the paper before us: directly, physically, causally, without mediation, at one-to-one scale. For this reason, to make a photograph without a camera is, as you suggest, to privilege photography’s indexical capacities over all others. And this gives such photographs a powerful attraction. As Peirce suggested, indices “direct attention to their objects by blind compulsion”. In his terms, cameraless photographs establish a “real connection”, first between an image and its referent, but then between the image and its observer. Operating by contiguity, both materially and psychologically, a photograph made without a camera promises to get us closer to the presence of things, closer to presence in general. It promises, in other words, to fulfill a desire that lurks within all acts of representation: to collapse the boundary between absence and presence, between an image and what it’s of, between that image and its process of production. In skillful hands, photographs made by direct contact with the world can therefore convey things in ways other photographs cannot, because they allow that world to speak for itself as itself. As a consequence, pictures made without a camera can be grounded in the real world or let loose to create a visual experience peculiar to themselves. Since the 1960s, many contemporary artists have sought to avail themselves of, even to exploit, this dual capacity. In so doing, they necessarily inherit and reflect on photography’s own modernist heritage. Indeed, a kind of retromodernism is a common characteristic of contemporary cameraless photography, sometimes turned to ironic effect and sometimes called on as part of an effort to retrieve the critical capacities of a bygone era, when art-making still seemed to have a tenacious purchase on political and social life. And the abandonment of the camera has also allowed artists to experiment with the photographic medium itself, complicating both its identity and its creative potential. Given our contemporary context, artists making cameraless photographs today assume that the photographic medium is and has always been a politically charged field; to engage the visual and chemical grammar of the photograph is to dispute and challenge that politics at a very basic level. Apart from anything else, to make such photographs returns photography to a unique, hand-made craft and away from an automatic subservience to global capitalism and its vast economies of mass production and exploitation. Not that this kind of work isn’t capable of engaging with important aspects of those economies. On the contrary, in offering us the tactile other to the evanescent digital image, contemporary makers of cameraless photographs make art that’s all about the digital age. By slowing down the photographic act, these photographs also slow down our perception of this act; they ask us to pause a moment and think critically about the consequences of our post-industrial information economy. But throughout photography’s history the cameraless photograph has always been a subversive element, an auto-critique of everything that photography is supposed to represent. For, in rejecting the camera, such photographs also reject humanist perspective, rationalised space, three-dimensional illusion, documentary truth, temporal fixity, and so on. All these characteristics make these kinds of photographs worthy of a close study. In my case, I’ve written a history of the cameraless photograph in the book Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, published by Prestel this April, and have curated an exhibition on the same theme, which opened at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth in New Zealand the same month.

Marco Breuer, Untitled (C-1378), 2013, Chromogenic paper, folded, burned, and scraped.

AF Although collectively billed as photographs, the cameraless works included in your book and exhibition seem to be separable into at least two categories: there are the contact prints intimately connected to the photographic tradition, but also superficially abstract images relying on contextual information to be seen and recognised, to make sense, beyond an aesthetic appreciation of them as seductive objects. These images are often made by exposing the photographic sensitivity, or an intermediary negative substrate, to other forms of radiation or weathering environments for extended periods of time. The resulting patina is arguably another type of time capsule: a recorded and condensed span rather than a singular instant caught by brief physical contact or, more conventionally, the blink of a shutter. Since these particular emanations plot every influence that led to and defined their appearance with an aggregate density, I would suggest that the prolonged exposure is a form of data-harvesting and the resulting shadows cast on sensitive paper mirror an infograph. What finally develops is the visual display of obscure, until contextually tagged, traces logged along a collapsing axis of time, the illuminating graph of a dimensional dataset. The brief for this issue of Objektiv looked for epistemic changes in our understanding of images among the latest digital trends, and singled out a broader conveyance of encoded information, part and parcel of the sharing economy, as a possible ontological leap for the myriad members of the photographic medium. While these transformative actions appear to bring a new reality to life, the recognisable features of the image itself, kept intact by the formal demands of formats, essentially remain animated by previous investments in photography. Your recent history, however, actually introduces intriguing photographs that come across as vessels of graphical information. How can we interpret their significance?

GB I’ve already tried to suggest some of the broad ways in which their significance might be assessed. But let me describe a few recent examples in more detail, each of them slightly different in approach. Consider, for example, a work made by American artist Lynn Cazabon between 2010 and 2013. Titled Diluvian, it comprises a grid of unique contact prints, with their imagery and the means of its production both being directly generated by the work’s subject matter. Embedded in a simulated waste dump, and therefore covered with discarded cell phones and computer parts as well as organic material, expired sheets of gelatin silver paper were sprayed with baking soda, vinegar and water, sandwiched under a heavy sheet of glass, and left in direct sunlight for up to six hours, four prints at a time. The chemical reactions that ensued left visual traces – initially vividly coloured and then gradually fading when fixed – of our society’s flood of toxic consumer items, produced by the decomposing after-effects of those very items. Other work has a more specific context. The potential consequences of the uncontrolled release of atomic radiation were highlighted after the earth- quake and tsunami that swept the east coast of Japan in 2011, and the subsequent meltdowns at three nuclear reactors. Seeking to make visible this otherwise invisible threat to his country’s inhabitants, Shimpei Takeda collected contaminated soil samples from twelve locations throughout Japan, each of them of historical and symbolic significance (“with a strong memory of life and death”, as the artist puts it), and then placed the samples on sheets of photo-sensitive film for a month. About half the resulting images remained almost black, but some were soon speckled with a blizzard of radioactive emissions, abstractions that nevertheless indelibly recorded the fragile state of the Japanese ecology. A distinctive feature of cameraless photography is its ability to capture a diverse range of temporal experiences, from lengthy durations to fractions of a second, in both cases allowing the representation of phenomena otherwise beyond the capacity of the human eye to see. The New Zealand photographer Joyce Campbell, for example, decided to conduct a microbial survey of Los Angeles, a city in which she lives for part of each year. Accordingly, in 2002 she swabbed the surfaces of plants and soil from twenty-seven locations chosen out of her Thomas Guide to the city. She then transferred each sample onto a sterilised Plexiglas plate of agar and allowed it to grow as a living culture. The cibachrome positive colour contact prints she subsequently made from these plates resemble abstract paintings and yet also offer a critical mapping of the relative fertility of this particular urban landscape, so dependent on the politics of water distribution. As Campbell has said, “There seemed to be a kind of poetic reversal in picturing the most botanically manicured parts of the city as oceans of bacteria and fungi, while revealing the relative sterility of the water-deprived south and east.” These examples refer inwards to their own coming into being but also outward to the material worlds they signify and beyond that to the environmental degradation of our planet. The work of German-born, US- based artist Marco Breuer inhabits a more hermetic social space. Nevertheless, it still manages to confront us with a robust physicality, both in its materiality as a series of photographic objects and by way of the various erosive treatments to which these objects have been subjected. By folding, scoring, burning, scouring, abrading, and/or striking his pieces of photographic paper, Breuer coaxes a wide range of colours, markings and textures from his chosen material. His are photographs that actively involve the body of the artist in their making. They’re about nothing but contiguity in the raw. Both touched and tactile, Breuer’s photographs have themselves become surrogate bodies, demonstrating the same fragility and subtractive relationship to violence as any other organism. And like any other body, they also bear the marks of time, not of a single instant from the past, like most photographs, but rather of a duration of actions that’s left accumulated scars. These are now witnessed, in a perpetual present, by the body of an observer suddenly made aware of its own inherent vulnerability. As I said, each of these examples is informed by its own specific contexts of production and reception. And each, as you suggest, appears at first to be composed of abstractions, requiring some sort of textual accompaniment to signify in any politically meaningful way (a charge, by the way, that could be levelled at most challenging art work, of whatever style). However, it could be equally argued that such work exhibits sufficient visual interest to induce a viewer to inquire a little further, to pause and think, or at least to enjoy a momentary immersion in a quite singular ocular experience. That experience is provided by marks and traces left by the direct action of the world on a photographic surface, making this very much an art of the real and nothing to do with abstraction at all. In an age of endless electronic mediations (including by camera-made photographs), there’s something refreshing, bracing even, about art objects that allow the world to speak for itself, as itself, with an absolute minimum of such mediation.

Joyce Campbell, Griffith Park, 2002, from the series LA Bloom.

AF This exchange has been an enlightening return to the fundamental matters of photography. Through my work in the field of imaging, I’ve grown dependent on the mathematical formulas of signal processing and the wave patterns of frequencies to comprehend the medium. This fluid digital realm operates in stark contrast to the molecular structures of particles, negative and positive, evoked by chemistry in the analogue works discussed above. Upon reflection, it seems almost unfathomable that essentially the same photograph can develop from the opto-electronic conversion function and the transformation of sil- ver halides to metallic silver. The respective wave and particle signatures of these technologies are also observable in the behavioral duality of light itself, so photography today quite appropriately surfaces both from and as all these maddening yet alluring presences of a strangely paradoxical nature. Finally, how would you, as someone who has shaped our collective interest in and understanding of the medium through your many exhibitions, books and articles, describe your continued fascination with photography?

GB This word ‘fascination’ implies an attraction to photography of a sort that only occurs under the spell of an enchantment. That’s not necessarily a false association; as I’ve already suggested, photographs suspend us between life and death, appealing to our most elemental anxieties. I’m no more immune to these anxieties than anyone else. However, I’ve also always been drawn to photography’s ubiquity. It’s everywhere. And that means the study of photography licenses me to talk about almost anything, from sex to war, and from microbes to planets. Moreover, as commentators of the calibre of Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes have already noted, this is a medium that seems to embody all the contradictions of modernity itself (including its latest, global, data-driven phase). To engage a history of the photograph is to confront the political economy of modern life itself, and that seems to lead one well beyond the precious confines of the art world. All these aspects of photography continue to hold an appeal for me, and I suspect, for many others too.

We wanted the first book from our Objektiv Press-series to consist of twelve conversations from previous issues and to be launched during this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles. Due to the current situation we will focus instead on our two upcoming essay publications and share (and republish) the dialogues online. This conversation is from Objektiv #13, The Flexible Image.