B.INGRID OLSON & LUCAS BLALOCK

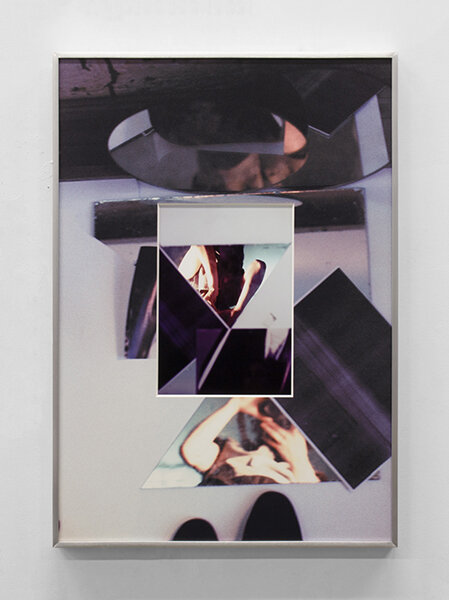

B. Ingrid Olson, axiomatic, fingered and bent, 2014. All images are from the show double-ended arrow by B. Ingrid Olson at Simone Subal, 2015.

A conversation between B. Ingrid Olson and Lucas Blalock

Lucas Blalock In the photographic works in your show double-ended arrow at Simone Subal in New York, ‘the body’, in this case your body, played a central role. Can you talk about the relationships you’re drawing between the body, the camera and the photograph?

B. Ingrid Olson The body and the photograph are both means to address the dynamic of ‘subject’ and ‘object’, specifically the jump between an interior, direct experience and an exterior, pictured existence. Because I hold the camera pressed up to my face, the perspective within the images is primarily subjective, as seen through my eyes. As I’m taking the photographs, I simultaneously insert various parts of my body in front of the lens (my hand, my legs, my torso, my feet), which reinforces the camera’s location as a stand-in for my vision. Alternately, there are instances when the viewpoint shifts to capture my body’s reflection in a mirror, making me also the subject, the figure, or focal point of the images. In addition to my body’s placement within the images, the ideas of subject and object are related to the way in which the physical photographic prints are layered into and onto one another. The collaged superimposition of multi- ple printed photographs hinders the composition’s ability to become a single, continuous image. When your eye hits the edge of one image to find the edge of another image, there’s a kind of push-back, creating an awareness of looking rather than seeing. This very denial of immersion in the image, by way of the actual objectification of the photograph (the highlighting of the photographic print as a physical, material thing), repositions the images, which depict my body and my perspective, within the realm of the object and the ‘exterior’ for the viewer, even though the individual images may picture the opposite. In this situation, the viewer is invited to share my eyes, even to enter into my body to see what I see, but then the photographic constructions – as reflexive objects – don’t allow this, denying entry, even forcibly kicking the viewer out.

B. Ingrid Olson, the fountain containing itself, virtual fold, 2014.

LB I really like this tension you’re speaking of between the embodied object, the body proper, and the photograph. I’m curious to know whether you started with photography and its limits to arrive at this place, or whether you came to it another way.

BIO I have a background in drawing, which continues to influence the way I think about making images. However, the particularities of the photographic process have been the primary force in shaping my recent work. A kind of warmth, touch, imagination and revision are implicated in the act of drawing, to which photography has provided a degree of distance, a quickened speed and a static sensibility to fight against.

LB I’m really interested in photography as a static sensibility that can be approached as a problem in its own right. It reminds me of something Deleuze wrote about painting: that it’s a misnomer that the painter starts with a blank canvas and that in actuality the starting point is already crowded in by all of the previous gestures and clichés that make up painting’s history. There’s a way in which this can be applied very straightforwardly to photography’s history as well, but I think turning it into a question of how we understand photographic pictures to ‘act’ is more exciting.

B. Ingrid Olson, sand the walls, rip the floors, 2014.

BIO A precedent can be overcome by invention or even a slight modification. Gerhard Richter wrote this in an introduction to a book that I’m reading right now: ‘The classic photograph invents in that it records an already existing presence while at the same time causing this other or this otherness to be there in the object world as a form of production, performance, and manipulation.’ Do you think the ability of the photographic image to ‘act’ is an extension of this kind of invention or otherness?

LB Yes, I think I do. Kaja Silverman talks about this through analogy – a photograph being of a specific type of analogy that cannot be separated from the thing analogised or pictured. I do wonder what Richter means by ‘classic’! I want to try and do a better job of answering your question though. I like the sense in Richter’s quote that the photograph is adding a term and a thing to the world; a thing with relationships to other things, but also a thing that can’t be reduced to a representation of something else. I think it’s Craig Owens who talks about how the relationships in a photograph are actually invented by and only exist within the photograph. What I was really trying to get at when I brought up this idea of ‘acting’ was the sense that photograph is highly legible and at the same time very plastic. The viewer brings a lot to it and for me this has set up a situation where play becomes very available. What kind of activity is out of bounds in this contract with the viewer? And why? What isn’t but seems like it should be? I feel as if your work is taking up this play. Is it a fair way to talk about it?

BIO I don’t think of anything as being necessarily out of bounds to the viewer, as I don’t see their viewership as a fixed contract. My biggest concern in regards to the viewer is deciding what information to make available and what to purposefully occlude. The meaning of an artwork, like a sentence, can change entirely by adding one thing and subtracting another. Though I avoid the term ‘narrative’, there are obviously elements that take the work beyond pure information and beyond process. The photographs are specified by each plastic decision made, but in the end, my primary focus – in relationship to communication – is leaving room for inference and interpretation. Mis-reading, crude understandings, tangents and inconclusive ideas are all part of a seed or spark for new thought. I hope that some elements in my work will allow for this energy in the viewers. I don’t consider my work inconclusive or totally open, but I am hoping the works can evoke something like an ellipsis, or a statement that almost turns into a question.

LB I like this distinction you made earlier between ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’, which could be said to be the point at which a photograph’s pictorial qualities begin to overwhelm its informational ones. These works continue this pictorial activity through a number of extra-photographic framing mechanisms – the mat boards, inlays, etc. Can you talk about how the logic of the pictures is continued through these devices? I’m really curious whether, for you, the weight of them is located more within the (albeit accentuated) photographic space or if the work is the manufacture of an object that’s part photograph.

BIO Rather than giving emphasis to the photograph over the constructed object or vice versa, for me, it’s a matter of how both come together to create a hybrid space. I think a lot about the ‘aside’ in writing, moments in which an author breaks the fourth wall, addressing the reader directly, or when a footnote is used to expand on a facet of an idea, as a visibly separate explication or a tangent alongside the primary text. These stylistic and formal structures are related to the material aberrations in my work: the inset, mounted and stacked photographs. They exist as an ancillary pull away from the centre, a secondary element that expands the context and the content of the work.

LB I want to change stream a little, because as much as I can see all the concerns you’re describing in the works, when I think back to walking into the show, my own entry point was less formal. I immediately started thinking about feminist practice of a generation or two back, about the body and its relationship to technology/ies, and about the usefulness of the body as a stake with which to interrogate those relationships. It’s an awkwardly forward question, but are you thinking about these things? Is there a set of personal or political impulses that you start from?

B. Ingrid Olson, errection of a plate of glass between, 2014.

BIO I’m interested in qualities of femaleness versus maleness, often symbolically, like stereotypes of material or elemental and energetic associations – a straight line versus a curve, hard metal versus soft fabric, or even a brash personality versus an apologetic one. And I understand the potential of my gender to code or shape how the bodily aspects of my work are received and interpreted. I can appear platonic in one situation and invitingly sexualised in another. When my body is doing one thing, it’s at the same time not doing another thing. Images of my body bear traces of choice: clothed or naked, closed or open, vertical or flat. Of course, in some cases, I’m consciously thinking about the potential for gendered readings, while at other times, when the work is more process-oriented, structural or personally associative, the fact of my being a woman can be more automatic or default, not highlighted or underscored. I’m still coming to terms with the potential power, and also the pitfalls, of imaging my own body as a female body taking a stance.

LB All these binaries make me think of Jeff Wall’s ‘Photography and Liquid Intelligence’ essay. In a lot of recent photographic practice, process itself has been the flow crystallised in the photograph. But I feel really strongly that these works of yours aren’t functioning in the weightless combinatorial economy of images. Instead, they’re grounded in the body and that they draw a lot of power from that insistence.

Do you feel as if your pictures relate to ‘selfie culture’ or a ‘culture of images’ more generally? Or more to drawings and paintings? Or scrapbooks? I have the sense that the compilation of decisions in these later formats are categorically different from the former, but I also have the suspicion that someone like the artist Helen Marten might disagree with me.

BIO I agree with you that the work is grounded in the body – not only my body in the images but, I hope, in the viewers’ bodies as well. I want viewers to consider the work and their relationship to it as they approach it, as they stand in front of it, and again as they leave it. This seems more related to painting or sculpture – moving in the space around an artwork, considering it from far away and up close, inspecting its sides and its surface – than to the endless scroll of selfie culture. I’d say my work relates to selfie culture about as much as anything that incorporates self-portraiture does. But, I don’t think that’s very interesting.

If I were to think through Wall’s essay, then perhaps, in my own work, the body can be a kind of substitute for this ‘liquid intelligence’. A representation of a person can hold similar symbolic weight to a flow of liquid as something irreducible, erratic and changeable that exists in a kind of opposition to – but is also complemented by – the rigid mechanism of the camera. However, I don’t consider any subject or process in my work to be crystallised or finished through photography, regardless of the specificity of the pictorial or manufactured elements.

B. Ingrid Olson, three rectangles by three rectangles, infinite sheet, 2014.

We wanted the first book from our Objektiv Press-series to consist of twelve conversations from previous issues and to be launched during this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles. Due to the current situation we will focus instead on our two upcoming essay publications and share (and republish) the dialogues online. This conversation is from Objektiv #12.