CATHERINE TAYLOR & NICHOLAS MUELLNER

Picture taken from Image Text Ithaca’s website.

MAKING BRIDGES

A conversation with Catherine Taylor and Nicholas Muellner on The Image Text Ithaca initiative.

Nina Strand As you know, we’re working on a double issue named The Flexible Image this year (2016). The Ithaca College Image Text MFA is a unique degree program focused on the intersection of writing and photography. Our board member Lucas Blalock told me about your programme, a programme that feels like something that’s been missing for so long. Could you tell us about how this began?

Nicholas Muellner It began as a casual conversation between the two of us. Coming from photography as I do, but also using language a lot in my work, I’ve felt a bit displaced by the space between writing/literature and photography/visual art; how they share so much and yet speak at cross purposes, or don’t speak to each other at all. Catherine and I – she coming from writing but with a history and interest in the image – started a conversation about the crossover between our disciplines. The more we talked to each other, and with others, the more we saw the great interest in bridging these two areas. We ran workshops for the past two summers. When we did the second we knew we were making a MFA, but the first was more an experiment to see if it was a good idea. And the response was great.

Catherine Taylor The idea for Image Text Ithaca came out of an encounter with each other’s work. Once we’d seen each other’s books, we thought that the way our work spoke to each other (about the tenderness and the terror at the seam between private and public, about the tension between materiality and analysis, about the monumentalizing of history, about the haunting resonance of art in daily struggles) deserved more time and attention. And then we encountered this issue of a mismatched vocabulary between the disciplines, which is interesting and provocative but also frustrating. When we started inviting people to the first workshop, they were all extremely eager to participate. Both the writers and the visual artists were happy to spend time together in this exploratory and friendly environment. They were missing this creative and professional dialogue.

NM The people who came to the workshops were established artists and writers whom we invited. And we also did an open call and the response we got was huge – 130 applicants in two weeks. This was an opportunity they’d been looking for and that they just didn’t think existed. Some of them come from traditional photography and writing backgrounds (undergrad degrees from art schools, or writing programmes). Several have already worked on independent or collaborative publishing ventures, including John O’Toole and his Oranbeg Press. A few come from more idiosyncratic backgrounds, which is exciting to me. One was trained as an architectural historian, though she’s also worked with photography and writing. Another was a social worker and community organiser before joining our programme to focus on the writing and image-making that had been taking place in his bedroom. We’re not looking for any particular pedigree – only for open, talented, experimentally ambitious artists.

CT So many of the people said the same thing: ‘I’ve been waiting for this.’

NM One of our graduate students heard about the programme and it made her very emotional because she thought she was all alone in working like this. She just got in her car and drove to Ithaca the next day. I’ve noticed this in photography: so many visual artists have been trying to work with language, especially in books, but they’re missing the discipline and structure to work rigorously with language. And I think many writers are having the same experience with image-making.

NS You’re also integrating The ITI press as part of the MFA. The Press is, as you write, modelled on contemporary photographic and literary small presses, and will publish online and on paper innovative text and image works by national and international writers and artists. Could you tell me more about this?

CT The press is an initiative where the students can learn more about publishing, not just how to be published, but to also how to be editors and curators.

NS Which is something I think we see many younger artists doing today – having all these different hats on, and being able to work in all these fields. This is something also reflected in your own bios.

CT Yes, and we also started the press because we saw a need for this specific kind of press, one that can work with both text and images. I know of a number of photo-presses who do image and text work, but they don’t really have connections with, or reach out to, the community of writers, and vice versa. A myriad of independent presses for literature exist, but they don’t work much with images, or consider the communications between the two genres. There are so few presses that work well with both.

NS Nicholas, you mentioned a poet in the past workshop who collaborated with a visual artist, and they inspired each other?

Matvei Yankelevich, Some Worlds for Dr. Vogt

NM As for collaboration and integrated image-text work, we deliberately have no set expectations, rules or templates. Sometimes collaboration produces a hybrid work; other times, one project or genre simply influences the other. Sometimes a project demands both images and writing; other times, the solution lies in only one medium, even if the insights of the other are important influences. Our past workshops have led to numerous collaborations between a writer and a photographer that have taken several tangible forms. For example, photographer Hannah Whitaker sent images to poet Matvei Yankelevich (both 2014 fellows) who in turn wrote a poem provoked by the photographs. The result was published as an image-text pamphlet as part of the Self Publish Be Happy Pamphlet series. And one of Hannah’s photographs subsequently appeared as the cover for Matvei’s newest book of verse (a fantastic image foreshadowing a truly amazing cycle of poems). All three of our first ITI Press publications came out of collaborations and shared insight during the workshops. What am I leaving out or getting wrong, Catherine? If the coming summer session is a giant bud on the mysterious plant of the previous workshops, what do you hope the hidden flower will look like? Or what will be its fruit?

CT Did you know that cross-pollination often produces plants that are more fertile than their parents? I wish this for our programme: increased fertility, a wildly productive site for future growth, maybe monstrous and beautiful, maybe nourishing, but always vital. Already, the publications from our first year are spreading in interesting ways. For instance, Andre Bradley’s Dark Archives has gotten a lot of attention (short-listed for the Rencontres d’Arles Photo-Text Award) and he continues to produce a series of stunning image-text works, including his latest, Soprano. Claudia Rankine, author of the breakout book Citizen, was an ITI fellow both of the past workshops and included work by another ITI fellow, Michael David Murphy, in her book. Artists and writers Earl Gravy (Emma Kemp and Daniel Wroe), Bobby Schiedemann, Analicia Sotelo and Thomas Whittle collaboratively produced another ITI Book, Tessex, through a process of remote correspondence, curatorial outreach, and an epic road trip. Nicholas collaborated with poet John Keene to produce our most recent book, Grind. And this fall we are publishing a new screenprint portfolio, The Black Banal, by video artist Tony Cokes. I’m in Toronto this week, teaching a writing workshop; half of the manuscripts include photography and everyone’s interested in pursuing work at this intersection. Pretty exciting.

Grind, John Keene and Nicholas Muellner, 2016.

NS I’m intrigued by Claudia Rankine’s Citizen – as I see that many are. These short texts seem to function as images. Grind, as well, seems very funny and important. The cover reminds me of Vibeke Tandberg’s paintings Oblivion, Absence, Disaster, Assumption and Delirium, in which the titles are painted letter on letter, making the words they refer to impossible to read, but lovely text images. I’m not sure, as our synopsis for this issue suggests, about the image as a readable sign. We were inspired by Aperture’s issue Lit. and we want to investigate whether the image has taken over from the word, and if gestures are taking over from images. But I do believe our visual competence is getting better and smarter and that we’re used to and can understand image and text and symbols quicker, which makes it easier to expand our creativity to include different genres. What do you think: will the image take over from words?

CT Nicholas recently pointed me to an essay titled The Caption by Nancy Newhall, which was published in the very first issue of Aperture in 1952. Even then, Newhall wrote, ‘Perhaps the old literacy of words is dying and a new literacy of images is being born.’ She said that ‘photograph-writing’ might become ‘the form through which we shall speak to each other, in many succeeding phases of photography for a thousand years or more.’ But she conceded the continuing role of the textual, saying ‘The association of words and photographs has grown to a medium with immense influence on what we think, and, in the new photograph-writing, the most significant development so far is in the “caption”.’ I think one could argue that there has been a kind of continuing transformation – some might say reduction – of much writing into the function of the caption given the omniscience of the image. So, rather than tackle the unanswerable crystal-ball question of whether images will take over words, it might be interesting to think about whether we agree that language has become subsidiary to image in a caption-like way, or not. And, if it has, are there modes or uses or examples where language as caption might be re- imagined, re-enchanted, complicated or exploded? I’m thinking of the ‘condensary’ (to borrow a word from poet Lorinne Niedecker) of Jason Fulford’s Hotel Oracle, or, at the other end of the spectrum, Nicholas’ expansive captioning in The Amnesia Pavillions. Or maybe Roni Horn’s Still Water (the River Thames for Example), or some of Moyra Davey’s work. Nick, can you think of other examples? Although, I think we do also have to admit that the moving image is the real tsunami, and if we look at words in that context we’d need to talk about the screenplay and the soundtrack and maybe even concede that the photo-text world we’re exploring might be merely a quaint, but still deeply moving, anachronism.

NM I just googled Tandberg’s paintings and the likeness to the Grind cover, by our fantastic designer (and ITI summer fellow) Elana Schlenker, is incredible. The photos in the book are appropriated profile pictures from gay meeting sites, in which the subjects have made formal, usually abstract interventions to hide their faces while showing the rest of themselves – extravagant anonymity, you could say. And Elana, with the cover, went one step further, extracting the shape of obfuscation into a graphic presence all its own. The source, then, has a strong kinship to Tandberg’s spelling of a word that becomes invisible but makes an image all the same. This reminds me why I get so excited about putting writers and photographers in a room to learn from one another. Both fields (as distinct from, say, painting and sculpture) operate with a language that’s everywhere, all the time, and put to the basest and most sublime uses constantly. As I type, thousands of people are texting heartbreaking, syntactically experimental phrases to those who don’t text them back. And just as many are launching tragic and vulnerable images across the ether. But they’re also sending a picture of their rash to their mom, or channelling their high school English training into a well-crafted Yelp review of a Starbucks. My emoji keyboard has five different crying smiley-faces, plus two with Xs for eyes. Words and photographs are constantly put to the most banal and transcendent of uses on such a scale in our lives that we can’t help but question the value of ‘art’ and ‘literature’ as categories of specialised training and expression. But I choose to believe that this surplus or onslaught of image-text production in the world creates a new urgency for the artist – to make of it something other than what’s sweeping us all away like a landslide. The Media Studies scholar Mikko Villi, writing way back in 2008 – just as the first smart phones were hitting the market – had already noted that cell-phone photographs were enacting a fundamental shift in the function of images: to communicate across space, rather than across time. This shifting of the pressure of production to the absolute present is true for language as well. These days, I’m exhausted by this pressure, in which the funny, the tragic and the functional stream by so indiscriminately, but don’t seem to gather downstream in anything that feels like a past. And when would I have time to revisit that anyway? Like the Tandberg paintings Nina described, each expression seems to cross out the last. And it’s the role of the artist to make a complex and enduring form out of that relentlessness. Image and text used together, purposefully, can force us to stop and remember that the world is still unknowable. The oscillation of the mind between an ambiguously linked caption and photograph can do this. As much as images and words flow indiscriminately through the streams of our lives, we still process them differently: one doesn’t show, the other doesn’t tell. Daily life, and the ‘tsunami’ (as Catherine called it) of the moving image both tend to elide that fact in the rush of simultaneity. And that’s where the quaint, anachronistic slowness of still images and written language, given the proper graphic space, can put on the brakes – can force reflection and pause and make a re-humanising allowance for the slowness and uncertainty of knowing. Another route it can take is to theatrically reconstruct the landslide of words and pictures so that it draws and enhances the contours of the crisis of mental and temporal collapse that we’re in. For that, the onslaught of moving image makes powerful sense. I’m thinking of video works like Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue and Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun.

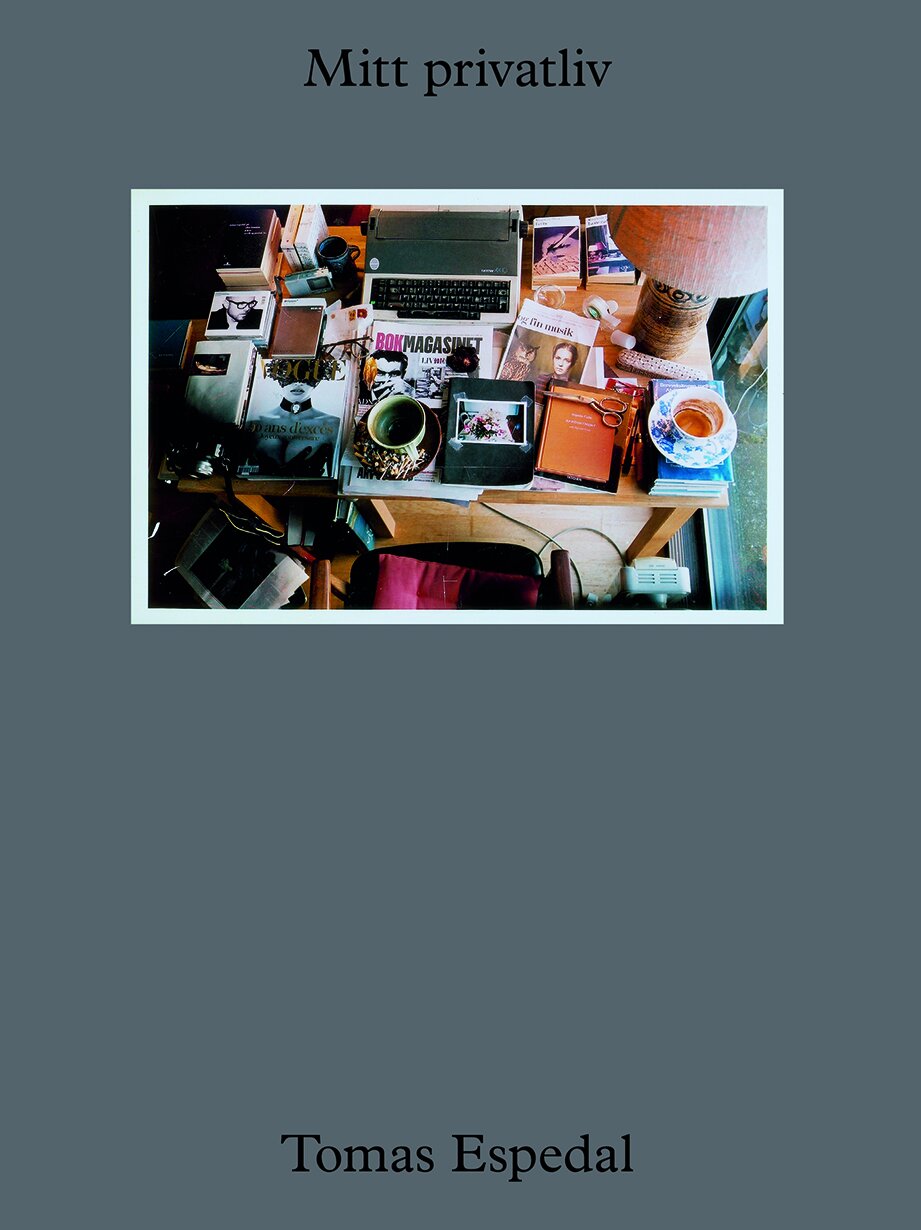

Tomas Espedal, Mitt privatliv, Gyldendal Forlag.

NS How lovely that you should bring up Henrot, Nicholas: her work Grosse Fatigue is featured in our Part 1 of The Flexible Image issues. Tandberg is a good example because she also writes novels, something many other fellow Norwegian artists have done, like Matias Faldbakken, Morten Andenæs and Signe Marie Andersen. The latter has just published her first book with ‘analogue texts’ as she calls them – texts written over many years about images she couldn’t take, or thoughts around how an image could be. She’s just this week having a discussion on her work and on working with image and text together with the writer Tomas Espedal at the opening of Slow Pictures at Lillehammer Art Museum. Espedal himself published his first photobook, My Private Life, last year and has been a fan of photography for a long time, always photographing everything around him. One of the most telling images from his book is an image of his bed and nightstand, with novels and notebooks and drinks and cigarettes all around it. The text accompanying this image says: ‘If one could photograph lovesickness, then this photograph is an attempt: I was about to fall asleep for good, but my writing kept me awake.’ Espedal is one of my favourite writers, and the fact that he uses images makes my belief in the subject of this coming issue even stronger: that texts are becoming images and vice versa, as Nancy Newhall was telling us a long time ago in the essay you mention Catherine, as well as her idea of the caption, which to me is why I like Instagram: it’s a place where you can play with giving the image further meaning through a caption. This weekend I thought some more about poets and images while reading a biography on Louise Bourgeois where she’s trying to understand the process by which a painter like Picasso came to the work he was doing at that time. Looking at the group he exchanged views and ideas with, like Max Jacob and Guillame Apollinaire, she wrote: ‘The poet owns the field of images as well as the field of words. As a creator of images, the poet is close to us, which is why I read Joyce, Jarry, James and Gertrude Stein.’ This might be what my idea of what the outcome of your programme is: owning both fields. To conclude, what are your thoughts on the exhibition mentioned in our issue, SEEABLE/ SAYABLE (Kunstnernes Hus, 2016). Here, the idea of the ekphrasis creates a fruitful approach to the exhibition.

NM I love the idea of ekphrastic texts resonating as spoken language through the exhibition. It really gets to the space between the mental image and the visual image: a seemingly small chasm with no bridge across. It’s a common interest for both me and Catherine. There are many great moments in her writing – in Apart, and her forthcoming book – where language conjures an image that we’re acutely aware we can’t see.

CT My new book’s working title is Inanimate Subjects; it considers military drones, the figure of the puppet, and ideas about autonomy and powerlessness. Because of the nature of drone technology, the question of images we can’t see, image-making that’s largely invisible, and, in fact, world-shaping that happens on an invisible plane both literally and figuratively is very much central to Inanimate Subjects. While I hadn’t really articulated this for myself in the process of writing the book, Nick’s comments about the power of language to conjure absent images is central to that text, and, as he says, to so much writing. My book does include a series of photographs, but I decided not to use military drone views of battle zones or civilian landscapes since those images seemed to overwrite what I was exploring in language. They dominated and reduced. Instead, the photos are of a single puppet in a series of different poses that I hope are evocative of different affects and feelings that course through the writing. In this work, because of the intensity of the subject matter, I hope the photos provide a break, a punctuation, a pause, and maybe a kind of breaking or punching through the page to glimpse something inarticulate the lies underneath it all: that silence that nonetheless speaks.

NM That gap becomes a metaphor for larger (emotional, historical, political) conditions, as much as a way of telling. As the exhibition’s title suggests, hearing a picture is as powerful as seeing one, but certainly not the same. To me, the ekphrastic in literature is just a subset of what great language frequently does: it conjures a powerful image to enact the narrative of projected desire. We produce what’s absent. Sometimes I think the secret that animates language is the invisibility of the image, and the secret of the artwork is its unalterable silence. I’m always thrilled by the two secrets passing each other in the park at night. The encounter is full of mystery, suggestion and insatiable desire.

Nina Perlman, Architects, Pigeons, shortlisted for this year’s MACK First Book Awards. Perlman graduated in 2019.

Since our first edition, published in the spring of 2010, conversations on camera-based art has been the core of Objektiv. Throughout our 20 issues we have always had one or more conversations between artists and others on the scene, conversations that aim to highlight current tendencies in this art practice. We wanted the first book from our Objektiv Press-series to consist of twelve conversations from previous issues and to be launched during this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles. Due to the current situation we will focus instead on our two upcoming essay publications and share (and republish) the dialogues online. This conversation is from our 16th issue.