DEANA LAWSON & ZOE LEONARD

Deana Lawson, Cowboys, 2014, © Deana Lawson, courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago.

By making subjectivity a theme of their work, these artists explore the tensions between conceptions of self and society. Essay by Brian Sholis.

Installation photo from Subjektiv at Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo. Photo by Christina Leithe H.

In recent decades, those of us attuned to art have witnessed a transformation in the narratives about its history. Scholars have begun integrating into the story of art the achievements of those who, because of gender or skin color or geography or chosen medium, were previously unconsidered or deliberately neglected. At the same time, the modernist notion of art’s developmental progression through avant-garde styles has been set aside; now we recognise, even if imperfectly, the multiplicity of every era. These have been welcome developments.

The American historian Daniel T. Rodgers analyzed related intellectual developments through the lens of American culture in his 2011 book Age of Fracture. During the second half of the twentieth century, he noted that:

conceptions of human nature that in the post–World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions, and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance, and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind, the last quarter of the century was an era of disaggregation.

The disaggregation that Rodgers describes has had a political fallout. The Indian essayist Pankaj Mishra, writing recently in The Guardian, called ours “The Age of Anger.” He suggested that what was missing from earlier, more coherent narratives of society was:

the fear ... of losing honour, dignity and status, the distrust of change, the appeal of stability and familiarity. There was no place in [those stories] for more complex drives: vanity, fear of appearing vulnerable, the need to save face. Obsessed with material progress, the hyper-rationalists ignored the lure of resentment for the left-behind and the tenacious pleasures of victimhood.

The economic and political dislocations that revealed these “complex drives,” and our relative inability to perceive and think through them, were on the minds of Objektiv’s editorial board when we decided to produce two issues about the relationship between art, politics, and subjectivity. The efficacy of art in the political arena is perpetually under question. Yet one position to which art’s adherents cling is the value of artists’ insights into present social and political conditions. The five of us, to greater or lesser degrees, share that faith; that is partly why we work as artists, curators, editors, and writers. We asked ourselves: what might artists tell us about the conditions in which we find ourselves? The breakdown of master narratives in art and in politics has reminded those in power that the world contains irrepressible multitudes. The art in these pages and in the companion exhibition reminds us that individuals relate to the world from multiple subject positions, and that the influences on those subject positions are being radically reshaped – especially by networked-image technologies. And while there is a sense that the shared public space of politics is currently being overwhelmed by affective content, we are simultaneously witnessing a reinvigoration of the power of the collective and the resolve of communities. By making subjectivity a theme of their work, the eight artists and artist groups included here can help us imagine novel links between individual and collective experience.

Deana Lawson, Nicole, 2016, © Deana Lawson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Though their art takes varied forms, each artist makes images with – or uses images made by – cameras. For 150 years, the mechanical nature of the medium suggested a particular claim on documentary veracity, on “truth.” Today, viewing publics increasingly recognize photographs as subjective, rather than objective, documents. We know that pictures carry the biases of their makers, and that our interpretations of them reflect our biases in turn. New questions have arisen: how do we apportion our attention when our media feeds include traditional journalism, internet gossip, propaganda, fake news, and the opinions of friends and family? What is at stake when subjective criteria and utterances have entered the political environment on an unprecedented scale? These questions connect in fundamental ways with our understanding of the camera as subjective narrator and a technology of perception.

While some works in this issue question how personhood is defined, negotiated and legislated through photographic representation, others reflect on the discrepancy between physically grounded and immaterial ways of existing as humans, and on how deeply embedded we are in other life networks and ecologies. The self is no longer necessarily understood as singular; we acknowledge the extension and molding of subjectivity via screens and technologies and via myriad other practices: consuming, naming, performing, branding, liking, hosting, acting and, of course, recontextualizing.

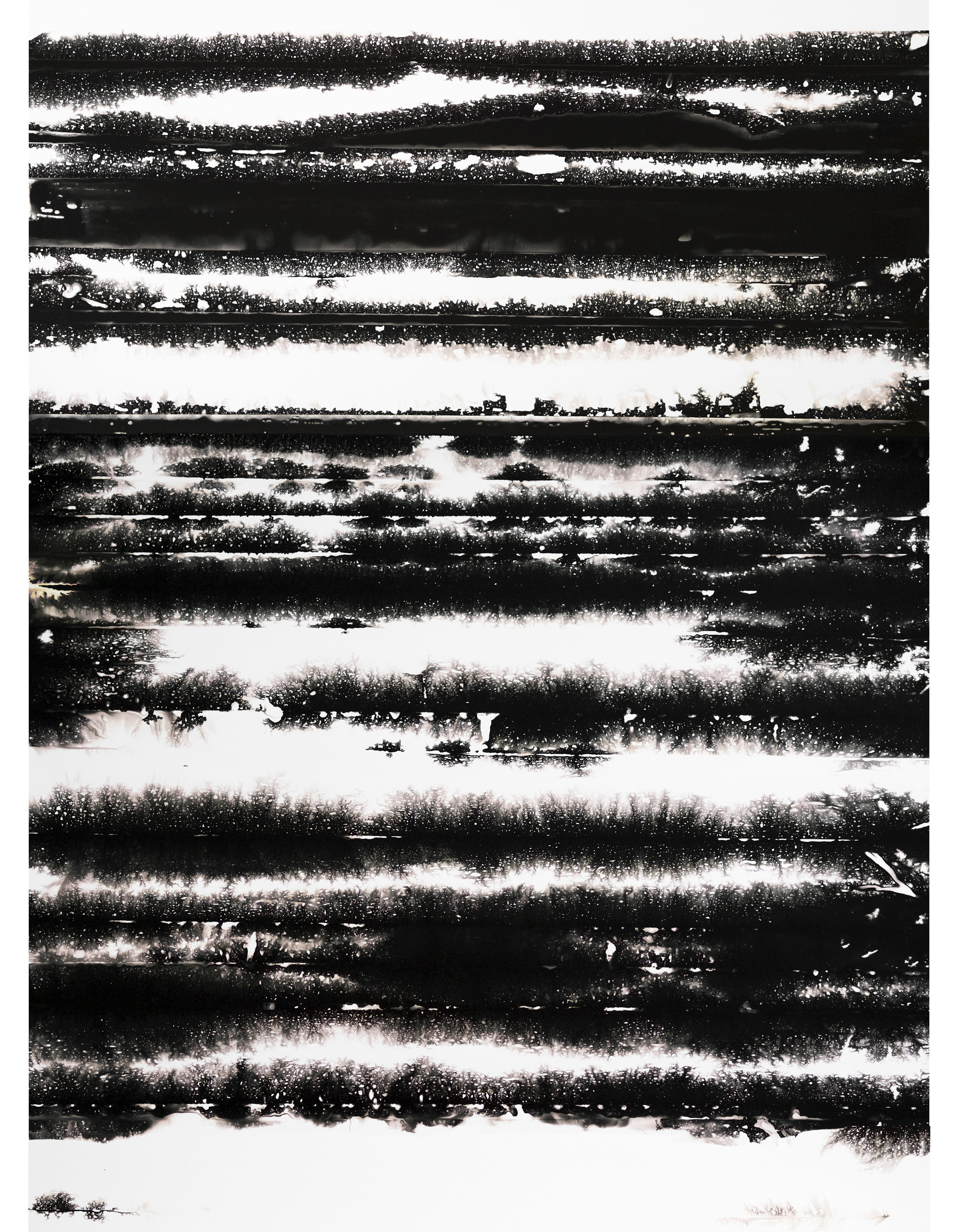

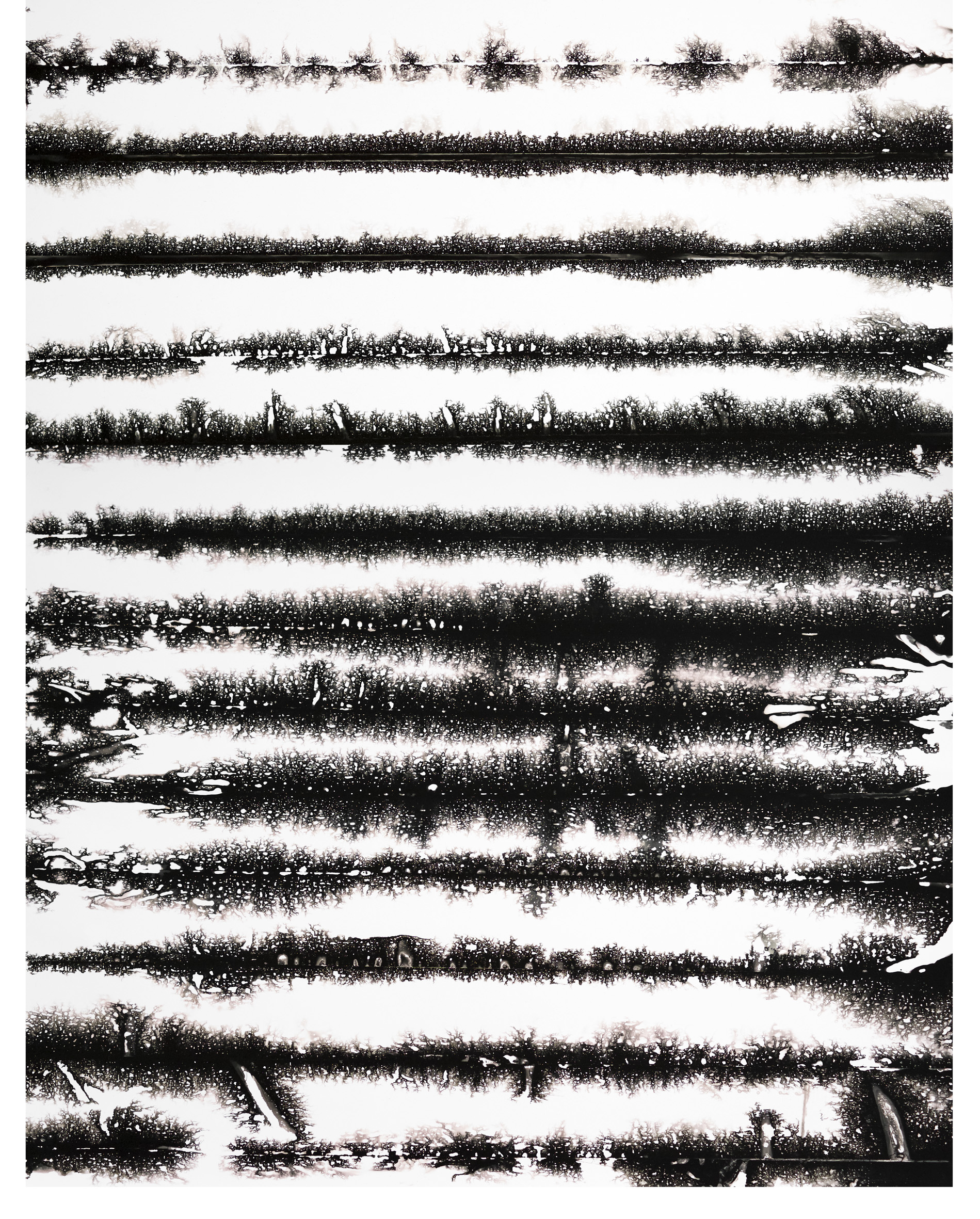

Consider American artist Zoe Leonard’s recent photographs, presented in New York last year in an exhibition titled In the Wake. They depict family snapshots from the period after World War II when her forebears were stateless. The original images, taken as her family fled from Warsaw to Italy to London to the United States over the course of more than a decade, offer scenes of intimacy that contrast with the era’s international clashes and their messy aftermaths. Leonard, in re-photographing the originals, opted not to reconstruct lost moments, to close the gap between then and now. Instead, she examines the earlier photographs as printed objects that bear physical evidence of their own histories: we see scratches and other blemishes, edges of paper curling upward. Sometimes, too, Leonard aims her camera from an oblique angle, shrouding the original subject with a splash of reflected light and revealing a wavy postmark. (These objects made the same journeys as their subjects.) She flips one photograph to document its inscription. “It’s not that one sees less,” Leonard has explained of these works, “but that different information becomes visible.”

Leonard’s artworks are in the “wake” of the originals in multiple senses. A wake is the path behind a ship marked by choppy waters – a useful metaphor for migrants seeking safe harbor, as the pictures’ subjects are doing, or for the compositions, in which the originals “float” against featureless backgrounds. A wake is also the act of keeping watch with the dead, of meditating on lives as they were lived. For every migrant who forged a life in a new home, as did some of Leonard’s family members, there are others who could not. And to “wake” is to come to consciousness, to become alert to the world around you when before you were unaware. The narrative emphasis placed on their subjects’ statelessness ensures the pictures’ relevance in our present moment of geopolitical instability and its attendant migrations. These intimate pictures are linked to – awaken us to – some of the broadest and most pressing social concerns of the day. Many of the original pictures are bounded by thin white borders. By re-photographing them and placing them within this conceptual and narrative framework, Leonard ensures that the meanings they convey are not similarly restricted. We know little about the lives of the people depicted, the knowledge of which remains the province of Leonard and those close to her. But in imagining those stories, empathy compels us to relate at both intimate and grand scales.

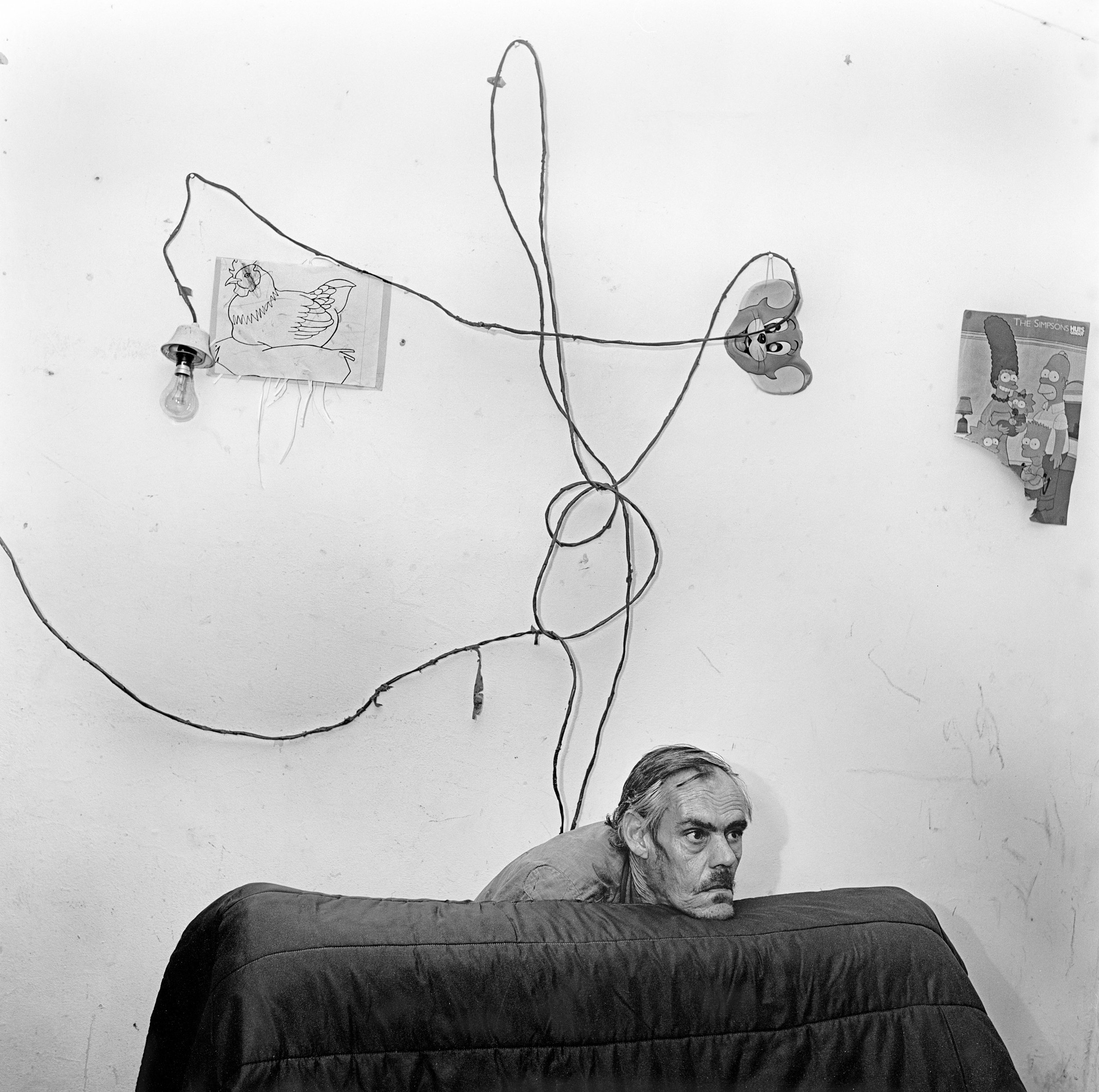

In a 2011 interview, Brooklyn-based artist Deana Lawson, whose work one might not readily associate with Leonard’s, spoke about family albums:

I think that there is definitely something tragic in the family photograph – it’s a fundamentally retroactive idea. We make the image specifically to look back on it, to refer to it later in life. Even in my old family albums, the process of aging – the space between then and now – can be haunting and unstable. How to deal with the idea of projected time in a static medium is an interesting challenge.

Lawson describes the subjects of her photographs as “her family.” Given the seeming intimacy of her pictures, the term makes intuitive sense. But she is not related to them by blood; in fact, most are strangers cast for their roles by the artist, who plans each composition and arranges the many details. To date, she has done this work with subjects living in Haiti, Jamaica, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, and in various parts of the United States. As the statement above suggests, Lawson uses the visual conventions of family albums merely as a starting point. “In my portrait work,” she says, “I am creating ... a theater of the family snapshot.”

Deana Lawson, Ring Bearer, 2016, © Deana Lawson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

The metaphor seems particularly apt: her compositions often function like proscenium stages on which her subjects perform their intimate gestures. They are pressed against a wall, or, if outdoors, against foliage or the blackness of night. Lawson usually points her camera directly at them and they stare back into the lens. This interaction feels matter-of-fact, rather than confrontational, and contributes to the pictures’ sense of candor. The small dramas that Lawson has scripted are about flesh, kinship, sex, rituals. She is attuned to Black self-fashioning, to traditions of representing Black bodies by non-Black artists, and to the interaction between these aesthetic programs. As the critic Greg Tate has noted, Lawson’s work “seems always [to be] about the desire to represent social intimacies that defy stereotype and pathology while subtly acknowledging the vitality of lives abandoned by the dominant social order.”

The constructed intimacy of Lawson’s pictures hints at a shift in our everyday use of cameras and our approach to photographs. Let’s call it “stage awareness.” We perform for the camera, as we always have. Then we manipulate our pictures, as has been common since the smartphone revolution. But now we distribute them through channels that do not let us assume the size or makeup of our audience. The dominant form of self-fashioning, thanks to networked distribution, is entirely public-facing; we create versions of ourselves meant for consumption by others both known and unknown. The source material in Zoe Leonard’s In the Wake artworks marked significant occasions for a specific set of people. That kind of intimacy no longer characterizes most of our photographs. The fact that they are objects, too, would be unusual now; images are currently printed less often than they are shared across screens. (This is another kind of passage or migration.) Today, we place our immaterial images in public venues and we respond to images by others created expressly to be circulated. We are only beginning to understand what this echo chamber of manipulated images suggests about how we relate to one another.

We know that, in the past, photographs produced for wide distribution were often altered to better reflect cultural norms. (Think of fashion-magazine covers.) Those alterations helped the images’ subjects fit more comfortably into networks of economic exchange. If altering our own pictures for others’ consumption is now a default practice, then the work of Brooklyn-based Canadian artist Sara Cwynar can help us to understand how the value of images shifts through circulation and across time. Cwynar gathers mass-produced objects and commercial images, often made during the 1960s and 70s, and recontextualizes them in her studio. She nestles physical objects alongside printed photographs of them, or of other materials. Then, through a laborious process of photographing, printing and e-photographing, she creates collage-like images that reflect upon consumer desires and the visual strategies used to stoke them. “Looking critically at not only mass-produced objects but also mass-produced modes of depiction is a kind of political project,” notes the artist in an interview in Objektiv 15.

The political implications of our visual rendering of the world is what unites the artists included in our exhibition, although in disparate ways. Sandra Mujinga reflects upon what she terms the “poly-body” in her investigations of the digital self. The collage project ALBUM by Eline Mugaas and Elise Storsveen offers a highly subjective take on photographic representations of gender, sex, and the concept of care. Liz Magic Laser uses the format of the TED Talk in a film installation featuring a ten-year-old actor delivering a monologue adapted from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground. In this way, her work relates the author’s attack on the socialist ideal of enlightened self-interest to contemporary capitalist thinking. Another film installation by Basma Alsharif addresses both the stateless self and mass-mediated representations of trauma on the Gaza Strip. Josephine Pryde speaks of a different form of displacement in her series It’s Not My Body, which superimposes found, low-resolution MRI scans of a human embryo in the womb against desert landscapes shot through tinted filters. She engages multiple definitions of “reproduction” and their impact on political debates about subjecthood and a woman’s right to choose.

We decided to include one artwork made during an earlier era, namely Zoe Leonard’s 1992 text I Want a President. When speaking about it in late 2016, the artist noted how her relationship to its call for a new politics has evolved. “On the one hand, I’m thrilled and gratified that something I made more than twenty years ago might still be considered relevant. At the same time, I am utterly horrified and saddened that these words still have such relevance.” She added: “I don’t think about identity politics in the same way – that is, I don’t think that a specific set of identifiers or demographic markers necessarily leads to a particular political position.” Having to acknowledge the uncoupling of political views and individual attributes seems to us a key development during the past twenty-five years. This complicates, rather than negates, identity politics, and the ways in which we produce and respond to images have played an important role in this evolution. Today, individual and collective identities are fluid, and the distances between them fluctuate. The artworks gathered help us to distinguish whether those distances are intellectual, emotional, or psychological. And, if we are open to them, they can illuminate the paths we navigate between self and society.

Deana Lawson, Joanette, Canarsie, Brooklyn, 2013, courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago.