HAGEN HOPKINS

Hagen Hopkins. GETTY IMAGES.

Afterimage by Kate Warren: I was excited to participate in Objektiv’s “One Image” column, but trying to pick a single photograph to write about was more difficult than I had imagined! With so much conflict and uncertainty confronting our societies and communities today, choosing one image to represent everything that is currently on my mind felt like a slightly overwhelming task.

In the end I settled on this photograph, taken on Friday 15 March 2019 at a Climate Strike rally in Wellington, New Zealand. The photograph’s frame is filled with a large group of young people, many holding signs and placards with their mouths open, fists raised, and hands poised mid-clap. Most of their gazes shoot off in different directions, towards each other or attracted by action happening outside the frame. In the middle though, one of the young girls appears to be looking directly at the camera, as she raises her cardboard sign above her head. Whether or not she was actually addressing the photographer directly hardly seems to matter; the centrality of her gaze and her message creates a moment of individual interaction amongst the large crowd.

The slogan drawn on the girl’s sign, “There is no planet B!”, also caught my attention. Across these young people’s protests – which have been inspired by Swedish student Greta Thunberg – the intelligence, emotion and humour of their slogans, speeches and calls to action have been impressive and inspiring. They are reminders of the political and visual literacy that young people possess today (even if some of our politicians would seek to deny and refute the political agency and engagement of younger generations). Yet amongst all the diverse and creative messages held high on these young protesters’ signs, some slogans proved particularly popular and recurrent. “There is no planet B!” is one such example. I spotted it on signs from Hong Kong to Gibraltar, South Africa to France, Australia to Germany, and more.

This slogan is effective for a number of reasons. By evoking a scenario of pure science fiction – for example, think of the “Off-World Colonies” in Blade Runner – the slogan in fact reasserts the reality of our present. It conveys a visually evocative sense of urgency. My mind goes, unsurprisingly, to the famous “Blue Marble” image taken by NASA astronauts of the Apollo 17 mission. Of course, it is quite likely that somewhere in the universe, there could be planets similar to Earth that are sustaining sentient life. However, the reality of climate change means that for human and non-human animals on Earth, there really is no Planet B to escape to.

Photographs of children and young people are inherently symbols of the future, of lives not yet lived and potential not yet filled. Yet this slogan, and indeed the multitude of images of Climate Strike protests, evoke an impossible future. They speak to the uncertainty and anxiety that is palpably affecting these young people. As Australian academic Blanche Verlie has written recently, climate change is fundamentally changing “young people’s sense of self, identity, and existence”. They are the first generation to have only known a world under catastrophic threat of climate change. These protests and images are about recasting dominant symbols and narratives of the future; hopefully, their urgency will transform older generations’ perspectives and actions towards the future as well.

BJØRN OLAV BERGE

Photographs by Bjørn Olav Berge.

Afterimage by Arild Våge Berge:

These photographs were taken by my father when he was 13 years old, during the live broadcast of the Apollo 11 Moon landing on 20 July 1969. He shot the images that were on the TV screen, developed them himself in a darkroom and mounted them on a piece of cardboard.

I can remember these pictures hanging on the wall in his room in my grandparent’s house. When my grandparents died, my father inherited their house. The photographs disappeared for a while, but I recently found them lying on the floor in a dark corner of the cellar.

I’ve never asked my father why he took these photographs, but what I see in them is an eagerness to hang on to what must have been a fantastic moment. There’s something beautiful in the belief that it would be possible to preserve the aura of this transmission of an event that was taking place on another planet by photographing it.

Before the signal finally hit screens in numerous countries on Earth, watched by around 600 million people, there was a time delay when all that was visible was the frame-rate number and band-width conversions. What is actually seen in my father’s photographs is the noise and disturbance from these electrical conversions, radiation and signal enhancement; not to mention the paper discoloration, scratches, dust, dents and stains from the decomposition of the print materials. Yet in this accumulation of noise and distortion I find myself staring directly into my father’s moment of wonder. To me, it looks as if he was there, when humans were stumbling around on the surface of the Moon like children, in a triumphant achievement of modern technology. It is because of the disturbances of mediation and the decay of the prints that I accept this truth of the document. And although great efforts were put into the precision of broadcasting the event and the photographic documentation made by my father, it is in the failure of this precision that I find authenticity.

After the images’ proud days on the wall of my father’s room, they lapsed into waste on the cellar floor, but on rediscovering these old artefacts, discarded and forgotten, I decided to take them with me. By doing this, I’ve become the protector of the gaze of my father as a child, and maybe also the gaze of the world in a brief moment when human technological achievement seemed boundless.

LEWIS BALTZ

Lewis Baltz, Cray, supercomputer, CERN, Geneva.

Afterimage by Rémi Coignet:

I was invited by Objektiv to choose and present one photography. The one I landed on is Cray, supercomputer, CERN, Geneva by Lewis Baltz. The work is drawn from the series Sites of Technology. It is perhaps not the most representative work of the rather dark spirit of the series, and I could have chosen a dozen others ones, even the whole book, but I play by the rules.

Cray, supercomputer, CERN, Geneva expresses the naive optimism inspired by the pop culture that surrounded the first, pioneer years of the computing network. It also translates the realism of the period, linked to Lewis Baltz's unstoppable humor facing the real world moving towards virtualization. So what do we see? In the center of the composition we identify something resembling yellow and blue sculptures, and at their right several monitors seemingly there to pilot the technological looking sculptures.

It was between 1989 – 1991 that Lewis Baltz conceived the series Sites of Technology. The work is his very first one executed fully in colors, and it is also his last book consisting solely of photographies. It was published tardily by Steidl in 2007, under the name 89/91 Sites of Technology.

Since then, Baltz focused on installation works such as Ronde de nuit as well as other various public projects or site-specific works. (1)

When I asked him about this radical choice, to renounce on the book as a "pure" expression of photography, he answered me: "After 1990, no one had time for documentary images, least of all me". (2)

The color first appears in Baltz's work through Candlestick Point (1989), a work standing out from a selection of mainly black and white images. The colors are neutral, cold scaled, unadorned. Once again, when I asked about this sudden introduction of color, he gave me the following reply inspired by Stanley Cavell: "Black and white imagery suggests the past [...]. Color suggests a future that has already begun". If we accept this way of reasoning, we can probably explain the vibrant colors of Sites of Technology as a premonition of our contemporary 2019. This underlines the visionary character of Baltz's work: "It interested me to photograph something that was impossible to photograph.[…]. Because in fact you couldn't see what was really important".

In 1991, the Internet only regarded engineers, computer professionals, and programmers. The Web was only emerging. Sites of Technology was mostly photographed in France and Japan, depicting primarily what was a the time called "supercomputers". They were used by scientific research centers as well as mail-order companies (using catalog paper). This was long before Amazon entered the stage.

More than one billion two hundred million photographs were taken in 2018, mainly with smartphones. Most of them still sleep in the flash memories of our phones, on the hard drives of our computers or on server farms spread out over the four corners of the earth, and they will never be edited. Never have the number of published photography books been higher. At every moment, we are swimming in an ocean of photographies serving the sake of publicity, propaganda or plain narcissism. Paraphrasing Daniel Arasse: we cannot see anything anymore. And it is indeed this future extinction of the image, omnipresent and at the same time a digital ghost, that Lewis Baltz ingeniously predicted with Sites of Technology.

We now know that Lewis Baltz never ceased to photograph, principally in the Italian region Mestre. This can be further discovered in a book that will be published in a few months, following Baltz’s will, five years after his passing.

The quotes from Lewis Baltz are drawn from the interview he granted me for my book Conversations, The Eyes Publishing, 2014.

En Français :

À la demande de Objektiv j’ai été invité à choisir une photographie. J’ai opté pour Cray, supercomputer, CERN, Geneva de Lewis Baltz Cette photo est extraite de Sites of Technology. Elle n’est peut-être pas la plus représentative de l’esprit assez sombre du livre et j’aurais pu en choisir une dizaine d’autres ou même le livre entier. Mais tel était le jeu.

Cray, supercomputer, CERN, Geneva traduit à la fois l’optimisme, un peu béat encore, inspiré de pop culture de ces années pionnières des réseaux et en même temps le réalisme lié à l’humour imparable de Lewis Baltz face au monde réel ou en voie de virtualisation. Qu’y voit-on ? Au centre ce qui ressemble à des sculptures jaunes et bleues et à droite des moniteurs que l’on suppose devoir piloter ces « œuvres » technologiques.

Entre 1989 et 1991 Lewis Baltz réalisait donc sa série Sites of technology. Il s’agit de son premier travail entièrement conçu en couleur. Cela sera également son dernier livre strictement photographique.

Il ne sera publié que tardivement en 2007 par Steidl, sous le titre 89/91 Sites of Technology.

Dès lors, il allait se consacrer à des installations comme Ronde de Nuit (1992) ou à des publics projects ou des site-specifics works. (1)

Lorsque je lui posais la question de ce choix radical, de renoncer au livre comme expression de la photographie « pure » il me répondit : After 1990, no one had time for documentary images, least of all me. (2)

La couleur apparaît dans l’œuvre de Baltz dans Candelstick Point (1989) mêlée à une majorité d’images noir et blanc. Les couleurs y sont neutres froides, factuelles. Encore une fois, lorsque je l’interrogeais sur cette introduction de la couleur, il me fit cette réponse inspirée de Stanley Cavell : Black and white imagery suggests the past [...]. Color suggest a future that has already begun. Si l’on suit ce raisonnement, on peut sans doute induire que les couleurs vibrantes de Sites of Technology suggèrent notre présent de 2019 (donc un futur alors pressenti) et rend visionnaire le travail de Baltz : It interested me to photograph something that was impossible to photograph.[…]. Because in fact you couldn’t see what was really important. En 1991 Internet n’était alors encore qu’affaire d’ingénieurs, d’informaticiens et de programmeurs. Le Web était naissant.

Sites of Technology a été principalement photographié en France et au Japon, représentant pour une large part ce que l’on appelait alors des « supercalculateurs », utilisés aussi bien par des centres de recherche scientifique que par des entreprises de vente par correspondance (sur catalogue papier). Bien avant la naissance d’Amazon.

Plus d’un milliard deux cents millions de photographies ont été prises en 2018, principalement avec des smartphones. La plupart dorment dans les mémoires flash de nos téléphones, sur les disques durs de nos ordinateurs ou dans des fermes de serveurs disséminés aux quatre coins de la planète, et ne seront jamais éditées. Jamais autant de livres de photographie n’ont été publiés.

Nous nageons à chaque instant dans un océan de photographies publicitaires, propagandistes ou narcissiques mais pour paraphraser Daniel Arasse, on n’y voit plus rien. Et c’est cette disparition à venir de l’image, à la fois omniprésente et en même temps devenue pur fantôme numérique que Lewis Baltz a génialement pressentie avec Sites of Technology.

L’on sait désormais que Lewis Baltz n’a jamais cessé de photographier, principalement dans la région de Mestre, ainsi que l’on pourra le découvrir dans un livre à paraître dans quelques mois, suivant sa volonté, cinq ans après son décès.

Les citations de Lewis Baltz sont extraites de l’entretien qu’il m’a accordé pour mon livre Conversations, The Eyes Publishing, 2014.

Rémi Coignet lived and worked in Paris as an editor and writer. This text is translated by Ingrid Holden.

ISA GENZKEN

A spread from Isa Genzken’s Mach Dich Hubsch!

Afterimage by Jenny Kinge:

It was with great anticipation that I walked up the stairs of the Martin-Gropius-Bau, the solemn building on the former border between East and West Berlin that hosted Isa Genzken’s exhibition Make Yourself Pretty! As I wandered through the comprehensive collection of the German artist’s sculptures and installations, with their wide-reaching cultural references, I was taken by surprise by a re-encounter with a long-forgotten idol of mine.

The photo of Leonardo DiCaprio, with his slick hairstyle and cute smile, bound up with sticky tape and juxtaposed with bold colours and elements containing the word DUDE, was part of a rich collage unfolding over the many pages of Genzken’s diaristic book Mach Dich Hubsch!

My crush on Leo had manifested itself through the posters, diaries and magazines I bought in the late 1990s, all furnished with his smiling face. My re-encounter with the young movie star stirred up many memories. When facing the image through the glass vitrine, I felt as if I’d been caught red-handed: the work reminded me how I had wholeheartedly worshipped this dandy as a young girl. I didn’t reflect upon the consumerist aspect of this ‘love affair’ at the time. The material culture crept up from behind, as it still does – my identity is unintentionally affected by my acquisition of things.

I left Martin-Gropius-Bau with a new crush that day – not on Leo, but on the eye-opening work I’d just seen.

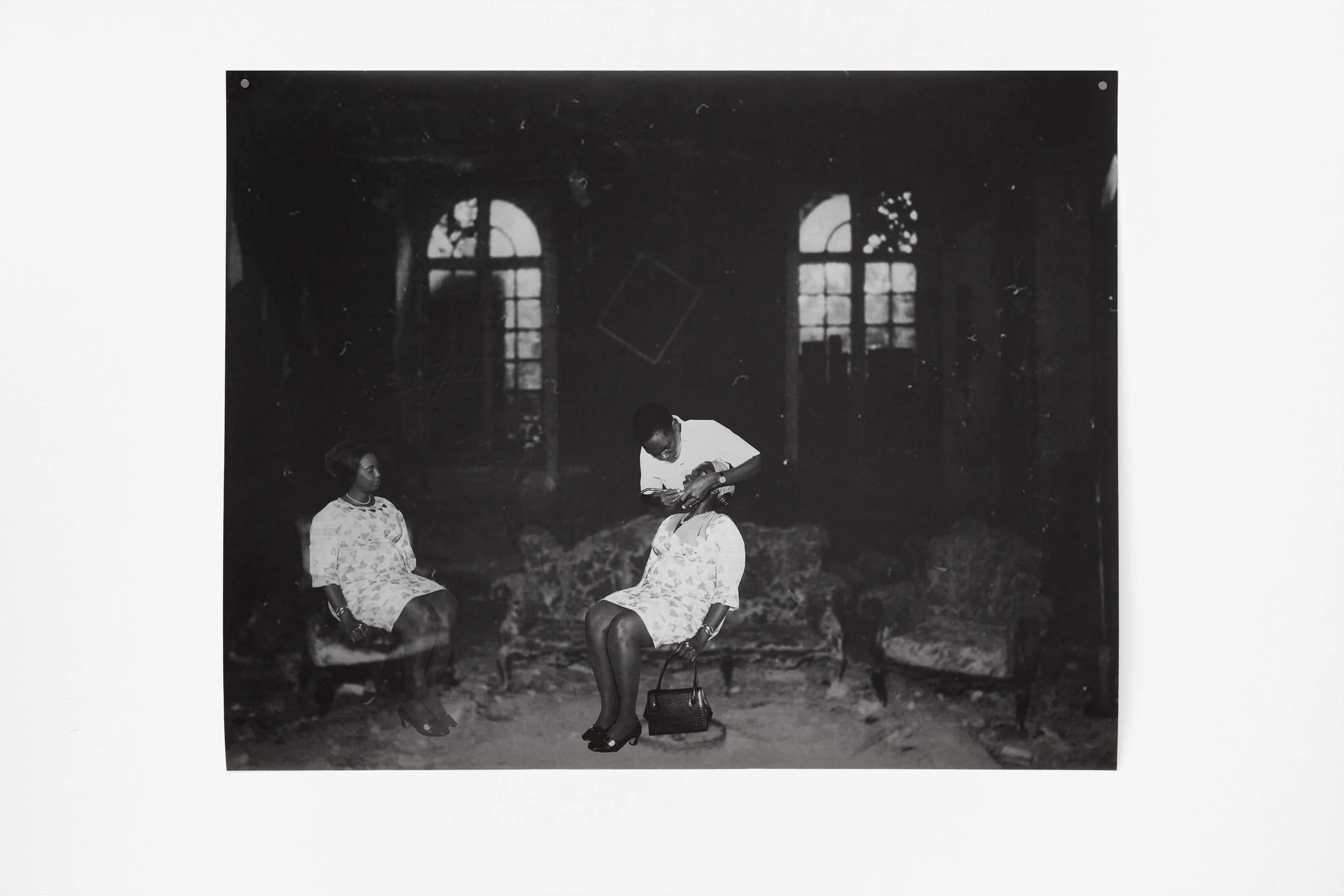

FRIDA ORUPABO

Afterimage by Ruby Paloma:

I first saw Frida Orupabo’s work last year in Arthur Jafa’s exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Berlin. I have carried Frida’s Untitled (2018) with me since. I have been searching for a means to contribute to the nearly invisible topic of race in the visual art discourse in Norway and Frida’s work struck me at the exact right moment.

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2018, digital C-print, 89 x 105 cm, Courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake and the artist.

I don’t care for Instagram so I was relatively late to discover the work of @nemiepeba. I had no idea Frida was Norwegian, and that she lives about 300 metres away from me in Oslo. She is half Nigerian, like myself. I was stunned. Not because another Norwegian-Nigerian woman with a cultural agenda lived nearby, but because one of this country’s most significant contributors to Blackness in visual culture had been right under my nose for some time. I had never heard anyone talk about Frida, never seen her work included in a show nor seen her at an opening. It seemed that Frida’s almost unbelievable path to international fame had gone unnoticed to most in the Oslo art scene; Arthur Jafa’s crucial advocacy for Blackness, and use of Instagram, was in other words decisive for her breakthrough.

The role that a digital platform has played in disseminating Frida’s work (and her discovery) can be argued to be a democratisation of hierarchies in the art world, but it seems less relevant to me as @nemiepeba had little effect on the local audience, even more so because I first saw Frida’s work as enlarged collages; collage being the only thing I am certain about in the search for an expression for Blackness in Norway. Formally emerging from the philosophy of Dada artists and their distrust of rationalism and the order of civilisation, collage seems naturally suited to re-build social structures, comment on racial hierarchies, politics and culture, and display the complexity and nuances of a dispersed identity.

Frida’s digital collage of two black women and a black male dentist in a manor house combines WTO vintage photographs from Uganda (c.1970s) with Nona Limmen’s “Photogenic 18th century mansion captured on Polaroid”. For years, Frida has created an archive of images found online and used it as the basis for her digital and physical collages. She is interested in how we see things: race, sexuality, gender, family relations and motherhood, and by combining images that are not meant to be together, she challenges how we understand and talk about the arrangement of things. In Untitled it is unclear which bodies and actions belong where and when. Do black bodies (not) belong in (abandoned) mansions? Does the work of a black dentist belong there? The women are similarly dressed with identical shoes and bracelets and their dresses have the same pattern. How many times have I not been mistaken for someone with the same skin colour as myself?

The art of Frida Orupabo, both on and off Instagram, is of tremendous importance in promulgating Blackness in Norway. The lack of visible focus on the topic makes it seem like no one is working on it, making it harder to locate each other and start the discourse that will help build an identity around being brown or black in Norway today. Luckily, the Norwegian art institutions have now noticed her, and she is opening her first solo exhibition in Norway at Kunstnerens Hus on 1 March 2019.

PATRIK RASTENBERGER

Patrik Rastenberger, from the series Küme Mogñen – a healthy mind in a healthy land, 2018

Afterimage by Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger:

Two photos of destruction occupy my mind. They show no corpses, blood, gestures of desperation, or homes in ruins. Instead, the destruction takes the visual form of a landscape, with the reference imprinted in a surface pattern or abstraction across time. This photographic method could be even termed ‘aftermath photography’: the photos abstract from the traumatic historical events taken as subject matter. In both cases, the photographer has arrived on the site years or decades after the conflict.

Ritva Kovalainen & Sanni Seppo, Sateenkaarenpää (The end of the rainbow), 2007/2019

In the photo by Patrik Rastenberger eucalyptus trees are planted where a natural forest once stood. Eucalyptus forests grow rapidly, and the wood is ready for harvest every 10–15 years. That makes them attractive in places such as Chile, where this photo was taken. Here, eucalyptus is an invasive species supplanting natural forests. The leaves that fall from eucalyptus trees are acidic, killing the species-rich undergrowth as they decompose. Also, they need vast amounts of water, so the area grows drier and habitats change. Such overexploitation of resources and cultivation of nonnative species at the expense of variety are among the greatest factors in erosion of biodiversity. Biodiversity involves genetic development of the species tapestry over time, into rich and resilient ecosystems, and it is often measured in the species count: 1 in this photo.

The second image was captured by photographers Sanni Seppo and Ritva Kovalainen, long-time forest activists in Finland: Photography is their main weapon against state forest policies that entail a shift from natural forests’ diversity to managed ‘fields of wood’. Their long-term projects have investigated clearcutting of natural forests and its effects at ecosystem level, in how both biodiversity and human lives suffer. Such images portray another face of climate change and habitat destruction/fragmentation: we zoom out to sterile manmade lines, stark patterns in biodiversity’s decline.

Both photos represent forests, but they do far more when read in the context of reduction of biodiversity. They are two ways of answering the question I pose of how to visualise lost diversity and richness, now replaced with a diversity-poor monotone. How can we show the absence of thousands upon thousands of species, which once inhabited these forests and composed a rich ecosystem? The invisible massacre in our environment.

The battle over knowledge and its control and distribution has become a defining development of our time. However, the question about photography is an old one: how photos visualise something that cannot be seen and, further, how we read in them something that is absent.

STEIN RØNNING

Stein Rønning, ROUTHE II, 2014. Lightjet on paper, 86 x 63 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galleri Riis.

Afterimage by Kåre Bulie:

Why am I so enthusiastic about Stein Rønning’s photographs of boxes that I just never forget them? Since 2008, I’ve followed, with a growing fascination, the development of these images moving from one exhibition to another – in Arendal, in Oslo, in Kristiansand, and once again in the Norwegian capital. I’ve also written about them on several occasions. When Objektiv asked me to contribute to the "On my mind”-column, Rønning’s “object photographs”, which the artist himself has called them, were the first pictures that came to my mind, even if it’s been a while since I’ve seen them outside of the internet.

For those who don’t know them, these works might seem dry, almost evasive in their ascetic elegance. For whoever gives them time and attention, there is much to discover and reflect further upon.

The creation process is complicated: The artist, originally known as a sculptor, and who still exhibits physical sculptures in addition to the photographs, first makes the boxes. He then places them together in continually changing combinations and photographs them. The photographs Rønning presents are also processed digitally – the same box can, for example, be seen in several places in one and the same photograph. Under changing titles, throughout more than a decade, the artist has worked with what is fundamentally the same project. There is nonetheless variation: in colouring, scale, composition, and the creation of space. Some of the photographs give associations to painting and consequently open for reflections on a third medium.

I think my enthusiasm for these images has to do with how they bring together so much of what interests and excites me. First of all, there is something arch-modernistic about the universe of forms in Rønning’s works, which mobilizes my fascination for the entire history of modernism. Secondly, the box project is an example of an art that is exciting to look at and interesting to think about at the same time – visually striking and intellectually stimulating in equal measures. This is not at all an obvious combination in this day and age. Third of all, these motifs have something markedly architectonic about them, which agrees especially well with someone who has always had parallel interests in visual art and architecture. The Rønning photographs steer the thoughts both to the adults’ Manhattan and to children’s building blocks. Like many of his modernist colleagues, in his art, Stein Rønning points at the potentially great significance of the small difference – and at the richness that reduction and concentration can lead to.

ROBERT HEINECKEN

From Robert Heinecken's series Are You Rea (1964-68)

Afterimage by Matthew Rana:

Seduction belongs to artifice. It's a play of surfaces and transformation, disappearance and gestural veils. In other words, seduction is fleeting and mysterious, it takes what's visible and licks it with falsity. On a different register, pornography might be pure allegory: forced over-signification verging on the baroque. With its graphic disclosures, pornography points to an external logic, an invisible power that determines what can be seen. More simply put, it leaves nothing to the imagination.

Unlike his more libidinally charged works that actually make use of pornographic imagery, Robert Heinecken's series Are You Rea (1964-68) seems to negotiate the tension between these two poles. In the 25 photograms, magazine pages featuring advertisements for products such as cosmetics, cigarettes, lingerie and spaghetti, are juxtaposed with images of police violence, protests and photo essays on reproductive rights. Layering image on top of image, recto and verso are flattened, so to speak, onto a single surface. The compositions are chancy and ironic; everything is inverted and continuity and scale are confused Often full of sex appeal, the images in Are You Rea also indicate a loss of coherence, a figuration that is ghostly and at times grotesque. But despite all their violence, fragmentation and internal dissonance, they seem less about critique or defamiliarization than they do correspondences. Because if archives create the illusion of totality by making gestures of equivalence between things archived (i.e., between an ordered multiplicity of things, indexed and gathered together to be read as a single entity), Heinecken's series is archival in that it suggests a deep and dark unity.

I think this might be part of why his work still looks so fresh to me, especially the photograms. It's their insistence on materiality and distribution. What I find across the multiple surfaces, in the patterned utterances and the vulgar repetitions, is not the reality that's hidden behind appearances. Rather, it's the spatialization of circulatory and temporal relationships, of reading and discourse. If speech takes place at the intersection of material and social forces, then this is how the archive surfaces – a shifting assemblage of contradictory and inconclusive statements – iterative, synthetic, hardcore.

HARRISON SCHMITT

Commander Eugene Cernan After Three Days of Lunar Exploration. Photographed by Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 17, December 7-19, 1972, Michael Light, Full Moon. Transparency NASA © 1999 Michael Light

Afterimage by Laara Matsen:

Taken by fellow astronaut Jack Schmitt as a sort of snapshot, and part of NASA’s extensive and wonderful archive of space imagery, this photograph is of Gene Cernan, Commander of Apollo 17, the last man to walk on the moon. I came upon it years ago, hanging on the wall at the Museum of Natural History in New York, and it resonates with me still. A man at work, covered in moon dust, exhausted and seemingly content, the image speaks to me of the quieter side of grand adventure. Exploration of the unknown is a romantic and exciting notion by nature, and one that led me to photography (among other endeavors) in the first place, but I am especially taken and moved by the less romantic aspects of exploration: the grit of the moon dust. This is a photograph taken after a significant event has occurred, post-climactic. I am often compelled by images of such after-moments, the almost forgotten underbelly of the “main attraction”. While the factual situation documented is anything but common (gunpowder-scented moon dirt clinging to skin, walking in space, probing into mysterious and dangerous territory), there is also something immensely accessible and intimate in this photograph. The simplicity of the moment is at once direct, calm, mundane and ephemeral.