ANNIKA ELISABETH VON HAUSSWOLF

The photograph balances between the familiar and the strange. I’m fascinated by how it’s clearly staged and arranged, yet I still read it as real. I believe in the image. Even though it’s obvious that I shouldn’t be able to, it still feels genuine. The image has influenced me in terms of how I want to create art. I also work with staging, and sometimes it works, while other times you just don’t believe it. That’s the beauty of this – you believe in it.

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff, It Takes a Long Time to Die, 2002, Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, The Fine Art Collections, © , Annika von Hausswolff

Afterimage by Hilma Hedin:

The first image that came to mind was Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s photograph: Det tar så lång tid att dö (It Takes So Long to Die). I was introduced to her work early in my career, right at the beginning when I started with photography. She had an exhibition recently at the Moderna Museet, and I got to see the photograph in person. I was just as moved by it as I was the first time I saw it.

What’s fascinating about it for me is how simple it is. This strange non-place, the gravel area she stands on. Her pants, worn at the knee as though she’s moved around a lot. Then the nice, clean sweater and her high heels – she looks good, also. And then she’s carrying this stone.

And the title – it’s so simple, almost banal, maybe even childish, but it speaks to a feeling I think everyone can relate to: the burden that living can be. There are so many relatable elements in the image, yet it’s so strange. Like the fact that she has her foot in a bucket and is carrying a stone – it almost becomes surreal.

The photograph balances between the familiar and the strange. I’m fascinated by how it’s clearly staged and arranged, yet I still read it as real. I believe in the image. Even though it’s obvious that I shouldn’t be able to, it still feels genuine. The image has influenced me in terms of how I want to create art. I also work with staging, and sometimes it works, while other times you just don’t believe it. That’s the beauty of this – you believe in it.

It feels as though she’s using her body to symbolize what it’s like to live. It’s a physical and overtly clear representation of the inner burden. She stands still with one foot in the bucket. She can’t move forward, it never ends. Perhaps that’s why it works so well as a photograph: it stops right there, it doesn’t give us before or after, just that moment. We just have to be in it. It goes on forever; we don’t see the end in this photograph. It’s cold around her, the gray, cold, dark surroundings, but it feels as though she’s protecting and guarding this stone. She carries it carefully, she holds onto it – it’s not something she’s ready to let go of.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream—much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

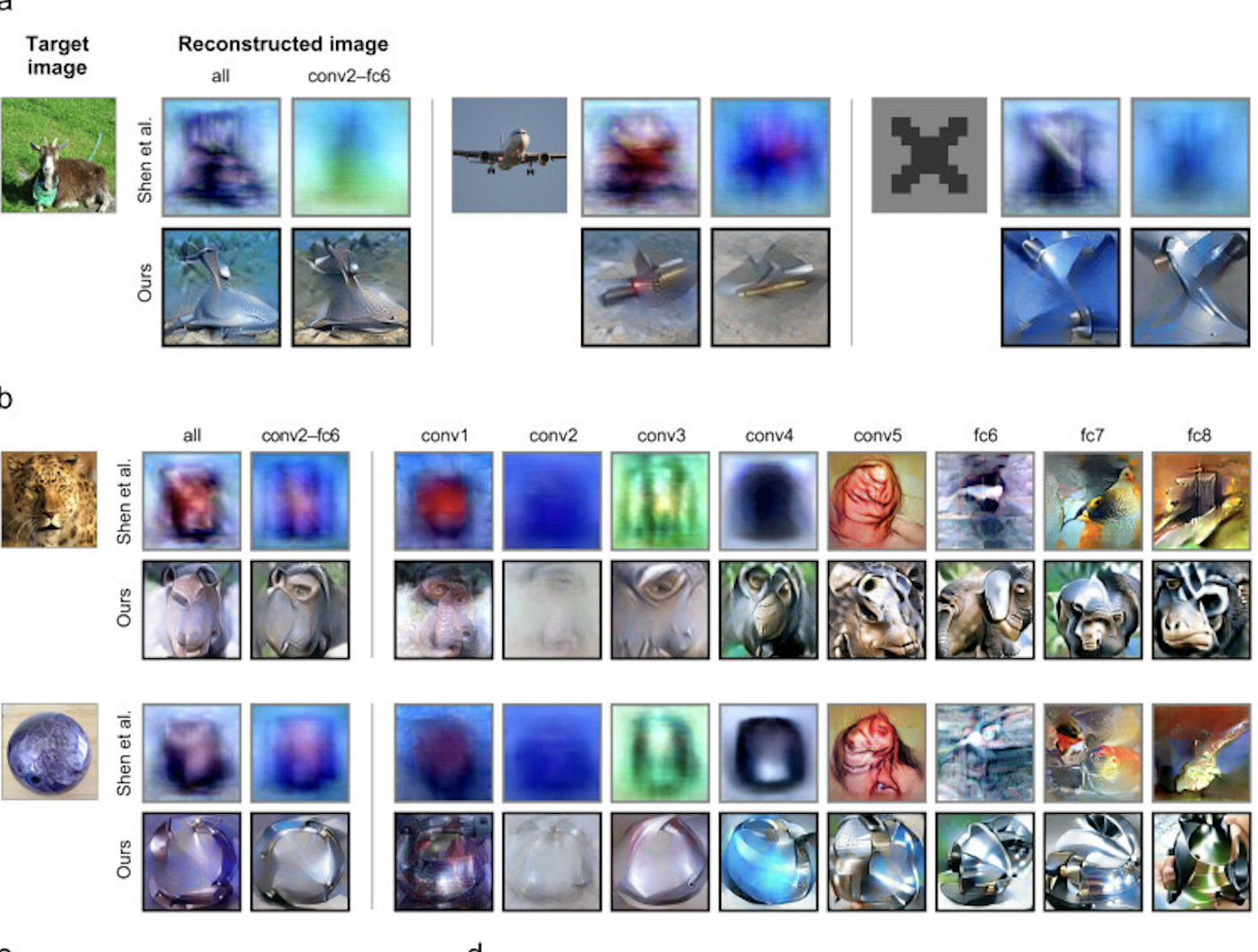

AGATHA WARA

I don’t have one specific image in mind, but the question made me think about the images we see with our mind's eye. I thought about something I recently learned—many people can’t actually see images when they close their eyes, a condition similar to those people who don’t have an internal dialogue; they don’t hear the ‘voice’ inside their head.

Image from Science Direct.

Afterimage by Agatha Wara:

I don’t have one specific image in mind, but the question made me think about the images we see with our mind's eye. I thought about something I recently learned—many people can’t actually see images when they close their eyes, a condition similar to those people who don’t have an internal dialogue; they don’t hear the ‘voice’ inside their head.

I wonder: how do these people process the world if they don’t see images in their heads? Do they relate things to experiences? Do they rather feel things?—maybe see a color, an or feel an emotion or some other sensation rather than visualizing the thing?

It’s also fascinating how, in the realm of modern science and technology, there now exist neuroimaging techniques that use AI to create visual representations of what we are looking at. In other words they can decipher the images we see in our minds.

In some ways it feels like our inner world is our last private space. Here, we can have thoughts that we can keep private, unknown to the outside world, unless we choose to reveal them. The development of neuroimagine technology makes me wonder how much longer we will have an inner world that is individual, just for the oneself, and private. In the future people may be forced to share their thoughts and inner images without consent. They will simply be hooked up to a machine and voilà !

In my work I think about blushing—when the face turns red from embarrassment—in relation to private and public space. Not everyone blushes, but those who do are tormented by it. They feel as if they are betrayed by the reddening of their face which reveals to the public what they feel inside: vulnerable. By blushing, one is forced by one's own body to make public an emotion that one would rather keep private and secret.

In order to survive, we’ve learned to hide our emotions. And while that’s sometimes a good thing—otherwise, we’d be walking around without any ‘skin,’ so to speak—it also highlights the tension between privacy and exposure. This idea has a dystopian quality, especially when we think about the future and how images and emotions may be accessed without our consent.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream—much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

ROLAND PENROSE

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of the gaze in photography. This particular image is especially interesting because it involves a refusal of the gaze. Each of the women has her eyes closed, yet their faces are very strategically positioned—almost in a diagonal line, tilted upwards toward the camera. It’s clear they’re aware of being photographed. Of course, it’s a posed image; I don’t believe for a second that they’re actually sleeping.

Roland Penrose, Four Women Asleep (Lee Miller, Adrienne Fidelin, Nusch Eluard, and Leonora Carrington, 1937). Print from color reversal film. © Roland Penrose Estate, England 2020. All rights reserved.

Afterimage by Clare Patrick:

I’m thinking about an image of four women sleeping. It was made in Cornwall in 1937, by Roland Penrose, and I first saw it earlier this year at the Met in New York. I was struck by how it ties into the surrealist fascination with dreaming and with closed eyes. This theme of dreaming has recurred in interesting ways over the past year, particularly now with the major surrealist exhibition here in Paris, for example. It continues to feel relevant.

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of the gaze in photography. This particular image is especially interesting because it involves a refusal of the gaze. Each of the women has her eyes closed, yet their faces are very strategically positioned—almost in a diagonal line, tilted upwards toward the camera. It’s clear they’re aware of being photographed. Of course, it’s a posed image; I don’t believe for a second that they’re actually sleeping.

It’s a very beautiful image, but it’s also a little unnerving. When I think of images that stick with me, they often do so because there’s something about them that troubles me in relation to photographic practice, or because they’re sentimental. Often, when I spend the most time reflecting on a photograph, it’s because the image ties into broader questions I have about the medium—its uses, its ethics, its craft, and the strategies people use to compose an image. This image pokes at questions of viewership, autonomy, and representation. I’m also very interested in the role of femininity within surrealism, and I think this image complicates that idea as well.

The women featured in the image are Lee Miller, Adrienne (Ady) Fidelin, Nusch Eluard, and Leonora Carrington. I’m currently researching Fidelin, and this was the first photograph of her I really encountered. Much of her history and narrative hasn’t yet been recorded, so it’s through photographs that I come to know her. This ongoing exploration of representation, autonomy, viewership, and subjecthood within photography is something I’m deeply interested in.

The image has many layers, particularly in a theoretical sense. As I spend more time with it, I think about the friendships, the intimacy, and the collaboration involved. Photography can be a space for collaboration, where the model or subject is as involved in the creation of the image as the photographer. So much of surrealist photography involves men taking photos of women, and it’s often been assumed that the relationship was one of muse and creator, with little collaboration. I believe it’s far more complex than that. And to start thinking about these relations differently can unearth so many more interesting possibilities.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

DIEZ & INSTAGRAM

Right now, Instagram is the news outlet we rely on to follow the live streams of political events, and I'm struck by its importance, and also still pondering some people's use of it. I'm still thinking about a post from Katherine Diez, a Danish writer and Instagram influencer who became famous for her carefully curated selfies, accompanied by reflections on literature and feminism. In 2018, she sparked controversy with a nude selfie in bed, holding a book she was reviewing, with the caption ‘Going to bed with my job.’ But it's the fairytale-like post from a hotel in Paris, where Diez lay in a large bathtub reading Le Monde, with a quote from Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar in the caption: 'Nothing can't be cured by a long, hot bath.' It was one of many beautiful photo-novels she shared.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Right now, Instagram is the news outlet we rely on to follow the live streams of political events, and I'm struck by its importance, and also still pondering some people's use of it. I'm still thinking about a post from Katherine Diez, a Danish writer and Instagram influencer who became famous for her carefully curated selfies, accompanied by reflections on literature and feminism. In 2018, she sparked controversy with a nude selfie in bed, holding a book she was reviewing, with the caption ‘Going to bed with my job.’ But it's the fairytale-like post from a hotel in Paris, where Diez lay in a large bathtub reading Le Monde, with a quote from Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar in the caption: 'Nothing can't be cured by a long, hot bath.' It was one of many beautiful photo-novels she shared.

Maintaining such a glamorous presence likely became a full-time job, but everything fell apart in January when Reddit users uncovered plagiarism in her reviews and Instagram posts. The criticism of Diez, was enormous, overshadowing scandals like the case of journalist Lasse Skytt, who plagiarized and even fabricated sources. Diez admitted to sloppy notes and missing citations, and soon after, she turned off the lights on her Instagram. Behind the scenes, it was revealed that she had signed a deal with People’s Press, and by October, a picture of the cover of her new book, I Egen Barm (In My Own Bosom), was posted.

The book reads more like an autobiography than a deeper analysis of her actions, with only a few pages devoted to the plagiarism itself. What remains is her strong need for validation. Diez might believe this personal backdrop explains her actions, feeling consumed by her role as a provocateur with a ‘fuck you all’ attitude. In her book Diez revealed intimate details about her relationship with Adam Price and other ex-boyfriends. The drama that has since unfolded between Diez and Price feels like a storyline from his TV series Borgen.

In an October interview on DR’s Genstart, Diez admitted she had lived in a different reality, always seeking recognition and not trusting that she was enough on her own. I’m still thinking about her meticulous planning of posts, she told the host about the one announcing her relationship with Price. She wanted to create an image of strength and invulnerability, with Price gazing off into the distance while she looked directly at the camera, as though signalling: ‘you can't reach us.’ As the host dryly pointed out, nothing about this image was left to chance.

Diez also writes about wanting to be an actress. The book itself could maybe be read as a performance, much like the platform that created her. She calls Instagram her theatre, but also her museum and playground. I think about another picture she posted with Price just weeks before everything fell apart, a picture he later removed from his profile. In it, he’s wearing an apron, leaning toward the camera holding a champagne bucket and a bottle under one arm, while pretending to taste a sauce from a pot in the other hand. It’s a peculiar pose. She stands beside him in an amazing dress, one hand leaning on the set table, a glass of white wine in the other. She’s in motion, her dress and stance reminding me of the dancing woman emoji in a red dress. She’s clearly dressed up—this is her stage. She had one dress for the photoshoot and another to move in for dinner. As I read further into the book looking for answers to why she plagiarised, this image begins to reveal itself. Although Diez doesn’t explicitly say so, the explanation might be the amount of effort she put into maintaining her curated platform.

Diez seems to have decorated her appearance just as she decorated her texts with the words of others. In one of the book’s brief chapters, she writes about how much she loves beauty. She points out that everything posted on social media, even the ‘imperfect’ moments, is curated. The word ‘imperfect,’ she writes, is the worst she knows. But is it not this striving for perfection, with our weaknesses always visible, that defines us all?

In a recent interview, Diez rhetorically asked, ‘How much more do you want?’ claiming she’d already delivered all her painful stories. All the ugliness. She doesn't know how to take any more responsibility for committing the same crime, which she believes has been committed by many before and alongside her, and says that she is certainly not the last to take other people's texts. From what she says, it seems that in her book, she confronts all her so-called imperfections. How I wish she could come to embrace these, seeing them not as flaws, but as part of the ongoing journey toward becoming better.

And now, after this appearance, Diez has slowly started posting again, in a carousel of images she writes that she has found herself again. I hope that's true. I'm thinking of something I read in a novel about ballet, that it's about pursuing perfection and also about pleasing, and how the protagonist didn't want that anymore, to pursue pleasingness. As Diane Arbus said, ‘There's a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can't avoid them knowing.’ Perhaps it's at this point - between perfection and imperfection - that Diez could have even more fun in her photo-novel life.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

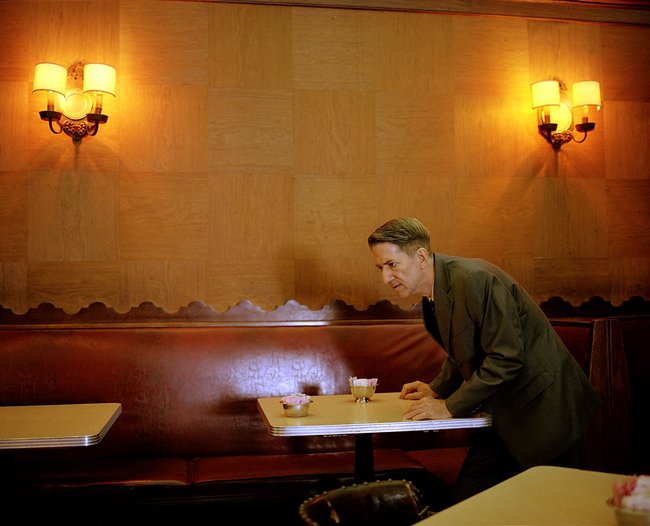

TOVA MOZARD

I quickly tire of images with a clear framework. Maybe it’s because I want to add my own story to the image—or at least leave room for that. I want there to be a form of communication between the image and the viewer, where my own experiences and associations also have space.

Afterimage by Max Barel:

Tova Mozart, Musso & Frank Grill, 2003

I quickly tire of images with a clear framework. Maybe it’s because I want to add my own story to the image—or at least leave room for that. I want there to be a form of communication between the image and the viewer, where my own experiences and associations also have space.

It was interesting to walk around the Grand Palais during Paris Photo. Perhaps mostly because I realised how much I’m unable to be captivated by. As if there’s so much I don’t understand or can’t quite connect with. And where does one’s gaze even come from? Is there a distinct Nordic style, with its own ideas of what works or doesn’t? It was a valuable exercise in trying to look beyond the image itself, beyond the initial response.

I first saw this image a couple of years ago, as a student at HDK-Valand in Gothenburg. At first, it was his hands that caught my attention. Piano fingers, the half-closed gesture, and how they rest on the tabletop—both tense and relaxed. There’s something fragile about them. Then there’s his face. I’m drawn to it, both positively and negatively. I feel a lack of trust in him, almost disgust. His ambiguous gaze and body position—he’s both about to stand up and sit down—create a tension. There’s both calm and noise in the image, a look that’s both distant and determined.

He’s in a transitional phase, caught in an unnatural movement. I think of all the movements we see around us that we don’t have time to notice. In this way, photography is unique: it captures a brief glimpse of something that would normally be out of reach. Many photographers work with similar stagings, and I think a common denominator for the images I enjoy is that they simultaneously depict something staged and something real—a moment captured.

I also keep returning to the themes of playfulness and simplicity. How the cornice at the top of the image isn’t straight, and how I often strive to create straight lines and controlled compositions in my own work. Yet many good images have a crookedness, an imperfection to them. At least in an image like this, with so few elements. An empty restaurant, a few tables, a leather sofa, two lamps, a paneled wall. A pleasant room to be in, yet you can’t avoid the violence he radiates.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

LAURE PROUVOST

There is a newsletter. Laure Provoust opens a big new show. My day (and my soul) is slowly sinking and the accompanying photo lifts me up, it makes me smile. Breasts like eyes and head. Lots of tentacles, one even giving a thumbs up as if to signal that this is all going to work out, the rest holding water and a cup and other things. Some are just hanging there, ready to work. It makes me think of something Aretha Franklin said when asked what her biggest challenges in life were. I am pretty sure the journalist did not expect her to answer that the hardest thing was figuring out what to make for dinner every day. Although I am a long way from being Franklin, I feel very connected to this octopus who holds on to important things.

Laure Prouvost, This Means, 2019. Glass, nailbrush, steel, pump, water, 203 x 180 x 180 cm. Courtesy of the artist and carlier / gebauer, Berlin/Madrid. Photo: Trevor Good, carlier / gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There is a newsletter. Laure Provoust opens a major new show. My day (and my soul) is slowly sinking and the accompanying photo lifts me up, it makes me smile. Breasts like eyes and head. Lots of tentacles, one even giving a thumbs up, as if to signal that it will all work out, the rest holding water and a cup and other stuff. Some are just hanging there, ready to work. I am reminded of something Aretha Franklin said when asked about her greatest challenges in life. I am pretty sure the journalist did not expect her to reply that the hardest thing was deciding what to make for her children's dinner every day. Although I am a long way from being Franklin, I feel very much like that octopus holding on to important things.

‘We must keep our energy,' my friend says, or rather shouts at me, as we are in the noisiest hour of the day for the bar. When I arrived, the waiter scolded me for not saying bonjour before asking for a table. He was right, I was very tired, it's been a year this week since Tuesday when the misogynist was re-elected. Is this a test, are they letting him try again to see if he can do something good? I wonder if he appreciates being treated fairly, with none of his opponents shouting that the election was rigged.

My friend and I both long to live in two cities. I tell her about a still I’ve just seen on Instagram, from a film where the subtitles read: ‘All my life I've felt like I've been in two places at once. Here and somewhere else.’ It's the week of the photo fair in this city, and after all the images I've seen at this year's very spacious and splendid edition, and also on the boat of books, this is what remains in my mind. My friend wonders why these stills don’t pop up in her feed. In hers it is as if Princess Diana and Whitney Houston are still alive, they are in almost every post she sees.

She says she is staying in Paris for now. No need to go where the madman is taking over again. The music is back to normal, so are the shoulders of the angry waiter, many have left for dinner and we can spread out more. I tell her she's right, we need to conserve our energy. A year into a catastrophic war and with this unknown uncertainty unfolding. We didn't order wine, just citron chaud for the vitamins. As I leave, I make sure to wish the waiter a bonne soirée and also bon courage, because I think he, and we all, will need it.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

ALAA HAMOUDA

Despite the constant wave of visual and written information we receive every day, there's one video I've been thinking about since it came out. It's of two Palestinian siblings, Qamar and Sumaya Subuh, released by the Al Jazeera network. We see a journalist meeting these two young children, one carrying the other. The journalist asks them what has happened and where they are going. It turns out that one of them was hit by a car. They say they are on their way to the Bureij refugee camp or just anywhere that can help. The journalist decides to help and drives them to Bureij, where one of them carries the other. Then the clip ends. Of all the videos I've seen, this is the one I play over and over in my head.

Afterimage by Sunniva Hestenes:

Screenshot from Al Jazeera’s Instagram. Images of the two sisters were captured by Palestinian journalist Alaa Hamouda.

Despite the constant wave of visual and written information we receive every day, there's one video I've been thinking about since it came out. It's of two Palestinian siblings, Qamar and Sumaya Subuh, released by the Al Jazeera network. We see a journalist meeting these two young children, one carrying the other. The journalist asks them what has happened and where they are going. It turns out that one of them was hit by a car. They say they are on their way to the Bureij refugee camp or just anywhere that can help. The journalist decides to help and drives them to Bureij, where one of them carries the other. Then the clip ends. Of all the videos I've seen, this is the one I play over and over in my head.

I think it's because of the way it's filmed. It feels close, almost like I'm standing in the journalist's shoes. I look the children straight in the eye, they look at the journalist and the phone in his hand (me). I think about their gaze, how it is absent and present at the same time. I know that such a look can only come from one thing, and that is cruelty. At the same time, I know that I will never understand how bad it really is. The video's powerlessness haunts me. My own, Sumaya's and Qamar's. It could have been me. And it's a truth that is so extremely frightening, also in relation to the fact that there are so many who choose to look the other way.

It's about empathy and positioning. If we can place our experience in what we see, it's easier to recognize. This applies to everything - dreams, reality, relationships and possessions. The more willing we are to relate to something, the easier it is to engage, participate, and share. I think of the duality that exists in constantly witnessing what the Palestinian people are going through without really understanding, physically or mentally, the level of damage you are witnessing. The same goes for Congo, Lebanon and Sudan. All through the telephone, which both communicates and protects.

Still, refusing to witness the atrocities you see is the same as saying it's okay in my worldview; I can't vouch for it. You can't look away. You have to do something.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

DUY NGUYEN

As a photographer, I often think about the pictures I can't take. We live in a world where almost everything is documented, especially with the internet and social media. Everything is instantly shared and broadcast, especially in these turbulent times of war, genocide and more. It almost feels like nothing is off limits to be documented. I often feel that my brain and emotions are not built to consume it all at the current rate.

Afterimage by Duy Nguyen:

As a photographer, I often think about the pictures I can't take. We live in a world where almost everything is documented, especially with the internet and social media. Everything is instantly shared and broadcast, especially in these turbulent times of war, genocide and more. It almost feels like nothing is off limits to be documented. I often feel that my brain and emotions are not built to consume it all at the current rate.

Like many others, I'm often looking for a way to escape the real world and our documented reality. One place of refuge for me has been club culture, and as I live in Berlin, one of my most frequented clubs is Berghain/Panorama Bar. A place where I often meet people from different backgrounds, sexual orientations, gender identities, ethnicities and so on.

Not long ago I was there with two friends visiting from Norway. Taking a break from the sweaty dance floor, we found ourselves standing against a wall facing a group of sofas where clubbers come to smoke, rest and chat. The room was filled with all sorts of almost naked bodies piled on top of each other, lightly covered in cigarette smoke. As different coloured lights fell from the ceiling on each of them, it really did look like a grimy version of a Renaissance painting. At that moment I wanted to take a picture. Of course, I knew I couldn't, because that would defeat the purpose of being in a place where you can escape and no one can document you. Instead, it became a mental image for me and my friends as we stood there, archiving time. I suppose when you know you're not being recorded you can be more yourself. Or at least a version of yourself that you can't be in a documented reality.

A space is just walls (physical or not) - and what everyone brings to it makes up the space. In Berghain, we all agree that the experience shouldn't be documented, and that's part of what makes it special. Maybe you see better when you can't photograph it, or maybe you see beyond your eyes when you're not just looking through a lens. In any space, you get what you give. That night, I gave everything I had on the dance floor. When my legs couldn't take me any more, I left those walls feeling inspired by the pictures I couldn't take.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

HODA AFSHAR

When you asked me to choose just one image, it was difficult. I see so many images all the time—especially through social media—that my mind feels both full and empty at the same time. But there's one image I've only encountered on social media that has stuck with me. Every time I see it, I feel compelled to linger on it and return to it, both visually and because of its content.

Afterimage by Marie Sjøvold:

Hoda Afshar, In Turn, 2023.

When you asked me to choose just one image, it was difficult. I see so many images all the time, especially through social media, that my mind feels both full and empty at the same time. But there's one image I've only encountered on social media that has stuck with me. Every time I see it, I feel compelled to linger on it and return to it, both visually and because of its content.

In my memory, I had merged two of the photographer's images. One depicts three women braiding each other's hair, and the other shows a woman holding another's braid. Somehow, in my mind, they've fused into a single image. It's fascinating how our memory can absorb so many images that they blur and transform into something new.

Without knowing anything about the photographer or the context of the work, my initial associations were with my own childhood. I remembered a scene from Anne + Jørgen = Sant, where one girl cuts off another's braid—an incredibly dramatic moment. There was something so vulnerable about the braid being held. Hair carries many associations: it's free, intimate, and personal, often tied to identity. Cutting hair can feel like severing part of your own history.

There was something subtle yet political about the image for me, and upon closer inspection, I learned more about the Iranian photographer Afshar and the image's explicit political context, which made it even more powerful. It's stayed with me for so long because of that. The image's visual simplicity and poetic nature become even more impactful when you understand it's connected to the feminist uprising in Iran in 2022, following the death of Mahsa Jina Amini. That connection to real-world events makes you reflect on your own life and privileges.

What makes this picture so incredible is how it captures a moment of solidarity with such a powerful, political message, yet still resonates with something deeply personal that I believe everyone can relate to. It's an impressive fusion of the political and the personal.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

NONA FAUSTINE AND JULIANA HUXTABLE

I had a lot of options in my head, there's so much good stuff out there that I think about a lot. One of the first images that came to mind was from Nona Faustine's White Shoes series. I saw the series in New York at Easter and the artist took pictures, in different versions of nudity and with white shoes, of different places in New York City where there was a slave trade or places where black people were not allowed to be.

Nona Faustine, from the White Shoes series. They Tagged the Land with Trophies and Institutions from Their Rapes and Conquests, Tweed Courthouse, NYC, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Higher Pictures. © Nona Faustine

Afterimage(s) by Lisa Bernhoft-Sjødin:

I had a lot of options in my head, there's so much good stuff out there that I think about a lot. One of the first images that came to mind was from Nona Faustine's White Shoes series. I saw the series in New York at Easter and the artist took pictures, in different versions of nudity and with white shoes, of different places in New York City where there was a slave trade or places where black people were not allowed to be.

There's a particular image in that series where you see Faustine pushing a column, completely naked, in these white shoes, you can see that she's exerting herself, that it's exhausting. I've been thinking a lot about this exhibition, and I thought that's something I should continue to think about, in relation to who I am and where I'm going. And in relation to the issues that are going on in the world. It visualizes what these people have experienced in the generations before us.

Juliana Huxtable, Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm), 2015

And I realized that I'm really interested in that, and what it's like to cross boundaries between what's human and what's not, and then become a hybrid or a myth, and then I came to a work that I keep coming back to, by Juliana Huxtable. I love everything she does, but there's one self-portrait in particular that I saw during the triennial at the New Museum in 2015. Untitled in the Rage, Nibiru Cataclysm shows the artist sitting with a background of clouds, and behind her you can see a planet that looks like a moon. Her body is green and her hair is yellow. I feel that there are three things that this painting represents to me.

First, it's what the Nibiru cataclysm means, the myth of a ninth planet in the solar system that threatens to crash into the Earth and destroy everything. Which Huxtable then mythologizes as this cataclysm that comes and blows up everything about identity, trans identity and feminism. And about freedom and unfreedom within that theme. The second is how the portrait circumvents what a self-portrait is. The image has so much to say about who Huxtable is, the image for me has an effect where it breaks absolutely all boundaries of what it means to identify as something.

The last part is about how you think about where you're going in terms of feminism and identity politics. Because what's interesting about Huxtable-and this particular portrait-is that it points to a place where we're going in terms of identity politics and feminism in the future. We often talk about what's happening now and what's happened. What we want to fight against and what we can achieve in the future. And if you drag the past into the future, you're kind of stuck, you're so quickly influenced by the past that the future becomes impossible to imagine. That's where Huxtable comes in as Cataclysm and helps with that. Her starting point is what she wants the future to look like. And that's why that image stuck with me, because it felt completely eye-opening.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

NICK WAPLINGTON

It’s funny to think back on the photographs that meant a lot to me when I was younger. Not just as a nostalgic reminiscence, but as a way to understand and remember what I saw and liked in them, compared to what I see today. I remember being five years old or so, and loving the photographs by Nick Waplington. Their plush, synthetic surfaces stood out to me. I think of families eating ice cream in rooms with carpeted floors and patent-leather sofas in different shades of pink. The drama and chaos and abundance of people and stuff—which I have now come to see as the images of struggling British working-class homes in the 90s—filled me at the time with an unsettled combination of envy and fascination.

Afterimage by Emma Aars:

Nick Waplington, image from the book Living Room, Aperture, 1991.

It’s funny to think back on the photographs that meant a lot to me when I was younger. Not just as a nostalgic reminiscence, but as a way to understand and remember what I saw and liked in them, compared to what I see today. I remember being five years old or so, and loving the photographs by Nick Waplington. Their plush, synthetic surfaces stood out to me. I think of families eating ice cream in rooms with carpeted floors and patent-leather sofas in different shades of pink. The drama and chaos and abundance of people and stuff—which I have now come to see as the images of struggling British working-class homes in the 90s—filled me at the time with an unsettled combination of envy and fascination. I didn’t notice the cigarette butts on the floor, the stains everywhere, how everything was covered in a shade of dirt, or see the fights as real fights. I saw the girly dresses, soft tracksuits and plastic toys I never got. Waplington’s photos captured everything I felt my own life lacked. I can still recall my obsession with the young girl in a tartan dress trying to cut the lawn with a vacuum cleaner. There was always so much happening, and it always seemed to be so much fun.

A girl in her early teens, leans against the floral wallpaper. An older girl sits on a sofa to her left, along with others who are beyond the frame, while to her right, two younger children attempt to strangle each other. A mother with a pair of infants on her lap and a troubled face speaks to someone in the room from deep down in her red velvet armchair. Our girl has red-brown hair and a sharp face, and her hands are in the pockets of her way too big pink sweatpants, pulled up at the ankles, showing her dirty white sneakers on the wine red carpeted floor. She watches her family from a distance, as if she were the photographer—not indifferent, but reclusive in a sense. She acknowledges, but she does not participate. She is a grounding element amongst the chaos in the image. There is a self-consciousness underneath it all. Some are looking at themselves being looked at.

This text is taken from the essay Eye as a Camera, Objektiv #28. Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

RAGNHILD AAMÅS

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

Afterimage by Ragnhild Aamås:

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

I thought I was beyond the effects of them, the images. We live in far too interesting times. But this one hits my inbox, in a newsletter from a newspaper I follow. I register it in my side-view while I'm working on a wooden figure.

It is not, I think, the aesthetics of the image, its sensuous reach, that strikes me, nor the indignation of the suffering, but rather a mimetic response that lands like a fist. A child sitting on her mother's lap, with a calm, almost angelic face. She looks the same age as my daughter EY. Like any other child, she is quite content to be on a parent's lap, regardless. The mother is hunched over, her face distorted by muscle and emotion, far from calm. Around her, women and children sit on the dusty floor, their wounds treated in various ways. In the background: a rubbish bin with a black bag, a plastic tube sticking out, empty packaging for bottled water, a five-litre container of some liquid in front of it, protected by cardboard. There is familiar street wear, dust-covered black backpacks on the floor, several darkened reflective surfaces of depowered screens. A bald man, propped up halfway between wall and floor, with bloody cotton swabs on his head, clutches a mobile phone, his face an empty field. As a group in a setting, they conform to what Susan Sontag quotes as Leonardo Da Vinci's instructions for showing the horror in a battle painting:

Make the defeated pale, with their eyebrows raised and knit, and the skin over their eyebrows furrowed with pain ... and the teeth apart as if crying out in lamentation ... Let the dead be partly or wholly covered with dust ... and let the blood be seen by its colour, flowing in a sinuous stream from the body to the dust (Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003).

I wonder if they have consented to have their pictures taken. I wonder in whose feeds the picture will appear, and with what caption.

Wait, there is something nestling in the stillness of the child's face: a quiet place, a silence, a projection beyond

Has motherhood, parenthood, the carrying of responsibility, rekindled in me a certain need to no longer ignore politics? Or let's put it this way: it seems to have attuned me to the fragility of things, to the integrity of the body, and to a certain stickiness of time (EY, who I'm calling as I type, has been intruding on me since she came home from kindergarten on the third day with an eye infection – and we have sterile saline water). There is a feeling of being turned upside down, but this is balanced by obligations of care, in the sense of Juliana Spahr, a micro-dose of contempt for the ethnostates and the ongoing governance of death.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag points out that suffering is always at a distance; in a sense, we can never be close enough. In the confrontation with images, there remains a central potential for empathy. But it is not independent of narrative and the ability to place oneself in the privileged position of having distance from immediate suffering, from the unfolding hierarchy in which the damage is received and captured.

Who is not in the picture? What is not depicted? What subject is not as easily captured as suffering? Could I imagine that the eyes of the child, who is certainly not looking at the lens, are staring at something beyond, at something responsible, at the ideology of nation states? Not somewhere else, but here.

Image: Aamås’ screenshot from inbox of newsletter showing photo by Mohammad Abu Elsebah / DPA / NTB). Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

SPARE RIB

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know. Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor.

Afterimage by Nina Mauno Schjønsby:

Certain Shadowy Parts

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know.

Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor. Written by women and focused on women's issues, the magazine addressed topics such as domestic violence, women’s mental and physical health, and the lack of equality in education and work. It was founded by two English women, Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott, in 1972. They were soon joined by others, among them Irish Roisin Boyd and Nigerian Linda Bellos.

One of the reasons why this image resonates with me, may be that it stands in for countless others that were never taken or published, images of other independent editorial teams emerging from marginalized or suppressed positions. Spare Rib, along with many feminist magazines both before and after, shows how people can create a space together – a micro-public – where they define what should be said and how. For me, this photograph represents the feminist community necessary to produce such a magazine. It also illustrates the solidarity, even in the midst of the disagreements that I know existed among them.

Today, Spare Rib has successors such as the London-based zine OOMK, which focuses on Muslim women, Belgium's Girls Like Us and Norway's Fett.

Editorial processes and the various stages of creative work are often invisible. Once a magazine has gone to press, its history closes in on itself. Perhaps this has always been the case. In my book Gi meg alt hva du kan (2024), I write about how, in the 1830s, Camilla Collett and her friend Emilie Diriks taught each other to write and explored the conditions of their lives through an intense correspondence. Their collaboration culminated in the handwritten magazine, which they called Forloren Skildpadde. In this way, two young women created their own intellectual space. This is Norway's first feminist magazine and an early forerunner of feminist publications such as Spare Rib.

I am fascinated by how, through intimate conversation and close collaboration, something bigger than oneself can emerge. Zines, magazines and small press publications still give a voice to marginalized perspectives and shed light on issues that might otherwise remain in the shadows – what Camilla Collett once called "certain shadowy parts.”

And there they sit, the editorial team of Spare Rib, the magazine that would survive until 1993, despite editorial disagreements and financial constraints. They occupy a place between a private sphere – their editorial office – and a public sphere – the street outside. For me, this image symbolizes how an intimate dialogue between friends or colleagues can be the beginning of something much larger: a multifaceted conversation that eventually turns outwards into the public sphere, branching out and reaching us even now.

TUNGA

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond. I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village.

Performance of Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós at Fundição Progresso, Rio de Janeiro 1987. Courtesy Wilton Montenegro and Instituto Tunga

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond.

I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village. The image is striking, impossible to miss - two young girls, in their teens, looking at each other, holding their long, shared hair in their hands. I can see their profiles, their noses. Why are they still together? They could let go.

I walk past a poster with a quote from Coco Chanel: ‘A woman who cuts her hair is about to change her life.’ I think of another friend who bleached his hair and claimed it would change everything. I wonder if it did.

Later, in a café, I search for more information about the twins and come across a description where the artist references a mythical text attributed to a Danish naturalist. As I scroll further, I learn that the conjoined twins were sacrificed upon reaching puberty, and that when a woman began to embroider with hair taken from them, it turned to metal and became gold.

On view in GROW IT, SHOW IT! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok at Museum Folkwang, Germany.

ELSE MARIE HAGEN

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's annual exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind...

Else Marie Hagen, Stilleben, 2023.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's Autumn Exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... The work was made after the artist repeatedly met a woman on a bus who 'looked deep into my eyes for a few seconds and down into my shoes.’

There is also Serina Erfjord's embroidered work from Dr Mahmoud Abu Nujaila's photograph of the last message on the notice board at Al Awda Hospital in Gaza: 'Whoever stays until the end will tell the story. We did what we could. Remember us.’ Or the phone call between Israa Mahameed and her mother, between Norway and Palestine, in A Random 13 Minutes, both keeping the conversation going amidst the terrible sounds from outside the mother's house.

These three works leave this writer in a certain state in the encounter with Hagen's still life. A photograph of the currently deaf and blind puppy trying to orient itself on the desk by the window where someone left it. Around it, a random clutter, which Hagen writes: ‘can be associated with a young person who might have something in common with the puppy.’

For what do we do, what can we do, the people inside in Gaza could see us as blind and deaf as this animal. They have every right to feel abandoned, nothing has changed in these past eleven months. The annual autumn exhibition aims to be a challenge by showing contemporary art, writing that: ‘Anything that shakes our sense of security seems provocative. Contemporary art is often such an unexpected encounter.’

When I look at this work, I'm reminded of a colleague's answer to his daughter's question about what he did in his studio all day. He said that sometimes he looked at a photograph he'd been making for a long time. When she asked him why, he said that for him the picture could work as a question mark, something for others to figure out, like this animal trying to understand the world. And then, if it really works in a provocative way, it can become something more, something bigger, something that can help change things. Like Hagen's. Possibly.

ROMANE BLADOU

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about. I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay.

Moving a house in Trinity Bay. Ca 1968. From the Collection: Resettlement Photographs, Maritime History Archive.

Afterimage by Romane Bladou:

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about.

I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay. It's being pulled by some small boats towards the hills in the background. And it was taken at a time when there was a policy of relocation, of resettlement within the province. People who lived in very remote places, in isolated parts of the Canadian coast, were asked, forced in a way, to leave their homes and peninsulas in order to move to places where there were jobs, hospitals and services. And they did this by floating their houses across the bay. The image stuck in my head. I had no idea you could do that. And it also felt so poetic. It was just this house floating to somewhere else. And I kept thinking that they would be living in the same home they had lived in all their lives, walking on the same floors, but with a completely different view outside the window every day. Even the light in the house would be different. Maybe they could see from the window where they used to live. I don't know.

In a way, I think what resonated with me is also this relationship to home, especially as an artist, we're always travelling. Maybe this image acts as a metaphor – it is about this desire to be anchored and grounded somewhere, but at the same time this constant pull to go to other places. So it's always in my head, I guess. In a different context, I wish I had a floating house.

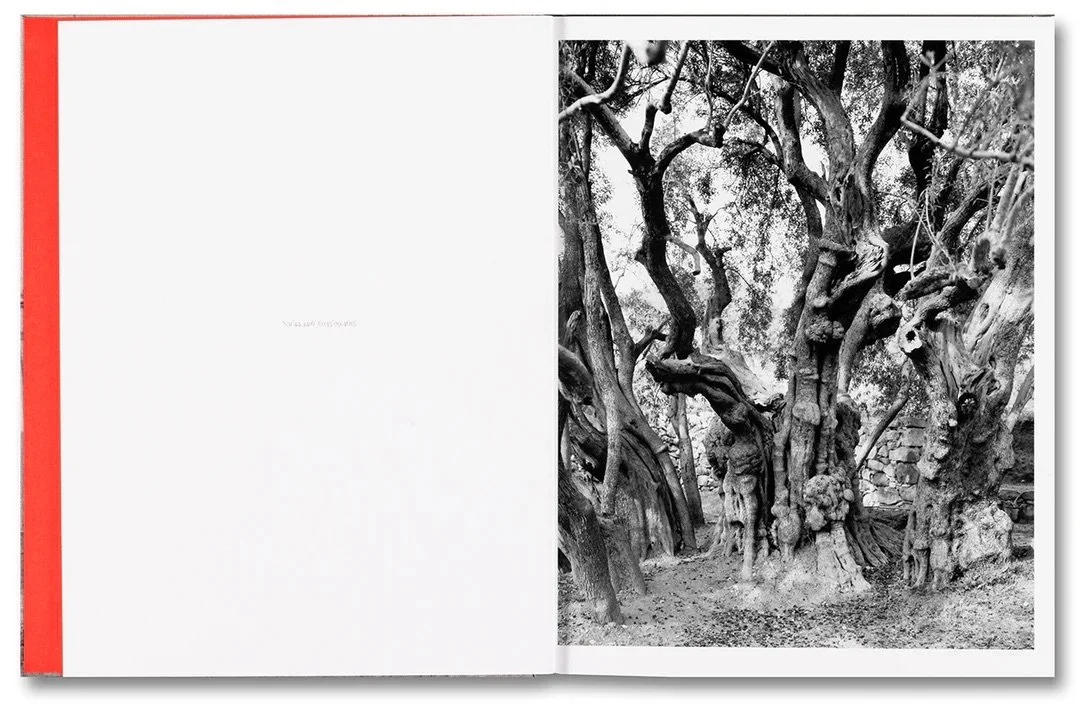

ADAM BROOMBERG & RAFAEL GONZALEZ

What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

Afterimage(book) by Nina Strand:

We share posts in solidarity. We sign campaigns. We go to marches because doing nothing is not an option while this goes on. Today, I see a young couple who look as if they’ve just stepped out of a Woodstock film: long hair, loose clothes, seemingly free spirits. They stand close together. While a politician speaks into the makeshift microphone—no one can hear her—I continue to watch them. His moustache is like Salvador Dalí’s, his shirt is tie-dyed, he’s one hundred percent in character. I've seen him before, at another demonstration, but with a different girl. Is this how he dates, by proposing to meet at a demonstration? In any case, it’s for a good cause. I'm so fascinated that when the rally is over, I follow them into a café and find a table nearby.

In my bag I have the book Anchor in the Landscape by Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez: black and white photographs of trees in the Occupied Territories of Palestine. Each page has a photograph on the right and the geographical location on the left. A sentence about the book haunts me. Since 1967, 800,000 Palestinian olive trees have been destroyed by Israeli authorities and settlers. Eight hundred thousand trees... I read about olive trees. They grow slowly.

I overhear the moustache say that he used to cry when everyone shouted 'Let the children live' at the demonstrations for Palestine. Now he's worried about not shedding a tear. Has he become numb? The number of dead and missing Palestinians is unimaginable. I hear them talking about a friend who does nothing, no posts shared, no signatures. What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

When the woman tells her date that she struggles with sharing images of dead people, I almost join them at the table in agreement. I still worry about what it does to us to see them. I understand what a colleague said to me, that the Palestinian people want us to share, want us to see and understand. I share everything except pictures of lifeless bodies. When I wrote a post asking those with children to think about what they post, she told me off: ‘Who am I to decide?’, she wrote. I’m still not sure if she’s right. But I wonder more about those who do not share. I believe in doing something.

I actually got the date for today's demonstration wrong. I went to the square yesterday. It was just me and a Palestinian flag that someone had left behind. I spent some time there. Alone. Saying ‘Free, free Palestine’ several times. When I pass it on my way home, the flag is still there.

YOKO ONO

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Yoko Ono, installation view of Bag Piece, 1964, in “YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND” at Tate Modern, London, 2024. Photo © Tate (Reece Straw). Courtesy of Tate Modern.

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

There is a small statement next to the bag piece where the artist explains that you can see the world from it and talks about how when you are in a bag you become just a spirit or a soul, everything about race, age and gender falls away. The man in the bag sits very still, he might wonder where his girlfriend went, I see her looking more closely at the instructions on how to make a painting for the wind at the wall opposite.

After a while, the man emerges from the bag and shakes it a little before folding it neatly and handing it back to the museum assistant. That last gesture was like a more genuine performance my friend says.

We discuss trying it on, and I look back at the film, just as the same person cutting a hole in the bust is busy cutting off the bra. The film ends where the artist covering her breasts with her hands. It is shot in black and white, I wonder if she is blushing. It will still be me in the bag. There is no possibility of an escape. I suggest we move on.

JOAN JONAS

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

JOAN JONAS. Jones Beach Piece mirror on ladder, 1970, printed 2019. Photographed by Richard Landry. (The image found at Gladstone Gallery.)

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Being like Pippi Longstocking is no bad thing: her motto was, 'I've never tried this before, so I think I should be able to do it,' and this applies to so much of Jonas's pioneering work in video and performance. Later, in the museum shop, we see Jonas with her cane and dog in tow, here to give a talk. ‘What a fantastic show!’ I say to her in passing; she thanks me and moves on quickly, but that’s enough for me: just to see the woman who, according to the text on the museum's website, ‘began her career in New York's vibrant downtown art scene of the 1960s and 70s.’

I thought a lot about solidarity, generosity and a sense of community after seeing the show, and wonder where to find this today. Another colleague told me that he had visited Louise Bourgeois in New York, in her home, for one of her Sunday salons where she invited young artists. I thought of this, and of Jonas, when I later visited the exhibition Forks and Spoons at Galerie Buchholz, curated by Moyra Davey, where she weaves her stories and thoughts about each artist into the film that opens the show before we see the photographs. I wondered if I could find some of the old art scene spirit by visiting Francesca Woodman’s apartment in Tribeca. I learned from the film that Betsy, her old flatmate, still lives there, now with her 21-year-old daughter, in what she has jokingly called Grey Gardens. And another photograph, New York, New York, from 1977, by Alix Cléo Roubaud has some of Jonas’ playfulness: a big white canvas with a picture at the top of a small group of people in the park.

I'm thinking about what the strict customs officer asked me when I landed: ‘Are you here on business?’ and I said ‘Yes,’ but then his forehead wrinkled and I was worried mentioning anything about work might lead to not being accepted, so I blurted out: ‘Well, I'm an artist, here for the Art Book Fair. I'm not sure if a visit made by an artist with no money would qualify as a business trip?’ He didn’t find it funny and I should know better than to make a joke. But I could tell him now that this trip has made me very rich indeed.

LUCAS BLALOCK

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written.

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written. It kind of stopped me flat, and made me think about this time of immense shift and how the ascendency of photography had changed the world. It recontextualized what I was doing with a camera and tied it more deeply in to other structures—my experience as an American, and as my parents’ kid—and I thought maybe I’d been thinking about this photography thing all wrong, giving it short shrift, not taking as seriously as I might its contribution to our fundamental condition.

I am ‘here’ because it became undeniably evident to me that photography has been a central player in the world since then. Vilhelm Flusser writes in Towards a Philosophy of Photography that there are only two real turning points in human history— the invention of linear language, the basic building block of historical understanding, in the second century and the invention of the technical image, which mystifies historical thinking, in 1839. Photography has become a, if not the, lingua franca of the world I live in. The invention of photography and The Whale marked similar transitions into the modern. Ishmael’s world and ours became very different by the time they were done.

From Why must the mounted messenger be mounted? by Lucas Blalock. Order it here.