SHAHRZAD MALEKIAN

This is my pop-up sculpture and installation in public spaces. It operates at the intersection of the natural and the human-made. Plants, moss and fungi become entangled with the body of the sculpture and creating a continuously evolving and living sculptural form. For me, this is a perfect symbol for the current situation which is happening around the world, and my contribution to this series. I want to remind the audience of the urgency of rethinking our relationship with non-human forms of living.

ESSI KAUSALAINEN

Dear L,

While writing this, the early spring light filters through a thick layer of clouds and bounces from the snow covered roofs. The light is so even there are nearly no shadows visible. Somehow this makes sense with my sense of time, which has gone out of joint. The days are short and long with no apparent logic. They are thick, sticky and viscous, and my attempts to organize them into segments of activity and rest seem to be ridiculed. All the borders grow soft and blurry.

I am filling this uneven time by walking in circles in the suddenly quiet seaside city, orbiting like a moon of an unknown planet. Everything is floating. My body, the time, the language. In my solitude I am knitting new words to tell you how it all resonates in me: the sense of pressure within the bone, the electricity behind the eyes, the opening of the skin in my back that allows the room, the world, to flow through.

In these peculiar settings, I have started to sew. Connecting pieces of fabrics into shapes, into platforms for unknown future events. Most of them are so small and light one can carry them in a pocket. Yet, they are all big enough for two people to stand on, if their bodies are arranged close to each others. I hope one of these days I could orbit to you and hand one over.

With love, E

(This text has not been edited by Objektiv as it is a personal letter.)

PATRICIA CAROLINA

In my practice as an artist, these short clips function as letters in an upgrowing alphabet.

VILDE SALHUS RØED

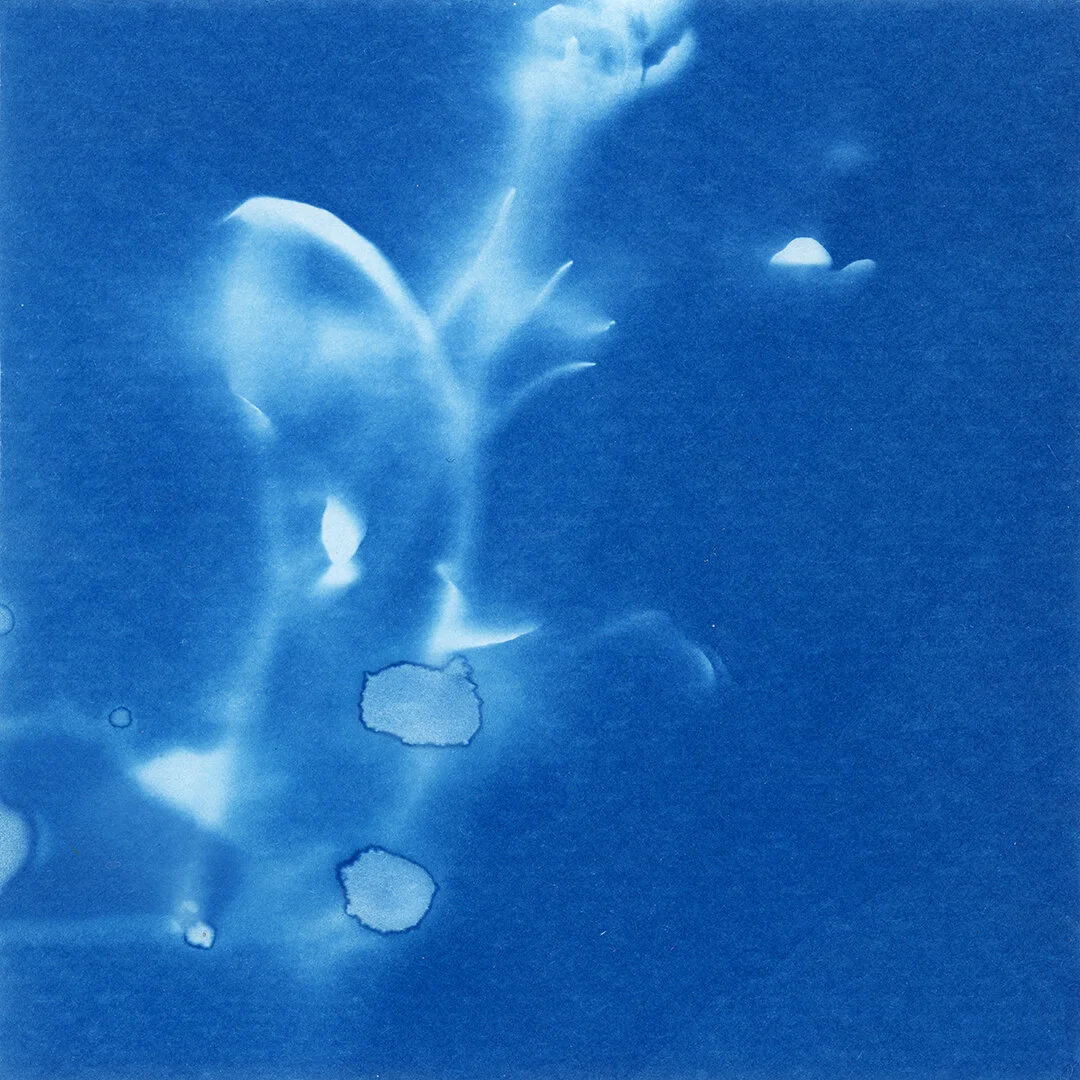

The Same Sun

Sun prints from hikes in mountains not far away, but closer to the sun, together with Una 4 1/2 years old, in the early spring of 2020, when time and days began to flow.

ANDREA GRUNDT JOHNS

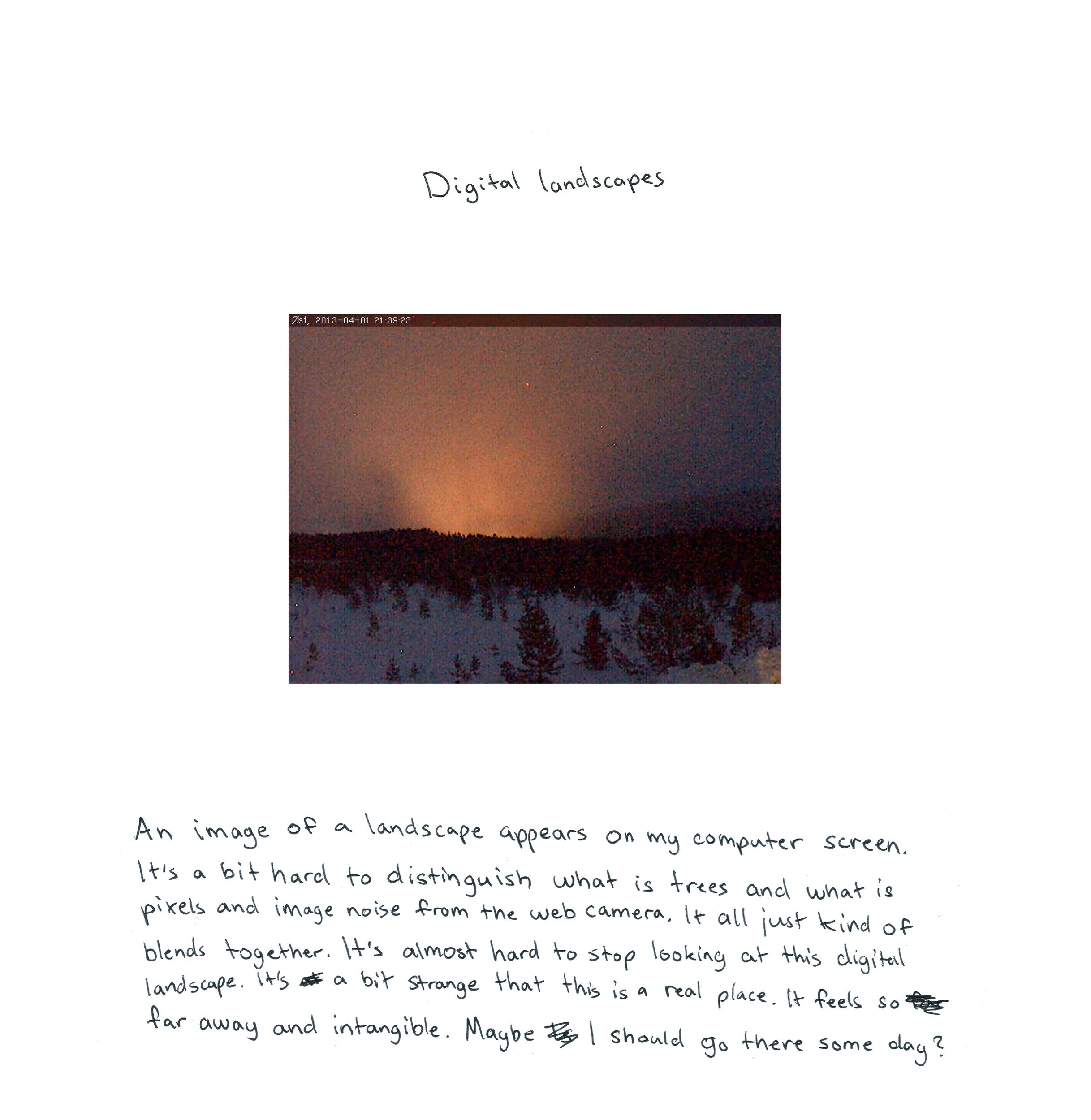

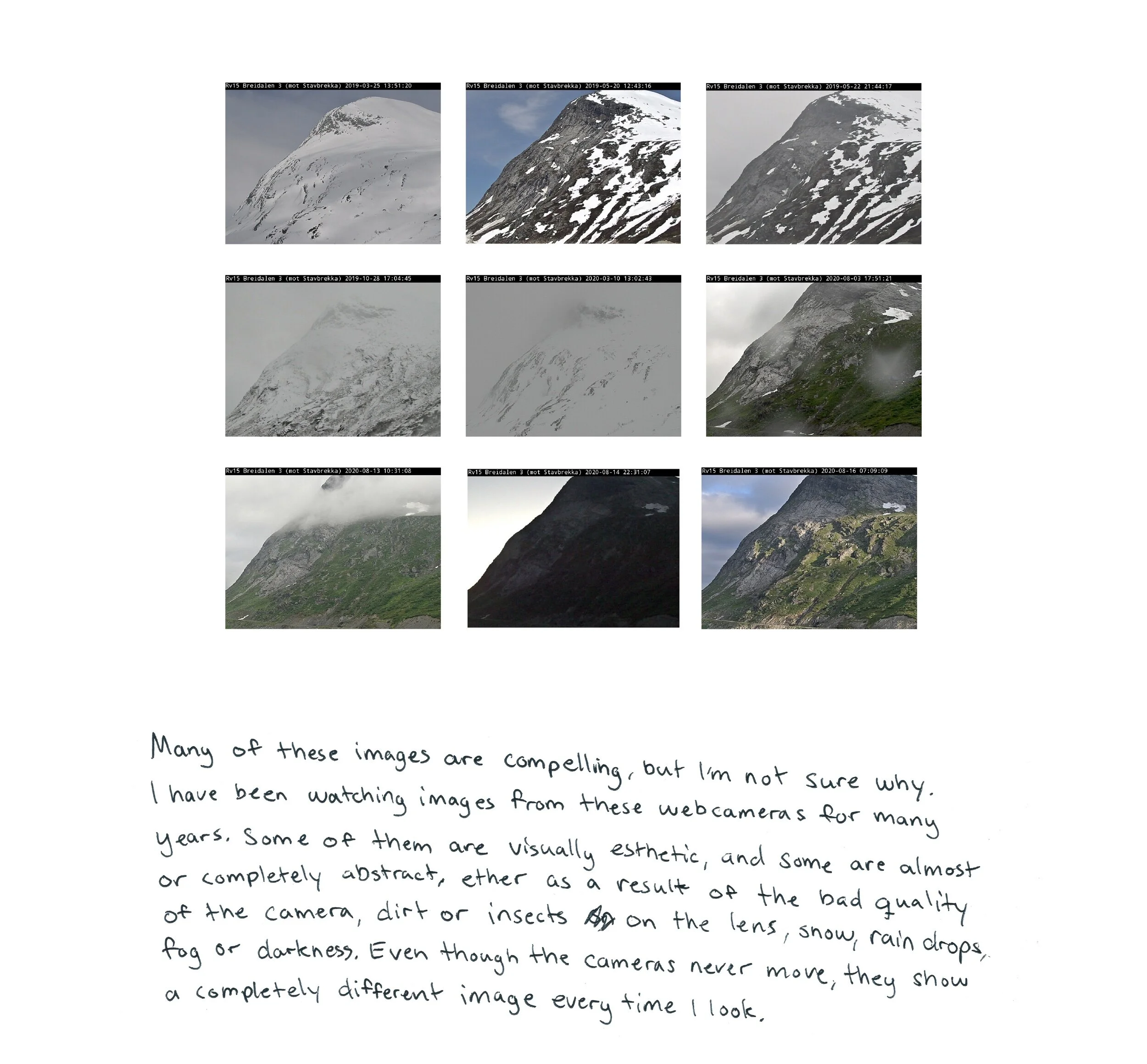

This text contains translated extracts from my master thesis written in March 2020. It is based on many years of research on photography, sight and perception. Have we lost the ability to see due to the enormous amount of visual material filling our daily lives? Are we being blinded by too much information? How can we, if need be, learn to see again? And what does seeing actually mean?

The original text was finished at the same time as large parts of the world were suddenly shut down, moved over to digital space, and thinking about touch became a pressing matter.

Le visible et l'invisible

I have walked 7,244,629 steps since I moved to Bergen 775 days ago. That is, approximately 9,348 steps per day. On a normal day, when I walk to the studio and back, I walk around 6,500 steps. Many governments now recommend an average of 10,000 steps per day. Several days this spring, my step count is down to only a few hundred steps a day.

___

There is an imbalance in our sensory system.

Vision separates us from the world, whereas the other senses unite us with it.

___

There are mirrors on the Moon to measure the distance between us and it. The mirrors were placed there during the voyages of Apollo 11, 14 and 15.

Light hits a surface, and a reflection is created. The surface's microscopic topography dictates all reflections. The surface catches the light and throws it back at us – either as the near perfect reflection in a mirror, or as the soft light on our living-room wall when the afternoon sun hits its rough surface. The smoother the microscopic topography, the more lifelike the reflection.

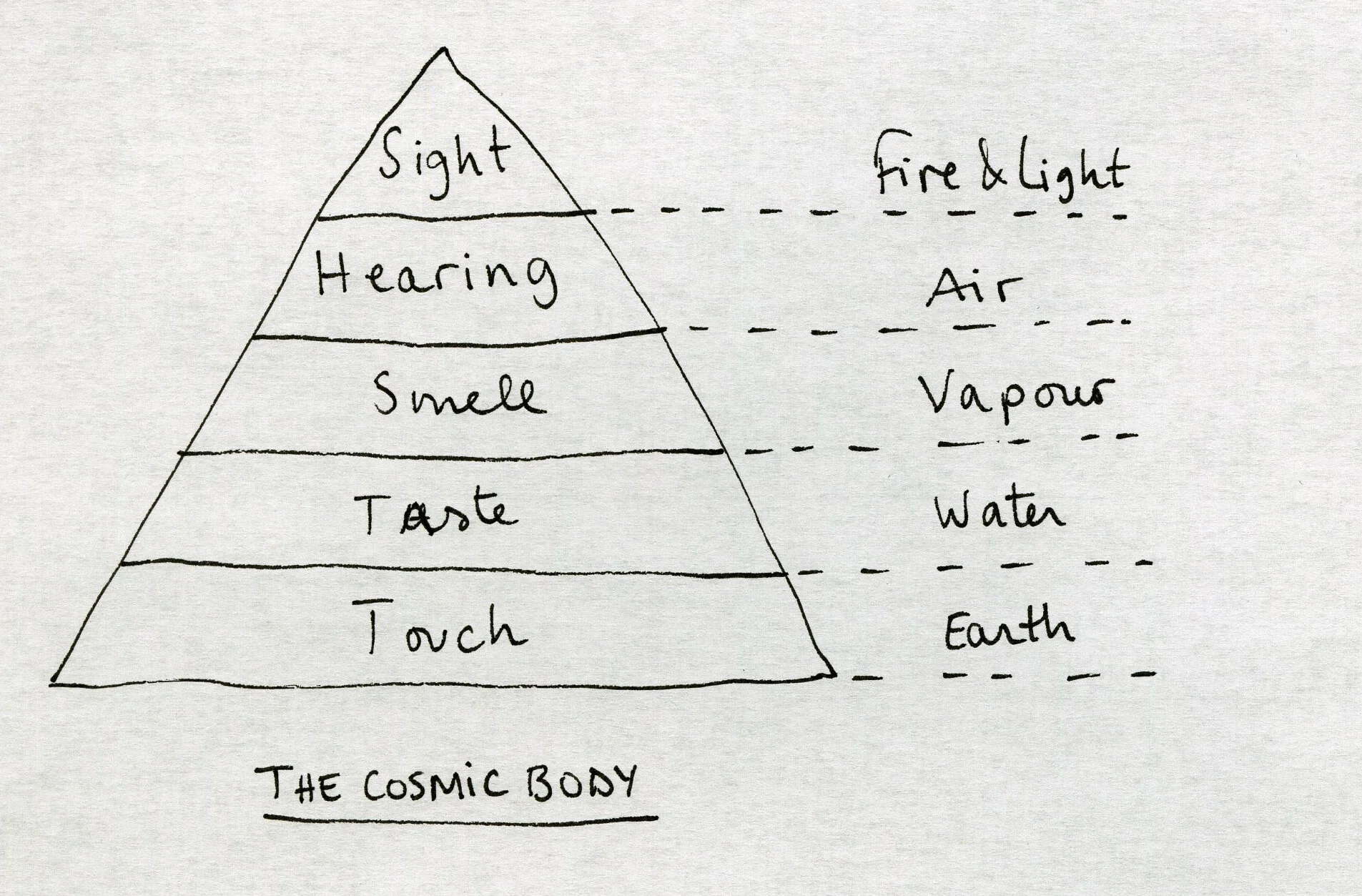

According to art historian Hans Belting, the ancient Greeks never really managed to decide if what they saw in the mirror was reality or trickery. This confusion is partly explained through their understanding of sight. Through the Emission Theory, Plato explains that we see because of light emitted from our eyes, that we see the objects in front of us only when the light from our eyes hits the object. The ancient Greeks’ idea of the Cosmic Body placed sight at the top of the sense hierarchy. Sight is light is fire is enlightenment. At the bottom is touch, and earth. Touch, treacherous, dangerous, confusing and seducing. Thus sight became the most important sense in the western world.

According to the Arab scientist Ibn Al-Haytham and his studies on optics from around 1,000 ad, there is an important difference between visibility, an optic phenomenon, and visuality, a psychological phenomenon. It is only through prefrontal mental synthesis that we are able to see, that we are able to understand and translate the light that hits our eyes. Memory and contemplation become essential in the process of seeing. Thus only details are needed to be able to understand the larger picture. We see because we have already seen.

A reflection is created when reflected upon.

Some months ago, I talked to a friend of mine who is currently working on developing eyes for robots. Their goal is to make robots that can see and recognise what is placed in front of them. A step closer to replacing humans with machines. The idea is fairly simple. The robot will get two ‘eyes’ – one working as a projector, emitting light, hitting the surfaces in front of it, the other as a camera recording and registering the shape of the object in front of it and the distance to it. They have already made great progress in their research.

___

We look, register and name. John Cage once said that we stop seeing when we start to name and categorise. ‘You look at a conifer [for instance] … and because it all looks basically alike [like other trees], you say it's a tree – and when you say that you cease to look. But only if you move from understanding to actual experience can you really begin to see.’ Seeing can lead to blindness.

___

There is something about being allowed to touch.

Last July in Japan I removed my shoes whenever I entered a space. Off with the shoes, on with slippers, or socks or barefoot. I feel an over thousand years old dark and smoothly polished wooden floor under my feet. It is burning hot in the sun, cooling, soothing in the shadows. After a long day in hard, dusty sandals, I step into the softest whitest plushest slippers and into a stark white art installation. Suddenly, I am inside the wooden floor, inside the installation. Suddenly I feel my surroundings. After a month of taking off my shoes I start to notice a certain change in perception, a certain change in the way I experience my surroundings. I have started to see with my feet. It occurs to me how much information I lose by wearing shoes. What if we wore gloves on our hands all the time?

Seeing with other senses can make us see again.

After thousands of thumbs being stuck into a hole in a column in Hagia Sofia in Istanbul and then twisted around 360 degrees for hundreds of years, the sweating-column, weeping-column, or wishing-column now has a clear scar on its side. The hole is as deep as a middle-sized thumb, and its contours are golden from the stroke of hands.

In a park in Oslo, the tightly clasped fist of a young bronze boy has become golden from the repeated touches from visitors. In the museum next door, the visually impaired could up until recently touch a few selected sculptures with signs in Braille.

At the Kiasma museum in Helsinki, all visitors are invited to press their hands against a cold, now dirty and greasy, marble plate at the entrance. Slowly we create a concave surface. Some time after my last visit to Kiasma, I read by chance in the foreword of The Eyes of the Skin by Juhani Pallasmaa, that the museum's name is a Finnish version of ‘chiasm’, a word the architect found in a chapter in Merleau-Ponty's Le Visible et l'invisible. The visible and the invisible.

There is something about being allowed to feel.

Some time before I move to Bergen I decide that I will walk wherever I go. Walking becomes my sole mode of transportation. I walk everywhere.

___

Our skin is our largest organ. Covering everything, making us feel with our whole body, the skin covers our tongue, our ears, our eyes. Touch is both external and internal. Touch is when we feel the humidity or the heat outside. Touch is when we feel pain or pleasure inside our bodies. Touch is when different body parts relate to each other without us thinking about it. Touch is the movement of our body. Touch is the only sense we cannot loose.

Lately, the word ‘haptic’ has emerged when talking about our sense of touch. The haptic refers to a combination of sight and touch, allowing us to understand and feel texture without touching. But to do this we have to touch first, to create a library of haptic memories.

Once, I experienced the lack of touch over a longer period. I had just moved away from home for the first time, and had almost no physical contact with others for half a year. It felt as if my body was imploding. Silently, slowly, sucking, sinking into itself. I was amazed and baffled. I remembered the horror stories from my childhood about orphanages where children grew up with serious disorders due to the lack of touch.

___

We break the surface. We see with our hands and feel with our eyes. They lead our fingers quickly over the touch-screens. We cannot feel our way anymore. How do you feel an app?

SOFIE AMALIE KLOUGART

Immediate Vicinity

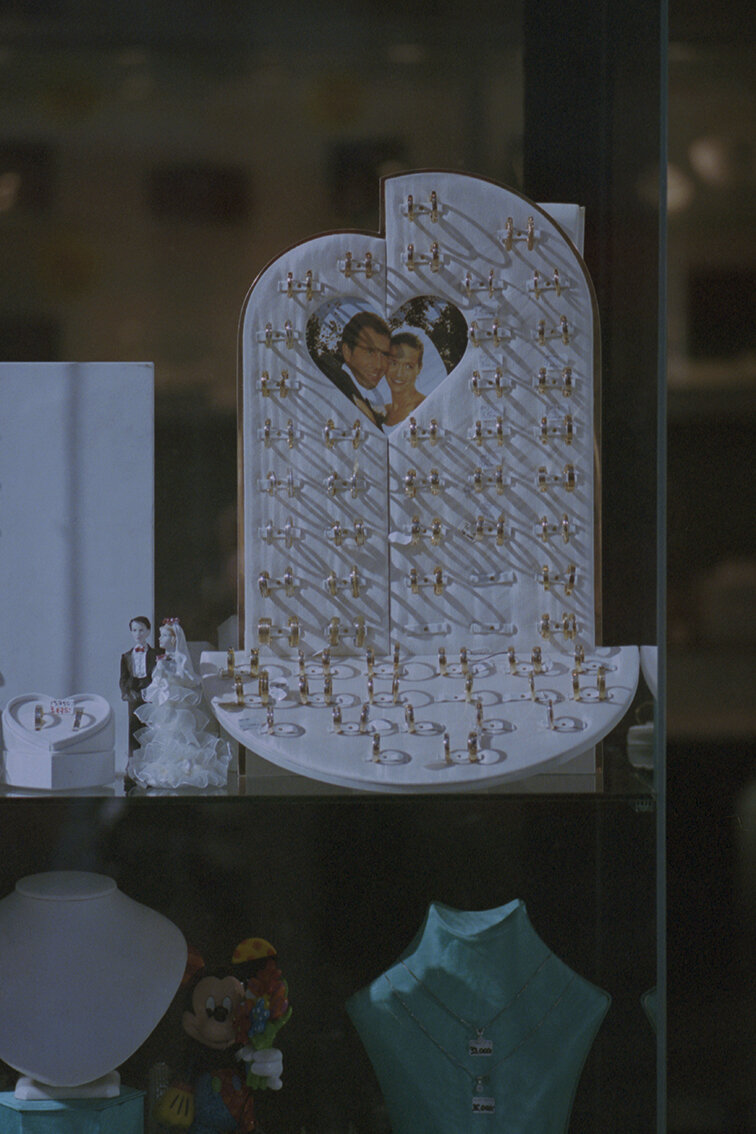

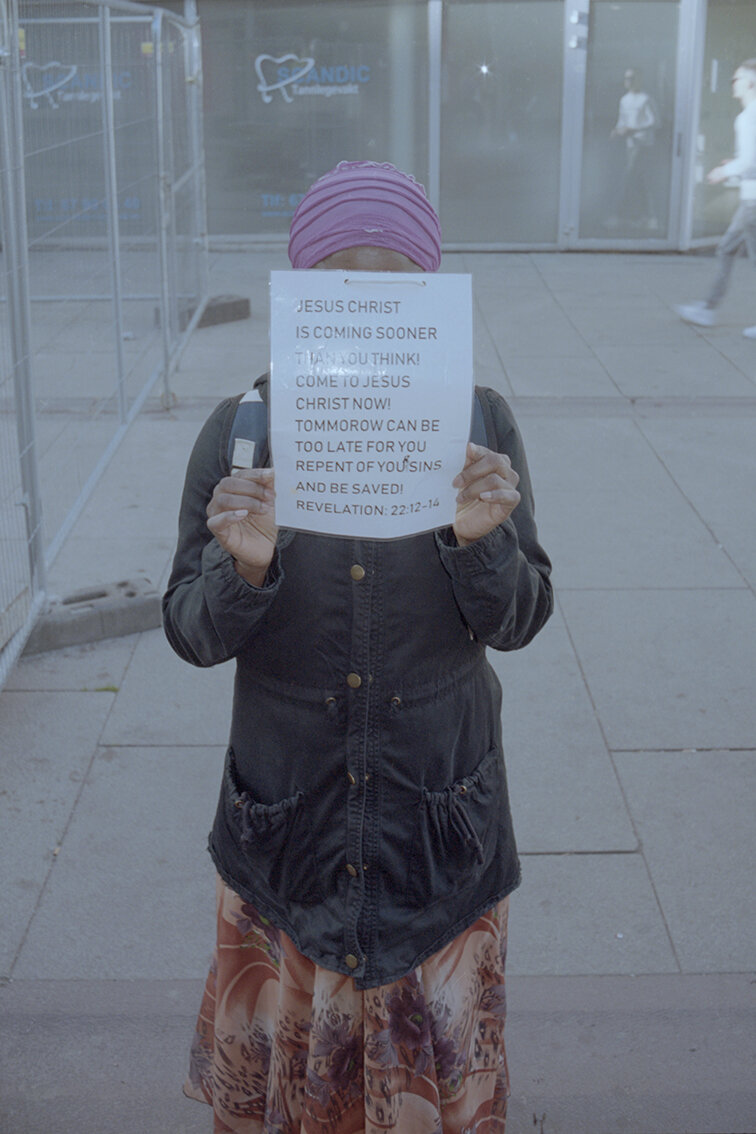

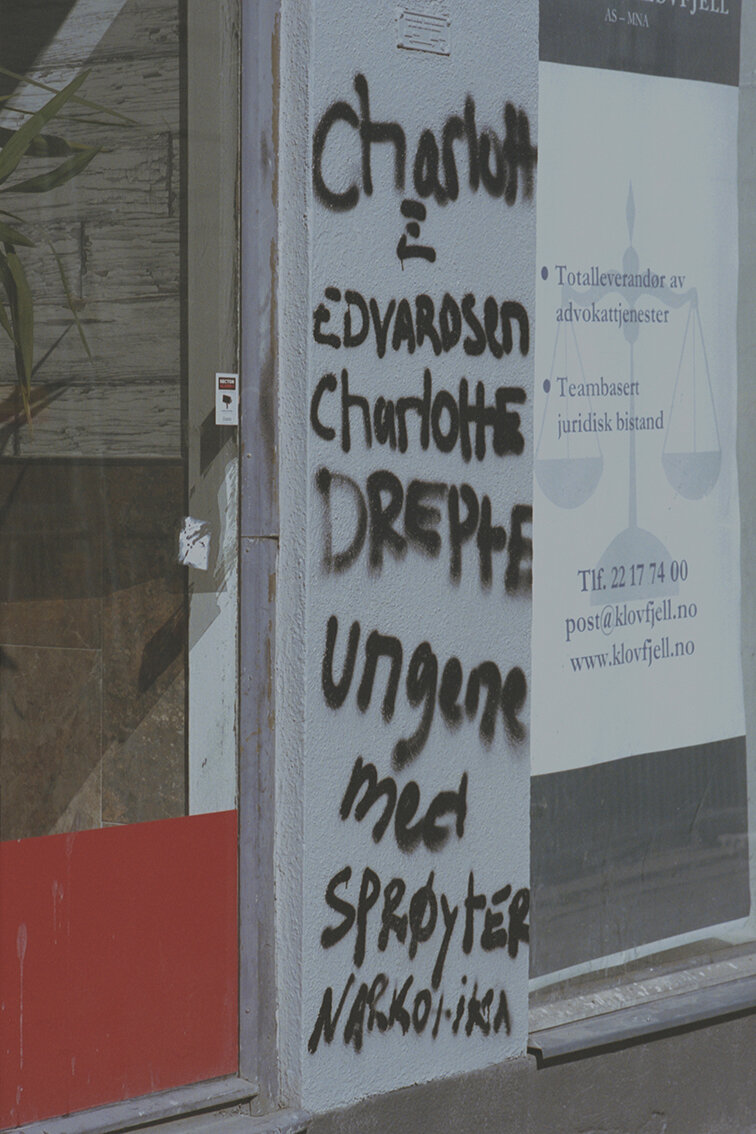

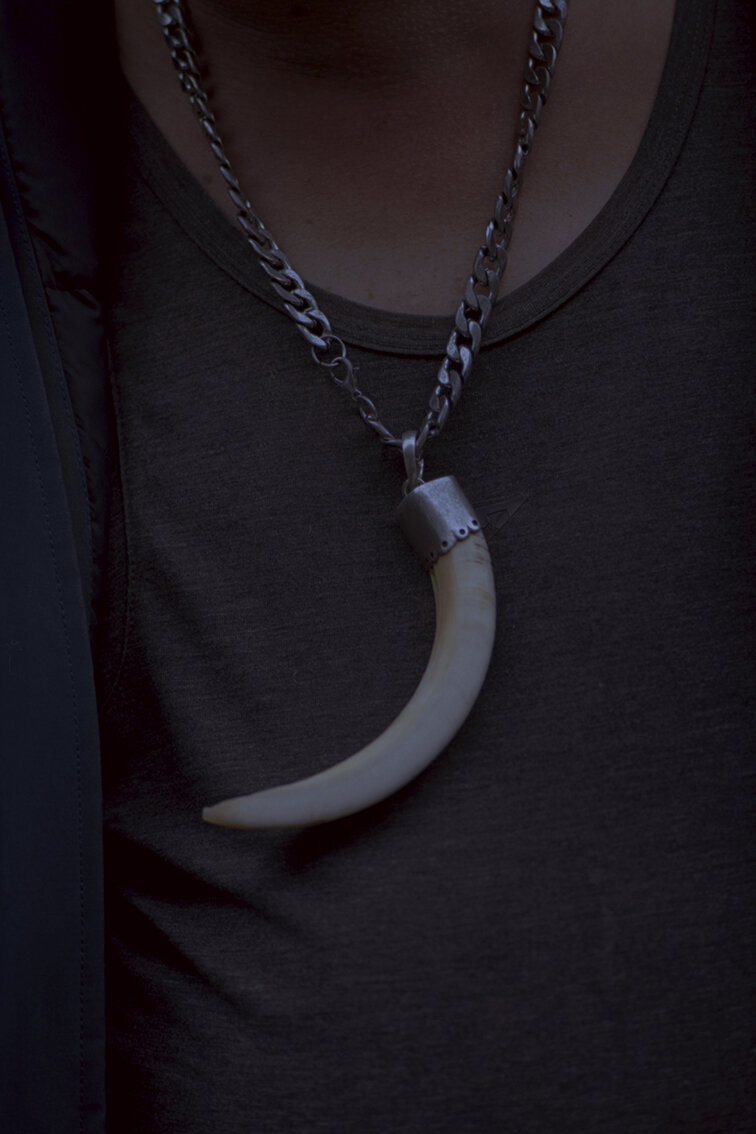

Here in Storgata, Oslo, we either have to stand close to each other or shout to be able to communicate. Storgata is being upgraded, according to the website of Oslo Municipality, and in the early hours of the day the noise from the construction work is constant. They’re building wider sidewalks, new tram tracks, more tram stops, a new water and sewer network. I don’t recognise Storgata on the architects' renderings of a future street. In the drawings, Storgata is an avenue with blossoming cherry trees and people on the move. No one is begging or injecting heroin. No large groups of misfits in front of the Gunerius shopping centre, no police, guards or social workers. Here, everything is neat and tidy.

For two years I’ve lived in Norway, and for just as long I’ve wanted to photograph the area where I live. I’m documenting my immediate vicinity and some of the people who characterise this urban space before it disappears for good.

ÅSNE ELDØY

Exercises in Structure, part 2.

Concrete fragment A, satellite series, I-III (2020). Concrete fragment B, inside series, I-III (2020). Quarry no. 06, no. 23 & no. 24. (2019).

Time is now longer than other times. It moves slower than it used to. It’s a time for practice. Recurrence. Repetition.

ANTHEA BEHM

I started making photographs when I was in high school through an after school darkroom class. It was a volatile time in my life, and the darkroom provided a space of refuge.

My high school darkroom, like many community darkrooms, had a series of enlargers in a row that were separated by dividers. Working in the dark at one of these stations gave me much needed space where I could pause and take cover. As in many such darkrooms, the trays of chemicals where you process your prints were shared. When it was time to put my paper through the chemistry, I moved from a singular, solitary position into a communal one. This was a space of gathering, and also of care: when moving your prints through the trays, you needed to be aware of affecting other prints that were also mid-process.

This separation of space was not absolute. Even when you’re alone at your enlarging station, you must be mindful of your community. For example, you must ensure that you don’t turn on your enlarger with the negative carrier open, which could mistakenly expose your neighbor’s paper to light. And even though—like much human activity—analogue photography can be destructive to the environment, the rules of the darkroom help minimize harm; for example, never pouring fixer down the sink.

Today, I am processing prints in my studio darkroom in Gainesville, Florida, where I am also sheltering in place. I work alone, but within this distancing there is also connection and care. Our experiences and our relationships—to ourselves, each other, and the world—are not fixed in a final photograph. They are the entire process.