JEET SENGUPTA

As the situation around the world gets worse every day with the news of the rise in deaths, I’ve become paranoid about losing my parents. Even though we’re living together, I cannot get this fear out of my head. A number of times, I’ve imagined that they are dead.

In the early stages of lockdown, I used to check my parents’ temperatures every other day. The seriousness of the disease and its ability to spread within the community has made me doubtful of the people on the streets, even neighbours and friends. Every morning, half awake, I call out to my mother from my room to get her response, to know she’s still there. When I hear her voice, I go back to sleep again. Somehow this makes me feel safe, even in my dreams. But I’m scared that one day, I’ll hear only silence.

It’s been over two months now. The fear of the pandemic has now also become fear of people. I am worried that I will isolate myself from the world even after the lockdown ends.

DAVID GEORGE

16th APRIL 2020.

AS A LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHER MY PRACTICE HAS BEEN COMPLETELY CURTAILED BY LOCKDOWN SO I HAVE TAKEN TO RECORDING MY DAILY 5AM DOG WALKS AROUND HACKNEY, LONDON ON AN OLD IPHONE 5 .

SARAH MEADOWS

I'm thinking about spring, all of the spring happening that I can't experience. Fertility, growth, and life cycles are cycling onward outside of my house and I wish I could be out there.

Frog and salamander egg images from google searching in my room. May 13, 2020.

THORA DOLVEN BALKE

I look forward to the time I can step outside this moment and find a language to describe it from a distance, right now it just swallows me whole.

CAMILLA REYMAN

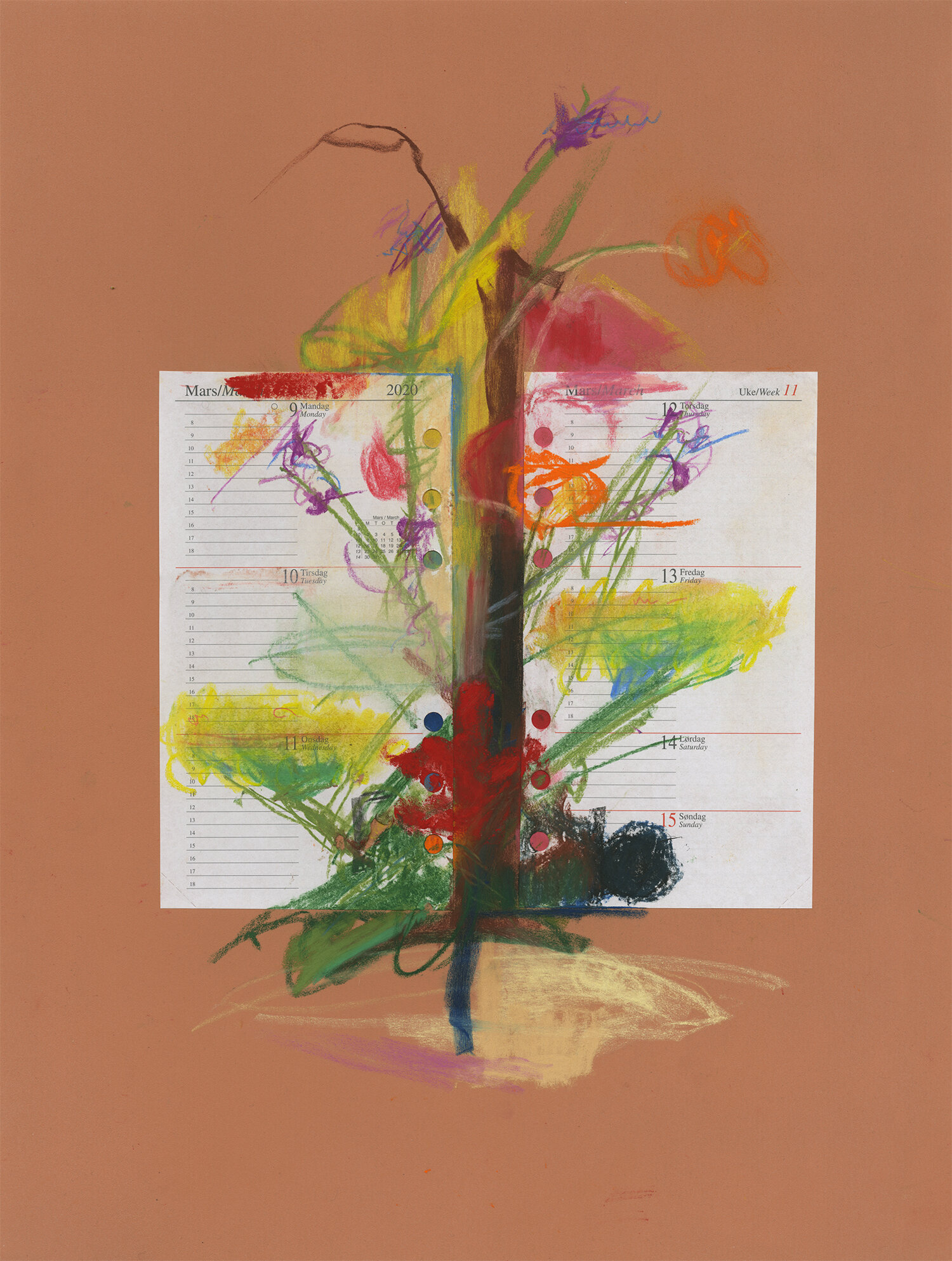

Camilla Reyman, What day is it?, 2020.

I have been debating with my self for years wether my obsession with the square was ok, and in these times of confinement I finally feel it is an appropriate subject/object to engage in ◼️◼️◼️.

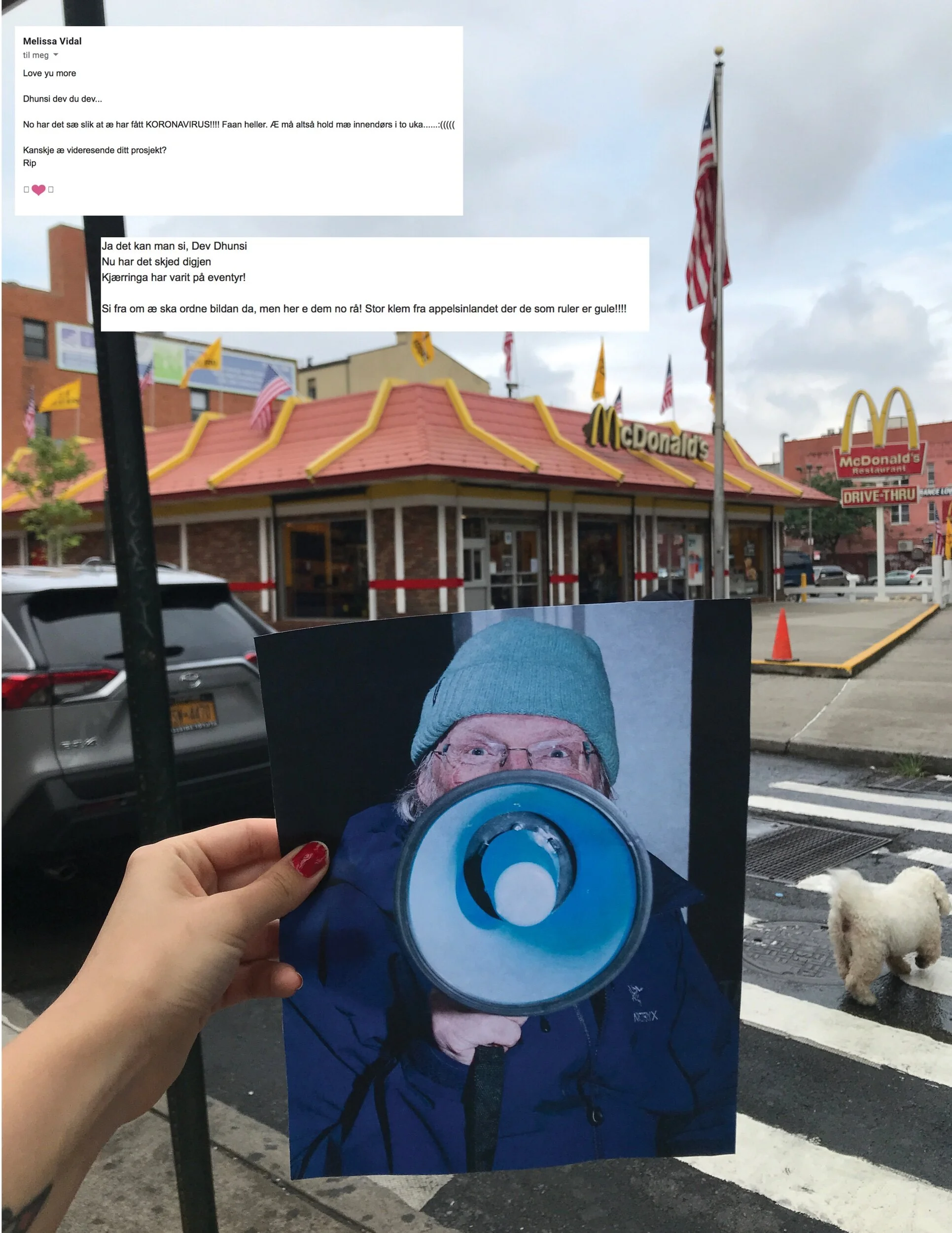

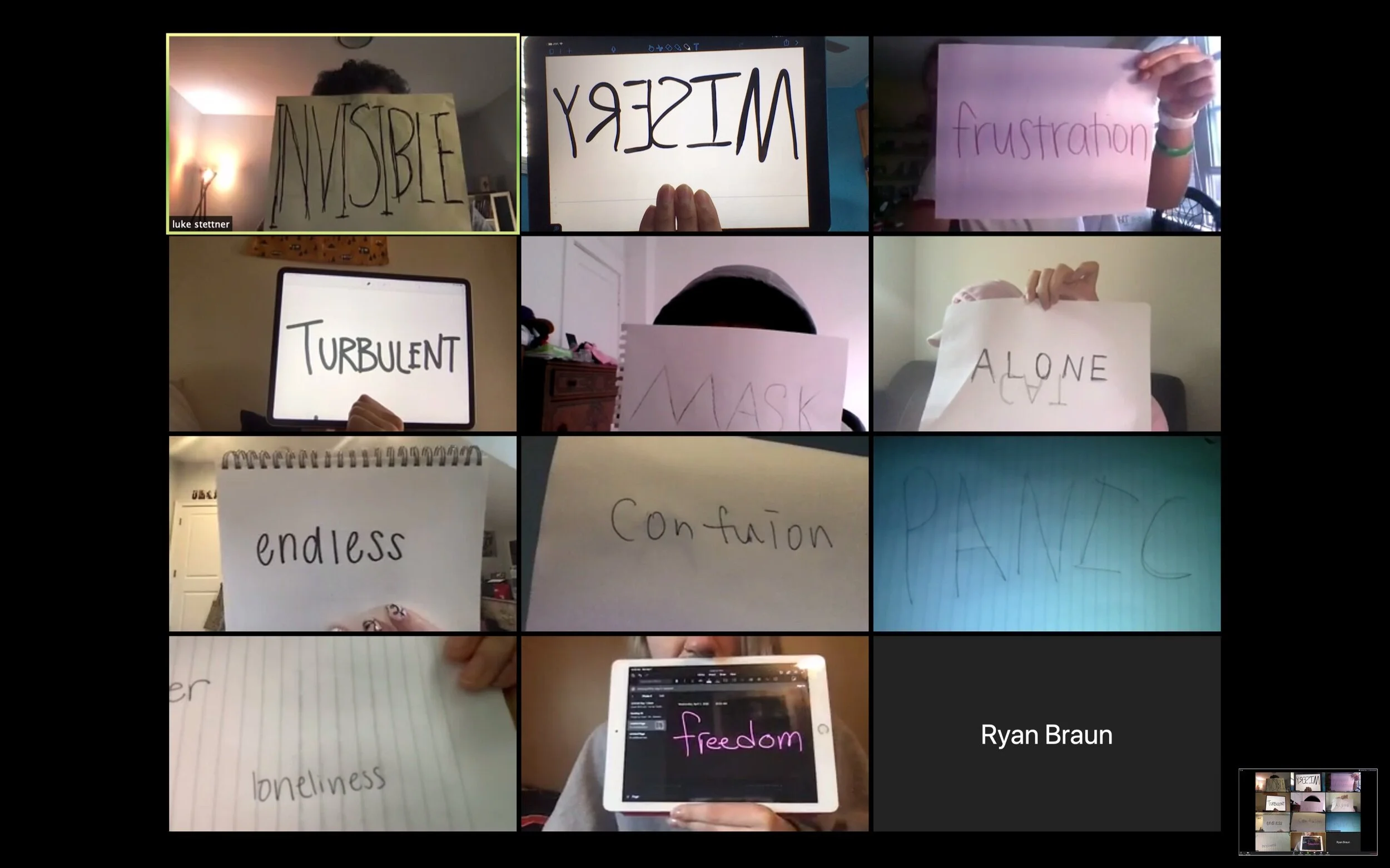

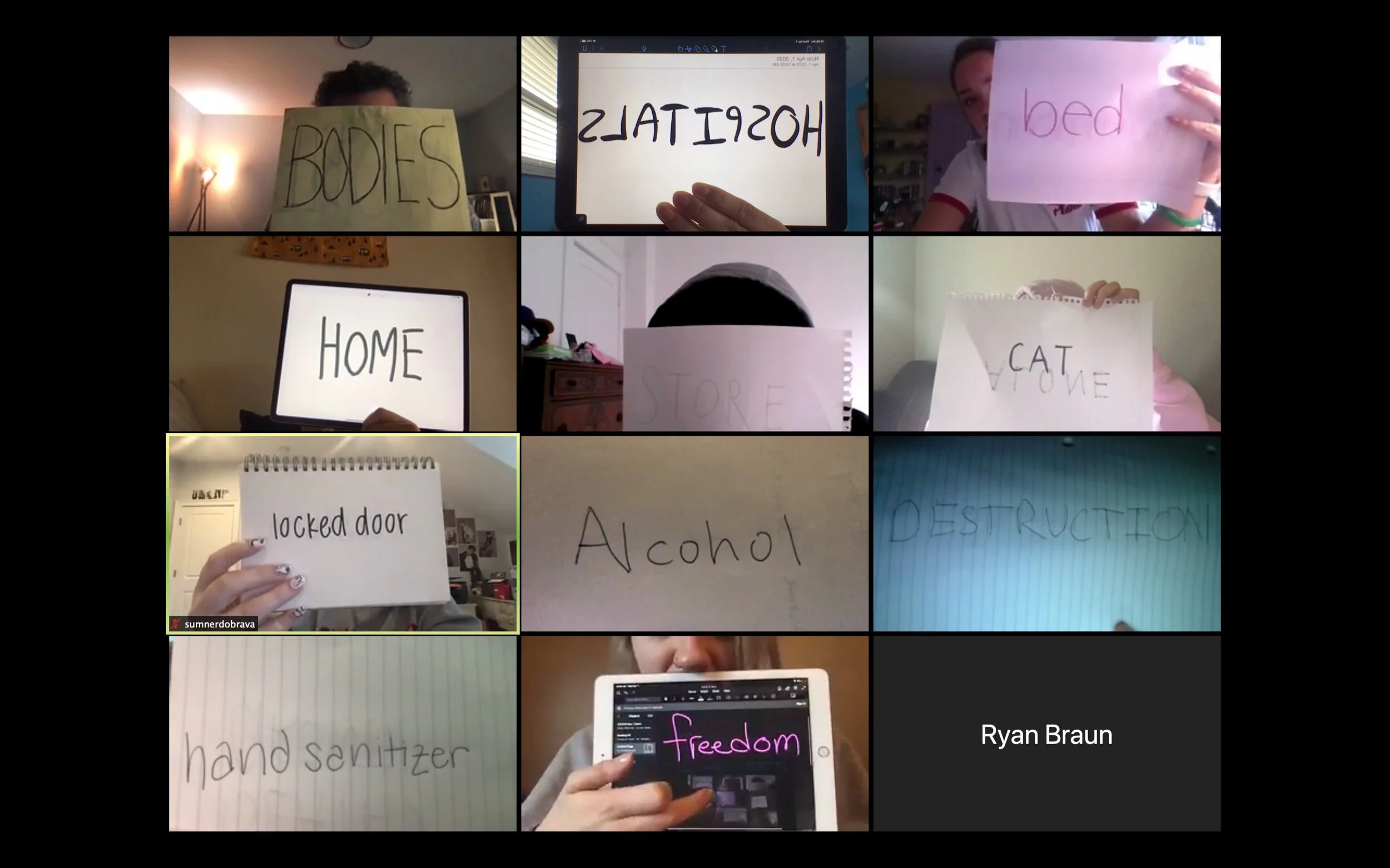

LUKE STETTNER

Luke Stettner collaborated with his darkroom photography students from Ohio State University during a zoom class session. Together and at once across their screens, they held up concrete and abstract nouns in response to the time we are living through. Grace Advent, Enrique Arayata, Ryan Braun, Margaret Derrig, Sumner Dobrava, Sarah Estes, Ella Feng, Jeramey Frelin, Jet Ni, Luke Stettner, Connor Yoho, Zhuoran Zhang.

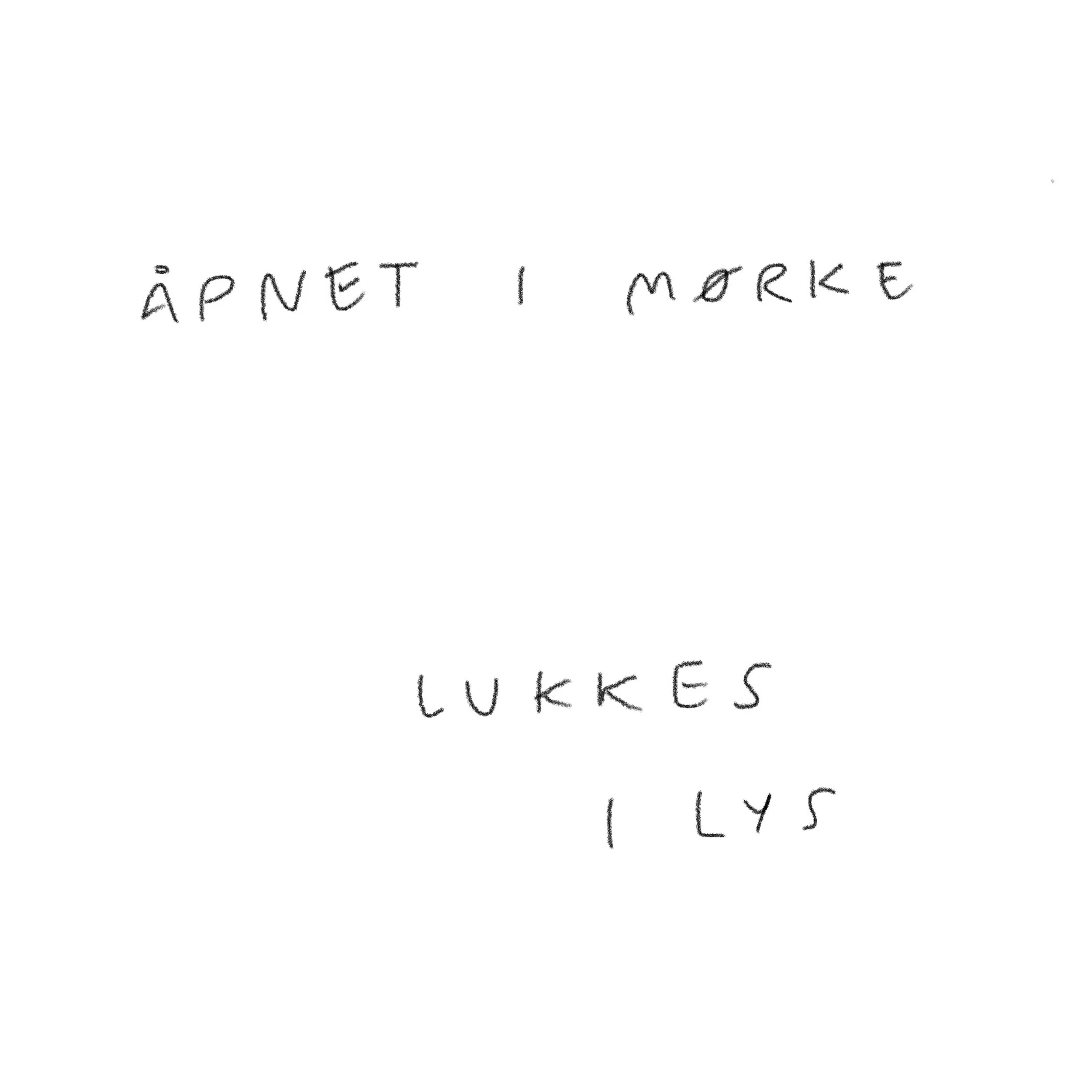

SOLVEIG LØNSETH

Visual Wanderings

Objektiv has initiated a new series of works, Visual Wanderings, made especially for our online journal. We are inviting photographers from all over the world to create art that responds to our new situation: what does the lock-down mean for their work, what is important for them to convey, and what are their reflections on the time to come?

Contributions can take any form, from a photograph to words, a series of pictures or a meme. Each photographer will then be asked to pick another artist to create a work. The works don’t have be related to each other, but we want them to reflect how the virus informs their work and life. In this way, we will create a visual dialogue that runs across many different countries, in order to get a bigger picture of how this crisis and its aftermath are playing out for artists all over the world.

To present these visual wanderings, here is a photographic text by Solveig Lønset. (Opened in the Dark, Close in Light.) Take care.

VIBEKE TANDBERG

Vibeke Tandberg, Old Man Going Up and Down a Staircase, 2003.

Afterimage by Jocelyn Allen:

I’m currently pregnant, and I’ve never been before, so it’s a big change for me and my body. I have photographed myself for over 10 years and at the moment I am working on a series about my pregnancy. As a result, I have been looking to see how other women have photographed themselves during this time, as well as post-birth, and early motherhood.

A series that sticks out in my mind is Vibeke Tandberg’s Old Man Going Up and Down a Staircase (2003). In the work she is pregnant and dressed as an old man with a mask on. I imagine she did this to playfully talk about the restrictions and difficulties that pregnancy can present. Tasks that were once simple like walking up and down the stairs become more difficult, but with pregnancy it is often only a temporary change. I like this series as it is quite different to other work that I have seen. It is playful whilst commenting about something very relatable that might ring true to you even if you have never been pregnant, but experienced something else like having a broken bone or feeling rough after a night out.

Tandberg’s work makes me think about my grandmother when I visit her house. She wants to do things for me as I am pregnant, but it is difficult for her because of the changes to her body now that she is older. She says she will make me breakfast, but instead I make her breakfast as I know it is much easier for me to do it. She gets frustrated whilst going shopping and everyone opens doors for her as it makes her feel like she looks old, whilst I get irritated by people meaning well but telling me to eat and rest well, like I have forgotten the basic needs of being human.

I am currently about halfway in my pregnancy and my movements are becoming more restricted. Picking something up off the floor requires some repositioning and my days of putting my socks on whilst balanced on one foot will soon be paused (this morning I did one, but gave in and sat on the bed for the other one). I know that even though my body will probably never be the same again, I will be able to do these simple things again. Whereas for my grandmother these changes are now permanent and her ability to do these things will only get worse.

ERIN SHIRREFF

Afterimage by Erin Shireff:

I was working at a desk sometime in the mid 2000s, back in Brooklyn after graduate school, endlessly scrolling through Gawker.com as I tried to avoid thinking about the vague direction of my life when this image rolled onto my desktop screen, no accompanying text, carrying the header “Ghost in the Machine.”

It was a typical Gawker post — New York-centric, slightly caustic — and it hit me in the way it was likely intended. I probably laughed. But the picture itself, a low-fi cell phone snap taken quickly (maybe on a Blackberry?), it stayed with me and provoked something less formed, more ambient in my mind.

After a beat you get that this isn’t documentation of a performance, the person in the photo isn’t pulling a prank. It’s likely a picture of one of the many, many people living in New York who don’t have a home, who use the subway as a place to sleep or rest. Someone trying to get just a bit of privacy within a life that probably affords them very little. So it felt wrong, or problematic, to think of this being a “relatable gesture” but I did. And I do. Abstract the conditions of this life I can’t imagine through a degraded photo on a website and I remember how when I first moved to the city from the desert I felt physically damaged, daily, by the number of faces — eyes — I had to see each day. Most days I felt enormously, thrillingly anonymous but that feeling could tip when the wave of humanity became a sea of individual people. Eventually I acclimated or maybe I just numbed out. Maybe I was already part way there when I looked at this picture and laughed.

It makes me think, too, about how I fetishize privacy. I am alone in my studio most of the day and I’m not convinced it’s a super healthy way to live but it’s a condition I rely on in order to hear myself clearly. That’s old fashioned I guess? The idea of privacy or aloneness being required for thought? Or maybe the notion of privacy itself — keeping something entirely to yourself, that being enough, not telling anyone — is just over. Sometimes I think we care about privacy only when we’re asked if we do, or when we think it’s being taken away.

Gawker is dead now, Blackberries are done. The sensibility of the writer that would have made that post has probably shifted. My own self-indulgent post-grad anxieties about creative autonomy that probably drove my connection to the picture in the first place — they’ve thankfully faded. Back then I printed it out on my desktop Epson and it’s here on the wall in my studio now like it was in Brooklyn for so many years. I’m gone, too. I travel on a different subway in a smaller city where it feels much harder to disappear. The ghost hangs above my sink in a black metal frame I picked up at Michael’s, discolored by shitty inkjet banding and years of UV damage. I guess now it’s a souvenir? I wouldn’t say it haunts me, but it’s never quit working on me, never not made me uneasy.

YORGOS LANTHIMOS

A still from Dogtooth by Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009.

Afterimage by Camille Lévêque:

I’ve always been strongly influenced by cinema. I’m rarely interested in photography, but often in videos made by artists. Film stills remain on my mind in a way that’s slightly different from photographs.

Since the first time I watched it in March or April, I've kept a screenshot on my phone from the film Dogtooth (2009) by Yorgos Lanthimos, who represents the new wave in Greek cinema. He also made The Lobster (2015) and The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). His films are very visual, and he has what I would call the eye of a photographer. They’re also extremely dark, and Dogtooth leaves you feeling anguished, but it hides its darkness behind a lighter appearance and colourful scenes. The movie as a whole is beautiful, but each individual scene is well orchestrated: if you paused at any moment, you’d have a really interesting still image.

Dogtooth is about an isolated family. The parents keep their kids completely outside the world by creating a fantasy to keep them at home. I have one scene in particular on my mind – the one that I saved on my phone. It depicts a birthday. We don't know whose birthday it is, but of course, only the family is present. At one point, the daughters perform a dance to their brother’s guitar, and it’s terrifyingly awkward. The scene arrives near the end of the film, and a lot of tension has been building. It reaches a point of almost unbearable uneasiness and you know something terrible is bound to happen, and yet it only becomes increasingly absurd.

I’ve grown up with an education in cinema and watched all the classics, so many films made these days don't interest me at all. I’m interested in an experience rather than entertainment. My expectations when it comes to cinema are ridiculously high. When I see a movie, I want it to change my way of thinking, and almost change my life, and Dogtooth does this, in a way. I regularly look at that scene on my phone. I really love the grotesqueness, absurdity and darkness in the film. But it’s hard to watch – almost like witnessing an accident and being unable to look away.

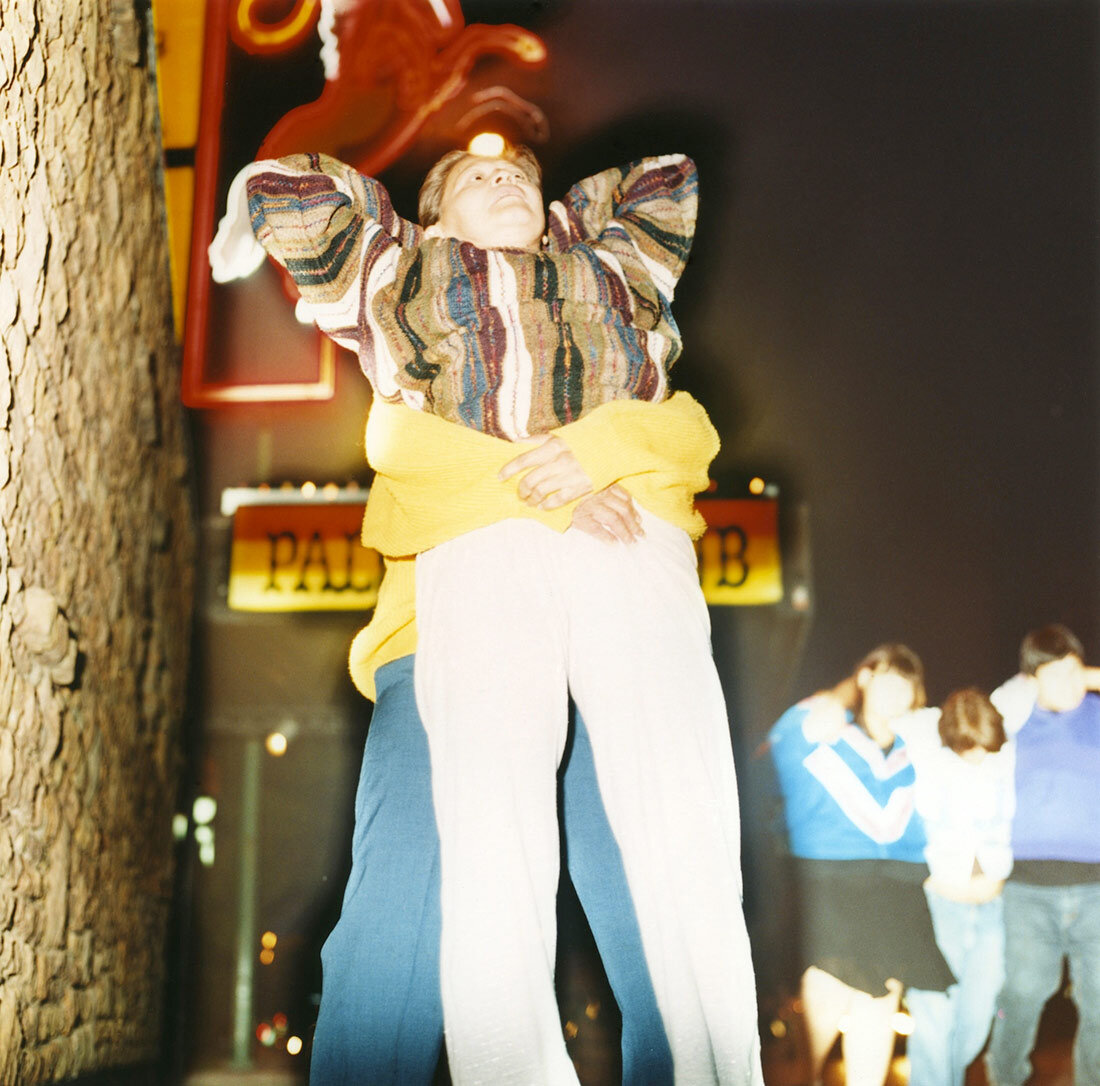

ELAINE STOCKI

Elaine Stocki, Palomino

Afterimage by Curran Hatleberg:

Even though it’s been years since I first saw her work, many of Elaine Stocki’s photographs have stuck with me and claimed importance in my mind. This is probably because they evoke such a unique intensity of mood and feeling. They are haunting, and they just don’t look like any other photographs I see. Palomino is no exception. It is a wild, swirling chaos of color and gesture that gives off a burning heat. It almost scares me. Somehow Stocki figured out how to summon the dream state, or enter into a hallucination where the normal rules of reality don’t apply. I have no idea how she does it. One of the many joys of this picture for me is surrendering to its mystifying trance, letting its force pull you in.

Another part of the magic of Palomino – aside from the distinctive mood and feeling – is that it rejects easy interpretation. It’s impossible to pin down. It suggests clues as to what might be happening but reveals nothing. Even after studying the photograph for a long time there are no definitive answers. It’s a moment that is powerful precisely because of its lack of clarity. To me, it’s this open-ended quality that makes this image so amazing. Stocki invites the viewer to participate in their own creative interpretation and invention, allowing them to trust their imagination and let go. Palomino, like all my favorite artworks, is experienced more than understood.

A while back I read something the poet Mark Strand said in an interview that I saved in my phone. I keep returning to it now and then. Looking at Palomino, it seems appropriate here: “…we live with mystery, but we don’t like the feeling. I think we should get used to it. We feel we have to know what things mean, to be on top of this and that. I don’t think it’s human, you know, to be that competent at life.”

PATRICK KEILLER

Patrick Keiller, a still from LONDON, 1hr 40 min, 1994.

Afterimage by Helene Sommer:

I stumbled across the work of Patrick Keiller over 10 years ago, as I was scavenging the web for one thing or another. It was a clip from Keiller’s film London from 1994 and it immediately resonated with me on numerous levels. The first image is a shot of the iconic Tower Bridge in London. It’s a dreary and grey image. Quite unspectacular for a motif usually belonging to postcards and mugs. In general most shots in this film are seemingly both mundane and laconic, depicting ‘ordinary’ though very precise observations from everyday life in a city. There is no camera movement, only a static camera. No actors, no scenography. The bridge opens and a cruise ship slowly sails through.

In stark contrast to the imagery is the voice-over and soundtrack. The nameless narrator, who arrived on the cruise ship where he worked as a photographer, is meeting up with his ex-lover Robinson after 7 years. We never see either. The film is a wonderful mix of fiction and documentary. The soundtrack, in addition to the voice-over, has multiple references to the dramaturgical use of film music that contrasts the imagery. The narrative is complex and sometimes surreal in its multiple idiosyncratic references and juxtapositions - simultaneously very funny and deeply serious.

Together with the nameless narrator, the eccentric and visionary Robinson sets out to understand the ‘problem’ of London through a melancholic survey of the ruins of an urban ideal. A kind of psychogeographical travelogue investigating the multiple layers and textures of the city. Robinson solemnly drifts around London and reflects upon the historical undercurrents of the city’s many streets and buildings. He traces views that once inspired great painters, ponders Baudelaire while drifting through a Tesco supermarket, notes that in Lambeth there is a fence made out of beds from air-raid shelters, plans for a contemporary postcard series with the city’s homeless, tracks down flats of famous poets and traces the aftermath of an IRA bombing and the economic crisis in a post-Thatcher landscape.

Since watching London for the first time, I have seen most of what Patrick Keiller has produced; films, books and exhibitions. And I keep coming back for more. It’s the type of rare relationship that never gets old. London (1994) is the first part of a trilogy which includes Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010), all highly recommended.

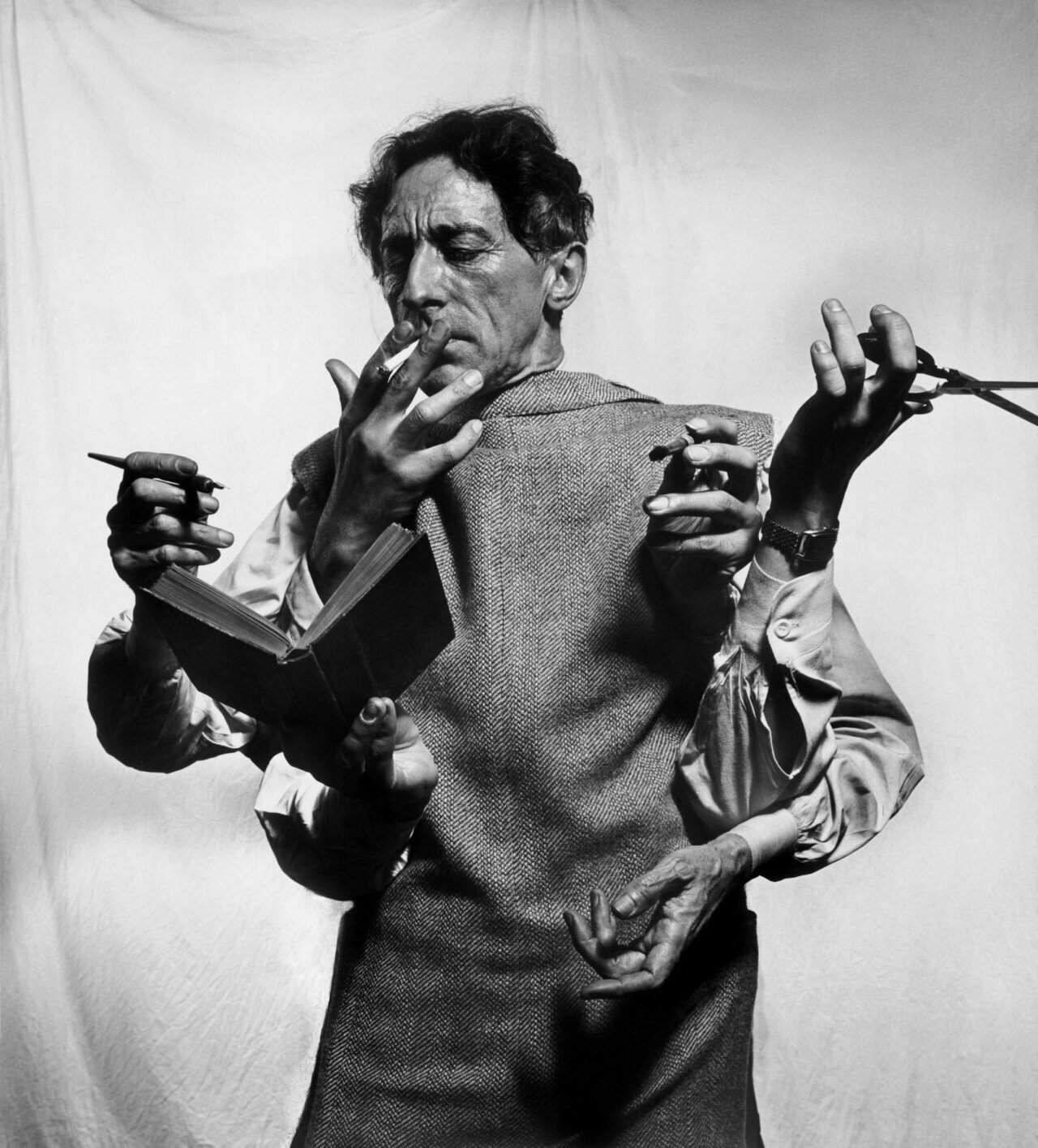

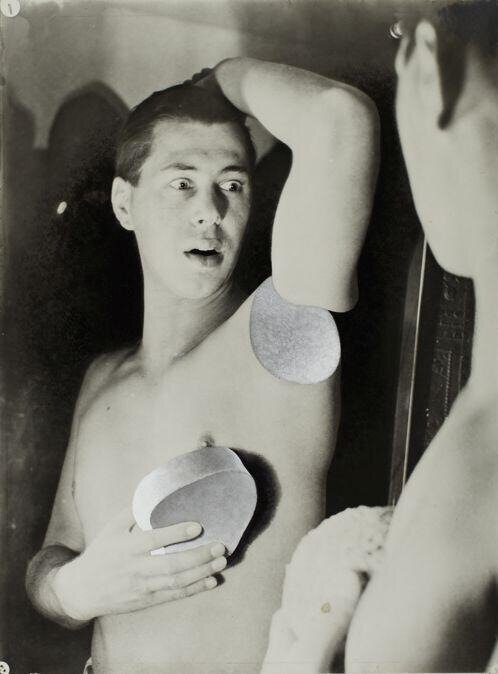

PHILIPPE HALSMAN

Philippe Halsman, French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. NYC, USA. 1949. © DACS / Comité Cocteau, Paris 2018. © Philippe Halsman | Magnum Photos

Afterimage by Alix Marie:

Perhaps because it was summer when I was asked by Objektiv to write about an image my choice has been influenced by the past. I was in France and had spent a lot of time sorting through hundreds of family photographs; postc Marieards and memorabilia from various periods of my life. The two images that came to mind were Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) from 1932 and Philippe Halsman’s photo of the French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau from 1949. Bayer’s self portrait is an image I discovered as a teenager at the Bauhaus Museum on a school trip to Berlin. It has been in each of my bedrooms, in the form of a postcard or poster ever since. But then I felt that talking about it might actually kill the mystery of its power over me, so I’ll talk about Cocteau.

Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait), 1932.

Halsman’s portrait returned to me as he has always been one of my heroes. Still today, as I am preparing my next show at Musée Des Beaux Arts Le Locle, I find images from La Belle et la Bête popping up in my head constantly. My family comes from cinema, and films are more influential in my practice than anything else, perhaps even more specifically the favourite ones from my childhood. Cinema is historically and socially a big part of French culture, Paris being the only city in the world where you have one cinema screen per hundred inhabitants. The average of going to the cinema is twice a month, it is very much part of our habits, and it’s something I miss here in the UK.

I remember as a child looking for through an encyclopaedia on cinema and for Cocteau they just wrote: génie à multiples facettes. I thought that was the most wonderful definition of an artist. This is exactly what the portrait depicts: Cocteau’s ability to write (poetry, plays, screenplays), set design, draw, paint and direct films. In a sense I think we can also read this portrait of an artist in a contemporary sense, as artists we are asked to have an incredible amounts of skills in order to survive: make good work, know how to write about it, know how to speak about it publicly, do your own PR through social media, know how to sell your work, teach...

Thinking of my practice which often mixes mythology and autobiography, and my passion for mythological antique sculptures, I think perhaps it originally came from Cocteau. As when he turns Lee Miller into an armless goddess in Blood Of A Poet for example. The transformation, if I remember correctly, was achieved by covering her in flour and plaster which must have been extremely uncomfortable. It is another aspect of Cocteau’s films which fascinates me: his DIY special effects which in themselves carry so much poetry. I think for example of when Jean Marais walks through the mirror in Orpheus for example, it is just cut and paste, instead of a mirror it is water when he goes through. This is something I try and keep in my practice; it comes from the everyday and the ordinary as I try to make and fabricate everything I can myself and often repurpose domestic objects. The manipulations in my work are physical, I never manipulate an image digitally. In the end these two images share a lot in common, they use analogue tricks to achieve a poetic and political portrait or self portrait of the artist, and they carry a reference to antique sculpture, all aspects which have fed my practice since very early on.

ROBERT FRANK

Robert Frank. Words, Mabou, 1977. Vintage gelatin-silver print. 31,2 x 46,8 cm. Collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Gift from the artist.

Afterimage by David Campany:

When people look at my pictures, I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read the line of a poem twice.

In 1954-56, Robert Frank was on the road in the USA, making the photographs for what would become The Americans, perhaps the single most influential book by a photographer. Swiss by birth, Frank came to America in 1947. Politicians and the mainstream media were full of post-war optimism fueled by consumerism, television and Hollywood. All Frank could see was disappointment, alienation, and systemic racism. Published first in France in 1958, the images were accompanied by an anthology of quotes from various writers about the country. When the book appeared in America the following year, the quotes had been replaced by a foreword by Frank’s friend Jack Kerouac. The publisher was Grove Press, the primary outlet for the Beat generation poets.

Frank’s images were willfully subjective. They were also highly sophisticated redefinitions of the nation’s iconography. The stars and stripes flag recurs, but it is tattered or obliterating the faces of citizens. Movie stars look uneasy. Manual workers feel dejected. Passengers on a trolleybus arrange themselves by race. Motels and gas stations are bleak and forgotten. But through the metaphor and allegory there was also a romantic and angry longing for something better.

Modern America is a restart, an experiment. Its keenest observers in photography, film, painting, literature, theatre, and poetry have been monitors of that experiment. The Americans divided opinion but its reputation, particularly among other photographers, grew rapidly. For some, Frank had opened a rich new vein of image making. For others, his achievement could not be surpassed and new directions would have to be taken. Frank himself left photography almost immediately after The Americans, and took up filmmaking. In 1971, he moved from New York to Mabou, in remote Nova Scotia, Canada. He returned to still photography but not in pursuit of singular, iconic images. He made collages, mixing photographs and writing in different ways. As he pushed onwards, he looked back from time to time. The Americanswas becoming something of a counter-cultural monument. Museums and collectors were beginning to acquire prints. Frank grew reluctant to talk about The Americans, feeling that all he wanted to say had been said, and was in the pictures anyway. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the book has become the most discussed and analyzed of all photographic projects, the subject of endless essays and assessments.

In this photograph we see prints hanging on a washing line, on the coast of Mabou. There is an image of people on a boat. Frank shot it on the SS Mauretania, the day before he arrived in the USA. There is a photograph taken at a political rally in Chicago, 1956. It is one of the best-known images from The Americans. On the right, the word ‘Words’. Perhaps it was Frank’s sign of exhaustion with the endless talk about his work. Perhaps it was a substitute for an image, a placeholder for a language to come. Words have accompanied and haunted photographs from the beginning, and ours is a thoroughly a scripto-visual culture. Images conjure up words, and words conjure up images. Both are substitutes for realities they can never quite express, even with each other’s help. They are apart yet connected, like transatlantic friends.

The text is from Campany’s forthcoming book ‘On Photographs’, Thames & Hudson, with a few changes for our series.

LEA STUEDAHL

Afterimage by Lea Stuedahl:

A while back, my grandfather gave me all his negatives, pictures he had taken from when he was a teenager until he became a father. Through at these images I got to know him as more than my grandfather - whom I already love and admire. I got to know parts of him that has always been there, the core of his personality. In some ways it makes me understand him in a way that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. This is something I find compelling with photography; the way we might try to understand the photographer at the same time as we try to understand the photograph. There is so much identity attached to it. What we photograph says something about us as a person and how we see things. Looking at it that way, it is a really raw and vulnerable form of talking. So quiet, but yet brimming with words.

For me, this is the perfect picture for a daydreamer. I’m immediately taken away; the wind is playing with my hair, I can feel it. I want to be there, looking at this view. I long for the mountains and the smell of vacation in the south of Europe. I want this to be my own memory, and to always remember having seen this. The picture is taken by my grandfather, on his honeymoon with my grandmother. Their relationship didn’t last and I never got to experience the love they once shared. It’s a memory that’s not mine, from a time when I wasn’t. An everyday situation I’ll never know, and can only imagine. That’s the thing with photographs; it will never be one’s own reality, only a perception set in motion.

LINN SCHRÖDER

Linn Schröder, Selfportrait with twins and one breast, 2012 . (In cooperation with Elke Rüss).

Afterimage by Clara Bahlsen:

This image has been with me for a long time, it’s so special to me. I know the photographer, we have talked about photography, but we have never talked about this image.

I really relate to Linn Schröder’s picture, maybe everyone does, this borderline situation of life and death, how it talks about fear. It is such a poetic and dramatic image at the same time, and it’s bigger than words.

I feel that I can be part of the picture, it is kind of a community thing for me. Will one breast be enough? We see this male figure in front of the kid where there is no breast, and I feel it could be my hand. That I should take part in raising these children and maybe take care of the mother as well. You don’t see her face, it’s all about the bodies. It could be my body, or your body, we could all be in this situation. I can adapt to this very moment, which is strange as it is such a special and private one. To me the picture is not about one specific mother surviving an illness - it is us, all of us human beings, taking care of each other, sharing love and fear and life and death.

Maybe, since I have a child myself, this image became even more important to me. Death is closer now, my time will end before my son’s time. Since he came to this planet thoughts like these are more present to me, I can feel time running through me. I see this in the picture, they can’t die today, they have to get through this. You only see the faces of the children, no father, no mother, only the future. They depend on adults right now, but they will be fine later.

Some images become part of my own biography. I feel that I have been there, but of course I haven’t. But still, I’m unable to erase them from my mind. Unable to ever forget. They even physically become part of my body as the pictures are stored in my brain. That is such a powerful act.

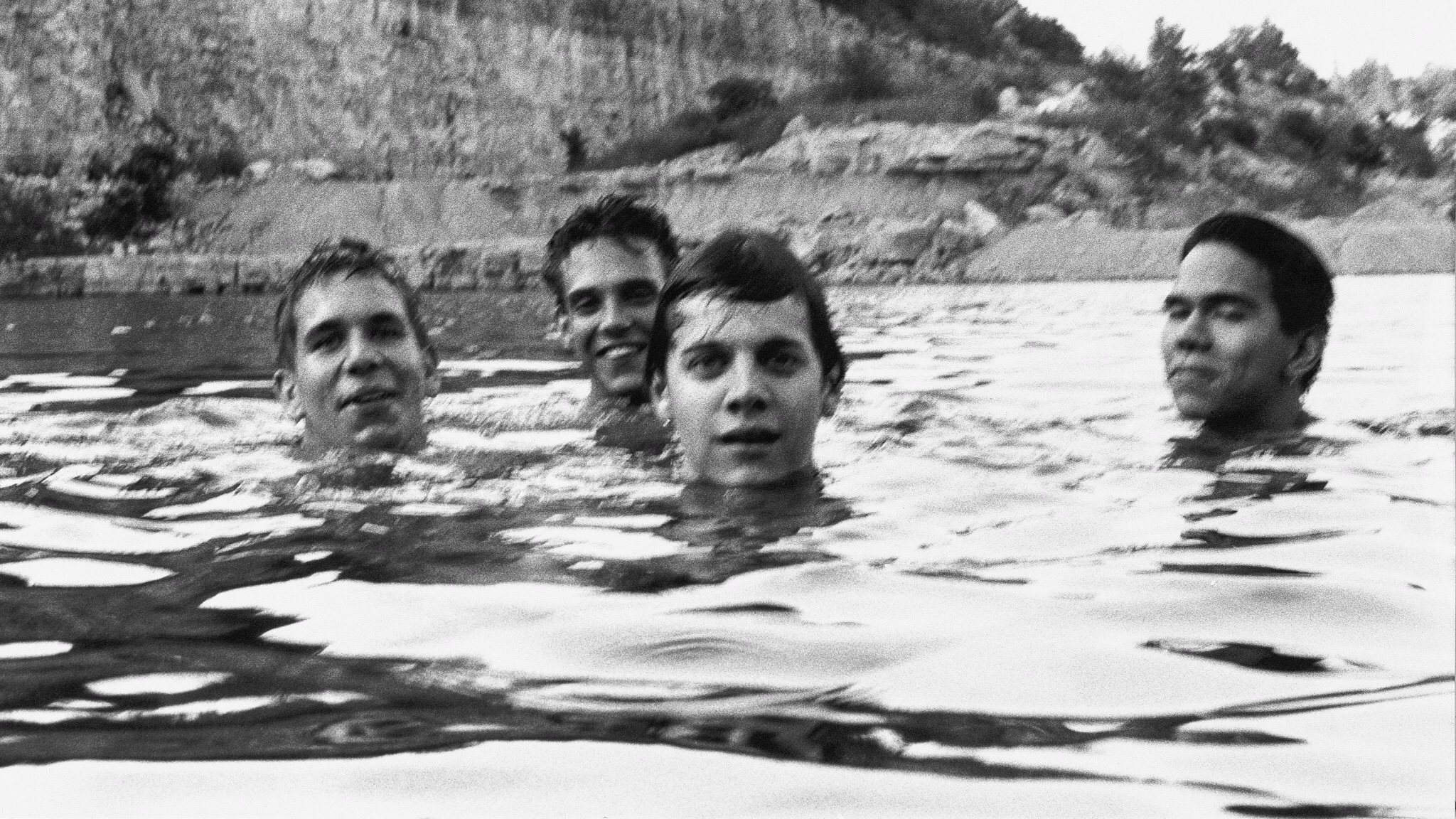

WILL OLDHAM

Spiderland cover photo, Will Oldham.

Afterimage by Marius Eriksen:

The image on the front cover of Slint’s seminal album Spiderland, taken by Will Oldham, the musician behind the various monikers Palace Music, Palace Brothers and Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, is an image that entered my life at sixteen. Browsing through CD’s in a record store, the image of four heads bobbing in a quarry gave me a strange mix of contradictory feelings, feelings of emptiness and warmth. The photograph seemed so familiar, like I had experienced that exact moment myself. It felt like I was standing in an alternate universe looking at a moment that I had been part of in some strange way. I’ve tried several times to recreate this image in the many creeks and rivers of my hometown without any success. I never managed to create the same type of eerie feeling. I guess some moments just aren’t easily reproduced, or maybe some moments aren’t meant to be reproduced.

Looking at the four persons half submerged in the water with their faces half-smiling, it felt like they were staring right through me, like there was some dark Lovecraftian force lurking in front of them and that it was hanging over me. Could their gaze be an omen? An omen that my salad days were drawing to a close? That the future was going to be lined with darkness and destitution? I had no idea what to make of it, but my mind was racing just looking at that cover. It felt like it took some time before my mind managed climb out of the existential void this image hurled me into and my focus started to shift. Looking at that image again, their gaze wasn’t longer an unsettling gaze, it offered consolation. Their smirking faces provided a sort of stoic consolation, a promise that no matter what lies ahead, the bottom line would be that things would nonetheless turn out to be OK.