PROTESTIMAGE

Found via Feminist News on Facebook. Photographer unknown.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There’s an image from the recent protests in Poland that I can’t stop thinking about. A woman stands in the middle of a street, in the midst of a demo, wearing a mask and waving a Pride flag in all the smoke and chaos. She seems angry, which is understandable and relatable. Why shouldn’t Polish women be able to decide what happens in their own wombs? It’s 2020 and I can’t believe that we’re here again, with the election of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court putting the American right to abortion in danger, and so the image from Poland hits me. I’m with her in this protest. I’m with her on the issue of choice. It’s vital to me that every single woman gets to decide what to do with her own body. And it’s terrifying how this choice is still being threatened. It reminds me of the image that went viral some years ago, from another protest, of a woman in her sixties holding the sign: ‘I Can't Believe I Still Have To Protest This Fucking Shit.’ She’d obviously done this before. We know that we, and our daughters, stand on the shoulders of our mothers, their grandmothers, who fought for the right to choose. And yet here we are again.

In 2017, I co-curated an exhibition called Subjektiv at Malmö Konsthall showing the work of Josephine Pryde among others, whose series It’s Not My Body shows MRI scans of a foetus in the womb montaged onto colour landscape shots. Pryde hadn’t been intending to take part in any ‘urgent response’-type exhibitions at that specific political juncture, but what caught her attention was another chance to NOT say how it feels to be a pregnant individual. She was interested in describing a shared material state, and included these pieces in the exhibition because she thinks human reproduction is extraordinary and that the history of women as property, as the designated site of reproduction, still haunts our popular mythologies and cultural exchanges. How these ghosts return, how they duplicate themselves and occupy imaginations, is a matter of intense relevance to her, and also to us four years later in these very trying times. So all these thoughts and feelings arise in my mind when looking at the Polish woman waving her flag in Warsaw. I do hope that we won’t have to see images like this in the years to come.

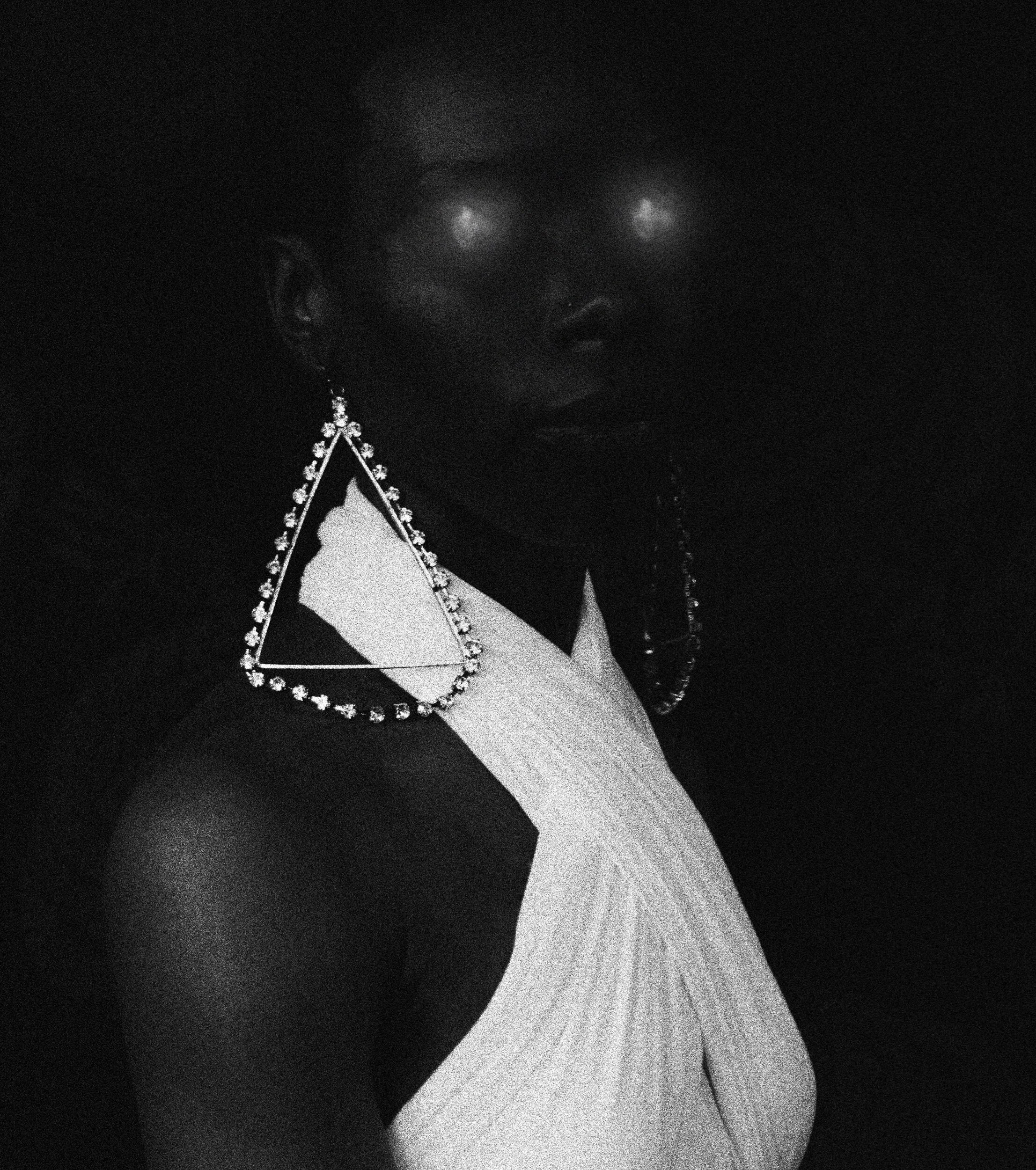

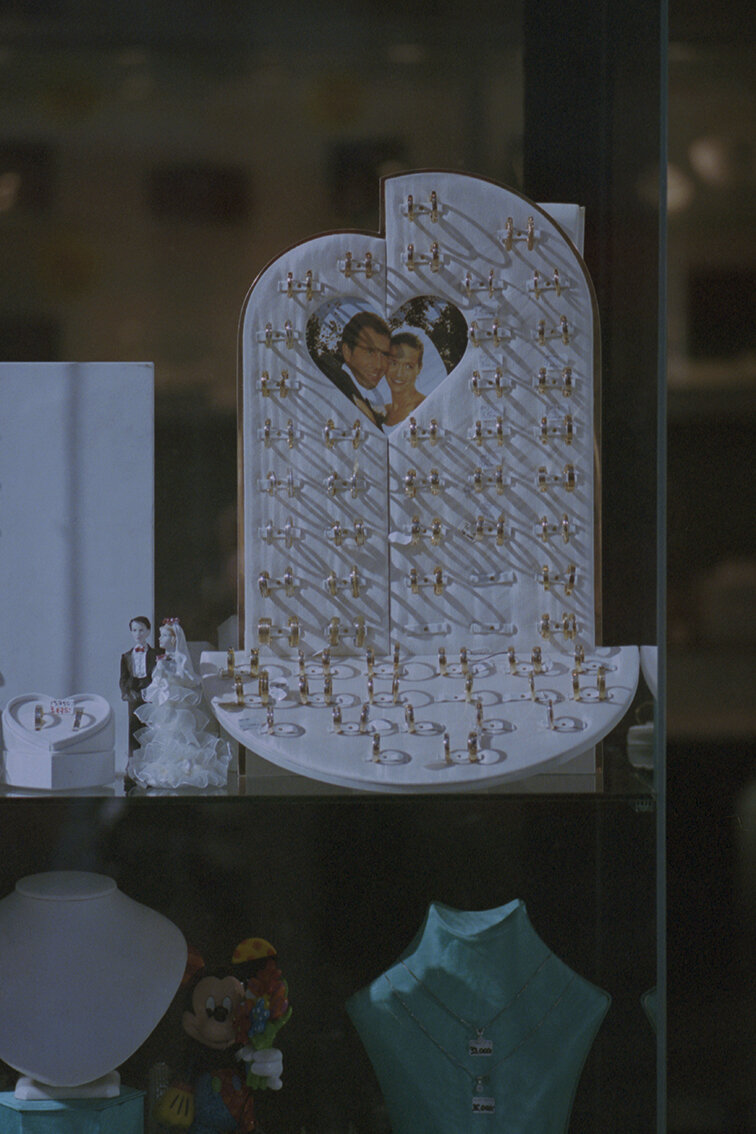

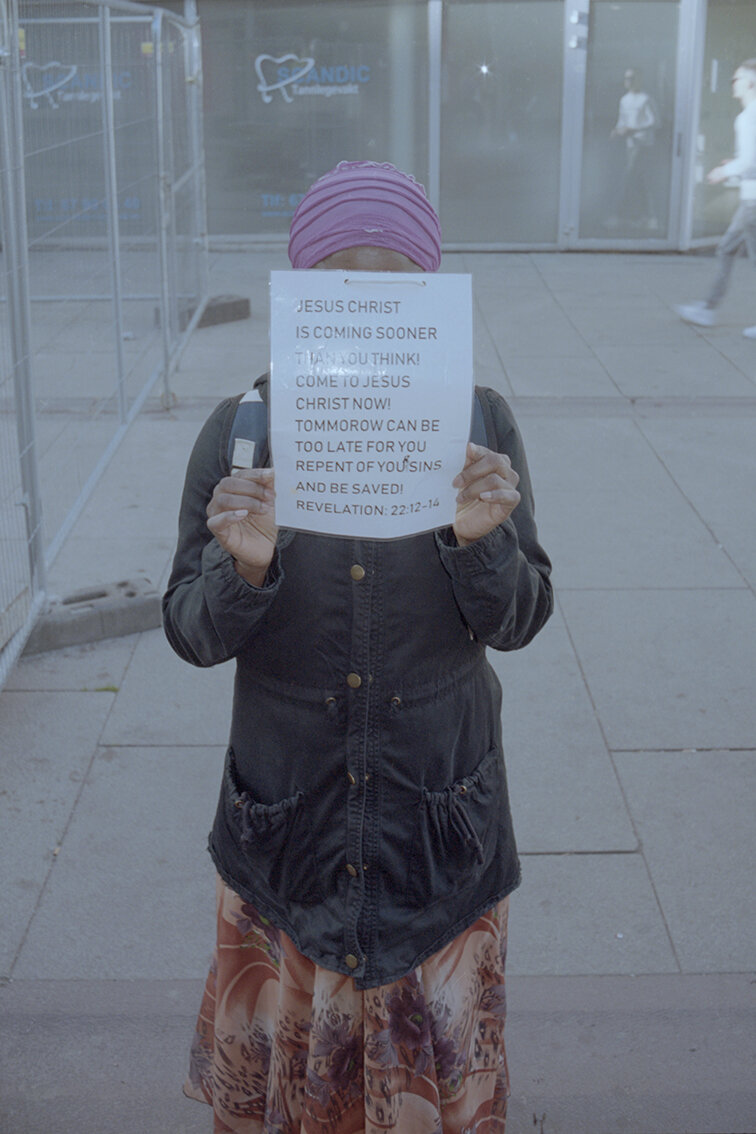

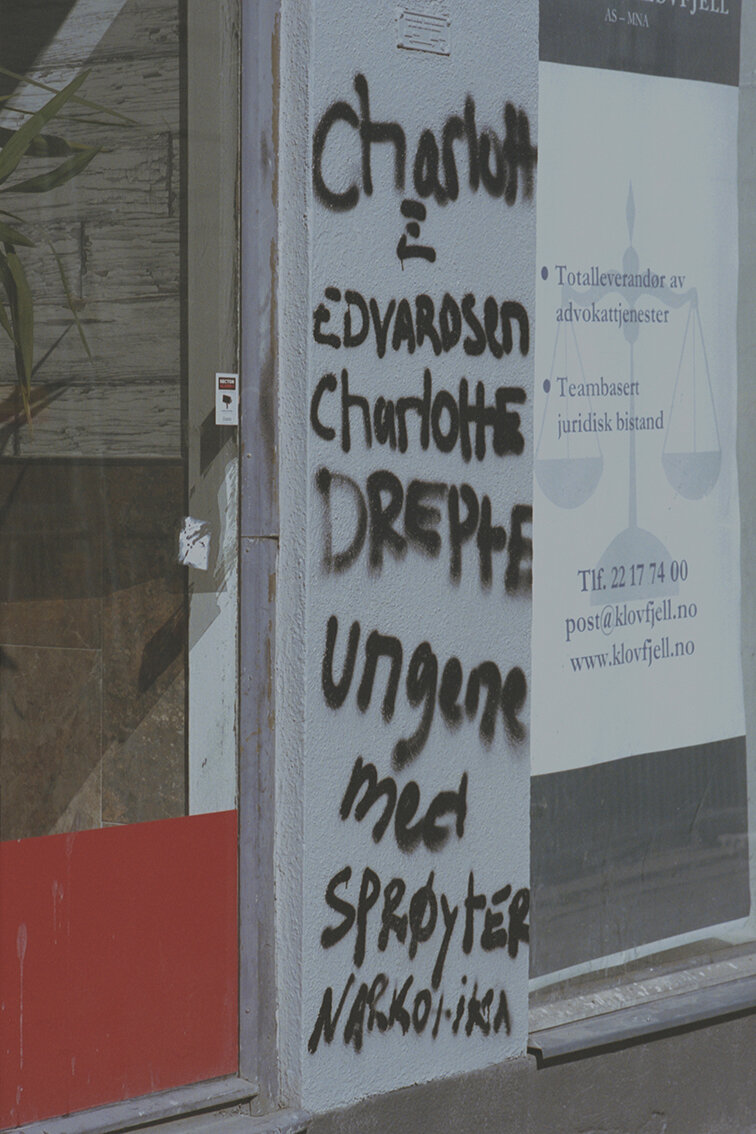

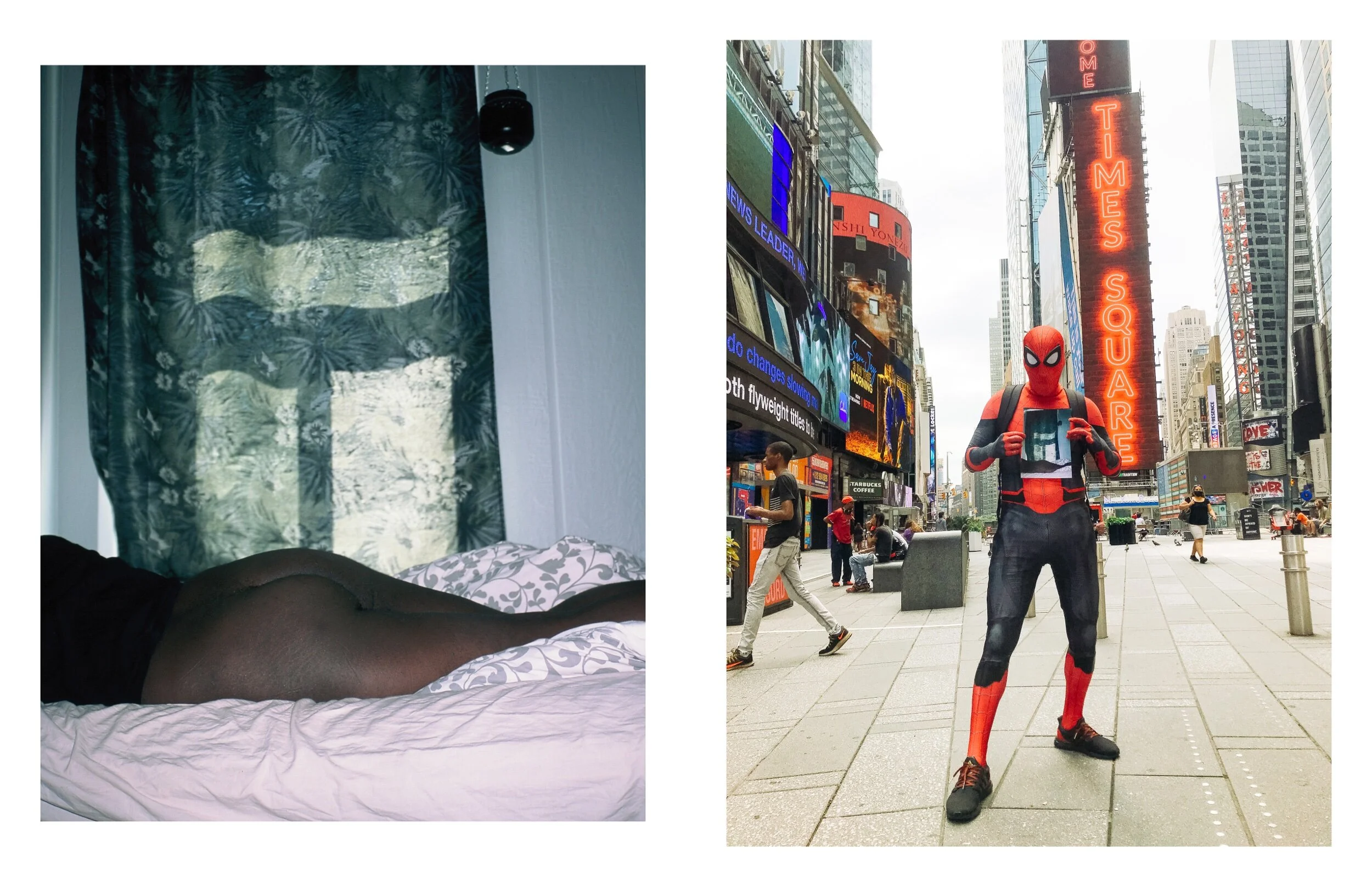

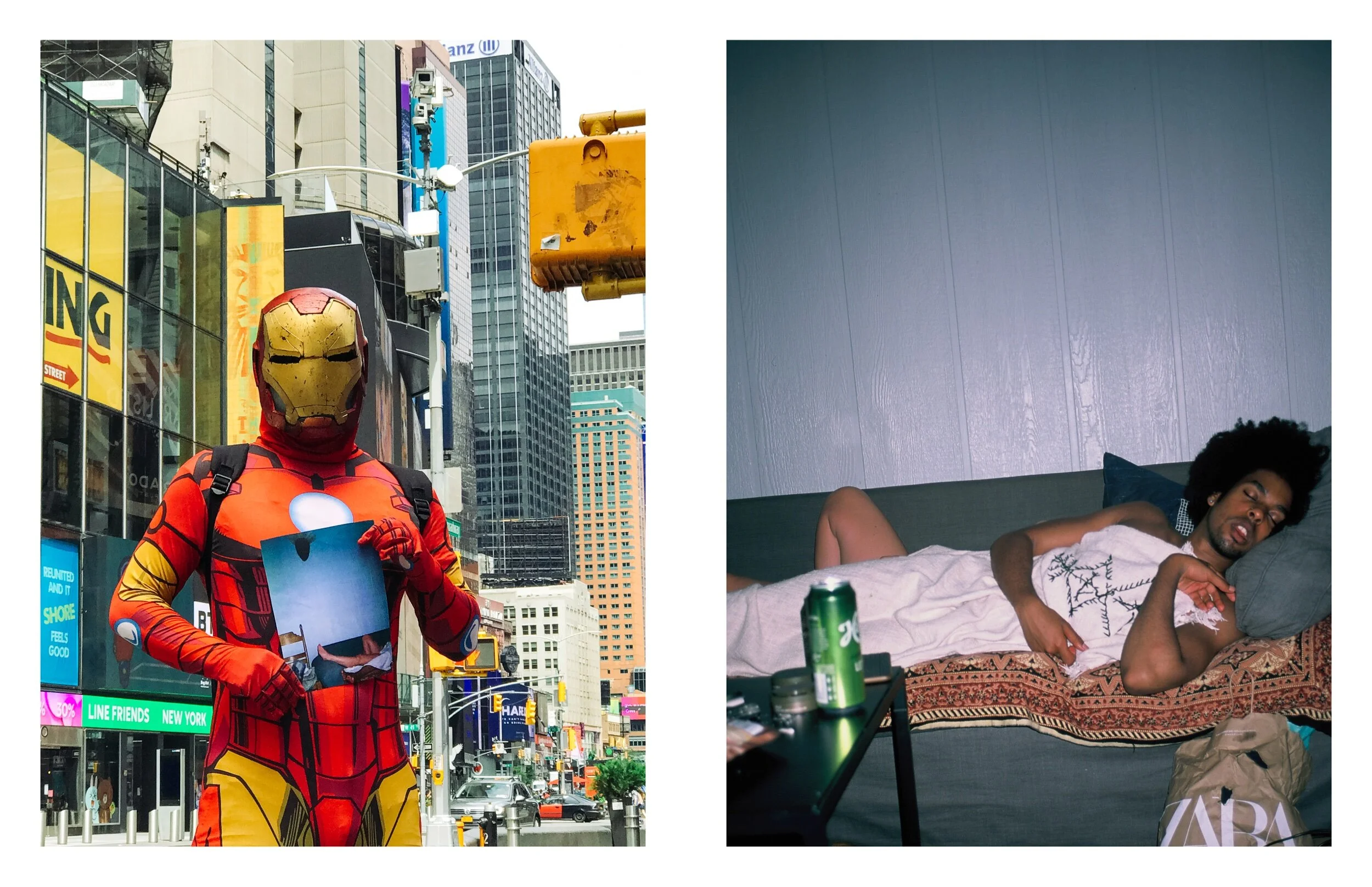

SOFIE AMALIE KLOUGART

Immediate Vicinity

Here in Storgata, Oslo, we either have to stand close to each other or shout to be able to communicate. Storgata is being upgraded, according to the website of Oslo Municipality, and in the early hours of the day the noise from the construction work is constant. They’re building wider sidewalks, new tram tracks, more tram stops, a new water and sewer network. I don’t recognise Storgata on the architects' renderings of a future street. In the drawings, Storgata is an avenue with blossoming cherry trees and people on the move. No one is begging or injecting heroin. No large groups of misfits in front of the Gunerius shopping centre, no police, guards or social workers. Here, everything is neat and tidy.

For two years I’ve lived in Norway, and for just as long I’ve wanted to photograph the area where I live. I’m documenting my immediate vicinity and some of the people who characterise this urban space before it disappears for good.

CHRIS KILLIP

Simon Being Taken out to Sea for the First Time since His Father Drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, negative 1983; print 2014, Chris Killip, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of and © Chris Killip. Image from the exhibition Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante, May 23-August 13, 2017, Getty Center.

Afterimage by Matthieu Nicol:

What image do I have in mind at the moment? It’s difficult to give a quick answer to the question Objektiv has proposed. In my work as a photo editor for the daily press, I see thousands of shots on my monitors every day. This ocean of images, mainly from agencies, formatted, and in the end, very similar, does not help with digestion. Rather than writing about press photos, I want to talk about images or series of images from exhibitions or festivals that has made an impression on me lately. But when squeezing, nothing came out. So I put this question in the corner of my mind for a few weeks, and let it decant. Regularly, like the backwash of a wave, a handful of shots came back; sometimes engulfed but eventually graved in my visual memory. Nothing new, nothing current. So I allowed myself to slightly modify the question: which image, absorbed a long time ago, has stayed etched in my memory and resurfaced regularly?

Among the icons of my “imaginary museum”, there is one that haunts me. A terrible image of infinite sadness but of absolute relevance. In Madrid, February in 2014, an exhibition soberly entitled Work, a retrospective of the work by Chris Killip, was presented at the Reina Sofia Museum. I knew the photographer’s work, and several of his series on the impoverished communities in northern England, the victims of deindustrialization in the early 1980’s in the beginning of Thatcherism. I’d seen them online or in catalogues, notably In Flagrante (1988). But this image was unknown to me because it was absent from the books.

I don’t want to linger on the formal composition of the scene, the position of the body and the closed eyes of the little boy in his Sunday best, floating in adult clothes, his head bent on the line of the horizon, the slight oscillation of a swaying boat, of which only the bow is in the frame. A form of a closed room, without doors or windows, perfectly executed. I would, however, like to emphasise the caption: Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Everything we need to know is there, in this exact wording. A subject, described by his first name, the reason for his presence, a place, a date. 18 words.

Although the image alone can produce this piercing effect, this “punctum” dear to Barthes, allowing the observer to appropriate it beyond all knowledge, code or culture; the caption gives us information that is essential to our comprehension. What is mind-blowing in this link between text and image is that it reveals the evidence of an extraordinary situation. It enables an immediate comprehension of the degree of commitment the photographer has with his subject. Killip’s approach is unique, the author is distant, out of frame and at the same time, completely immersed in a poignant intimacy. Only the construction of a long- term relationship with this tiny fishing village named Skinningrove, where he documents the daily life of its inhabitants, allows him to produce a scene like this and show it to the world.

With an image so prone to allegory, one could make it say a number of things: a rite of passage into adulthood, filial love, sadness and sorrow. One could also enter into dialogue with other images, I’m especially thinking of the one of Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach in September 2015. This “shock image” that rapidly went worldwide, became the tragic symbol of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean. In this reversed perspective we see a small, drowned body and not the survivor, his father, who subsequently testifies of the drowning to international media. Within me, the connection is evident: in my visual memory, these images are contemporary, and as a father of two children the age of Simon and Alan, they move me particularly. But the comparison stops there. We cannot suspect Killip of voyeurism. His restraint, his sense of propriety, his engagement, his empathy are all entirely resumed in this image and its caption.

During a presentation at Harvard University in 2013, where he taught from 1991 to 2017, Killip confides his discomfort on the use of this scene and a few other images taken that day: “I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... ». And indeed, the author dismissed the image from the two editions of In Flagrante (1988 and 2015). During a later conversation held in 2017 at the Getty center in Los Angeles, he clarifies: “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act’, and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

En français:

Quelle image ai-je en tête en ce moment ? Il m'a été compliqué de répondre rapidement à cette question, à l’invitation d’ Objektiv. Dans mon travail d'éditeur photo pour la presse quotidienne, je vois passer plusieurs milliers de clichés par jour sur mes moniteurs. Cet océan d'images, principalement d'agence, formatées et finalement fort similaires n'aide pas à la digestion. Plutôt que de photos de presse, j’ai alors cherché à parler d'images ou de séries m’ayant marquées dernièrement dans des expositions ou des festivals. Mais en pressant, rien ne sort. Et j'ai mis cette question dans un coin de ma tête durant quelques semaines, et laissé décanter. Régulièrement, tel le ressac, reviennent une poignée de clichés parfois engloutis mais finalement gravés durablement dans ma mémoire visuelle. Rien de neuf, rien d'actuel. Alors je me suis permis de modifier quelque peu la question : quelle image, assimilée depuis longtemps, est restée gravée dans ma mémoire et refait surface régulièrement ?

Parmi ces icônes de mon « musée imaginaire » il y en a une qui me hante. Une image terrible, d'une tristesse infinie, mais d’une justesse absolue. C'était en février 2014, à Madrid. Une exposition sobrement intitulée Work, rétrospective du travail de Chris Killip présenté au Musée Reina Sofia. Je connaissais le travail du photographe, et plusieurs de ses séries sur les communautés paupérisées du nord de l’Angleterre, victimes de la désindustrialisation à l’aube des années 1980, début du Thatcherisme. Je les avais vues en ligne ou dans des catalogues, et notamment In Flagrante (1988). Mais cette image m’était inconnue, car absente de ces ouvrages.

Je ne souhaite pas m’attarder ici sur la composition formelle de cette scène, la position du corps et les yeux fermés de ce petit garçon endimanché, flottant dans des habits d’adulte, sa tête courbée crevant la ligne d’horizon, la légère oscillation d’une barque qui tangue et dont seule la proue est dans le cadre. Une forme de huis-clos, sans portes ni fenêtres, parfaitement exécuté. Je voudrais en revanche insister sur sa légende : Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Tout ce que l’on a besoin de savoir y est dit, dosé au mot près. Un sujet, décrit par son prénom, la raison de sa présence, un lieu, une date. 18 mots.

Si l’image seule peut créer cette fulgurance, ce « punctum » cher à Barthes qui permet à celui qui l’observe de se l’approprier, au-delà de tout savoir, de tout code, de toute culture, la légende ici donne une information essentielle à sa compréhension. Ce qui est sidérant dans ce rapport texte-image, c’est qu’il révèle l’évidence d’une situation exceptionnelle. Il permet de comprendre immédiatement le degré d'engagement du photographe avec son sujet. La pratique de Killip est singulière, l’auteur est distant, hors cadre et en même temps, totalement immergé dans une intimité poignante. Seule la construction d’une relation de long terme dans ce village de pêcheurs nommé Skinningrove dont il documente au long cours la vie quotidienne des habitants, lui permet de produire une telle scène et de la donner à voir au monde.

On pourrait faire dire beaucoup de choses à cette image qui se prête facilement à l’allégorie : celle d’un rite du passage à l’âge adulte, de l’amour filial, de la tristesse et du deuil. On pourrait également la faire dialoguer avec d’autres. Je pense en particulier à celle d’Alan Kurdi, ce garçonnet syrien échoué sur une plage turque en septembre 2015. Cette "image-choc", qui a rapidement fait le tour du monde, est devenue le symbole tragique de la crise des migrants en Méditerranée. Dans un retournement de perspective c’est ici un corps de petit noyé, mort, que l’on voit, et non le survivant, son père, rescapé, qui témoigne après-coup de la noyade auprès des médias internationaux. En moi, le lien est évident : dans ma mémoire visuelle, ces images sont contemporaines, et en tant que père de deux enfants de l'âge de Simon et d'Alan, elles m'émeuvent particulièrement. Mais la comparaison s'arrête là. On ne peut pas soupçonner Killip de voyeurisme. Sa retenue, sa pudeur, son engagement, son empathie sont tout entiers résumés dans cette image et sa légende.

Lors d’une présentation à l'Université Harvard en 2013, ou il a enseigné de 1991 à 2017, Killip confie sa gêne sur l'usage qu'il pourrait faire de cette scène et des quelques autres images réalisées ce jour : « I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... » Et de fait, l’auteur a écarté cette image de ses deux éditions d'In Flagrante (1988 et 2015). Lors d'une conversation plus tardive, tenue en 2017 au Getty Center de Los Angeles, il précise : “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act,’ and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

This text is translated by Anja Grøner Krogstad.

ÅSNE ELDØY

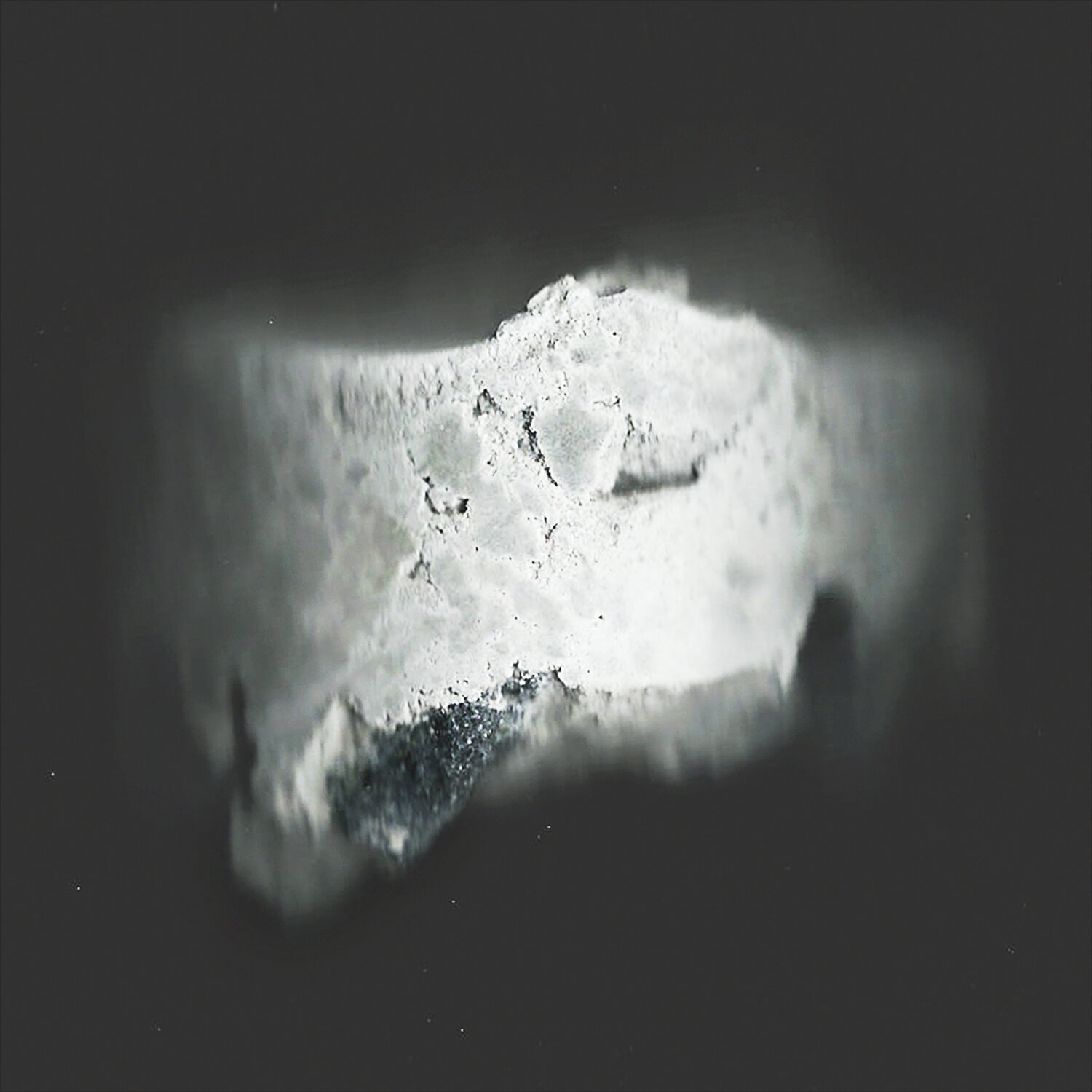

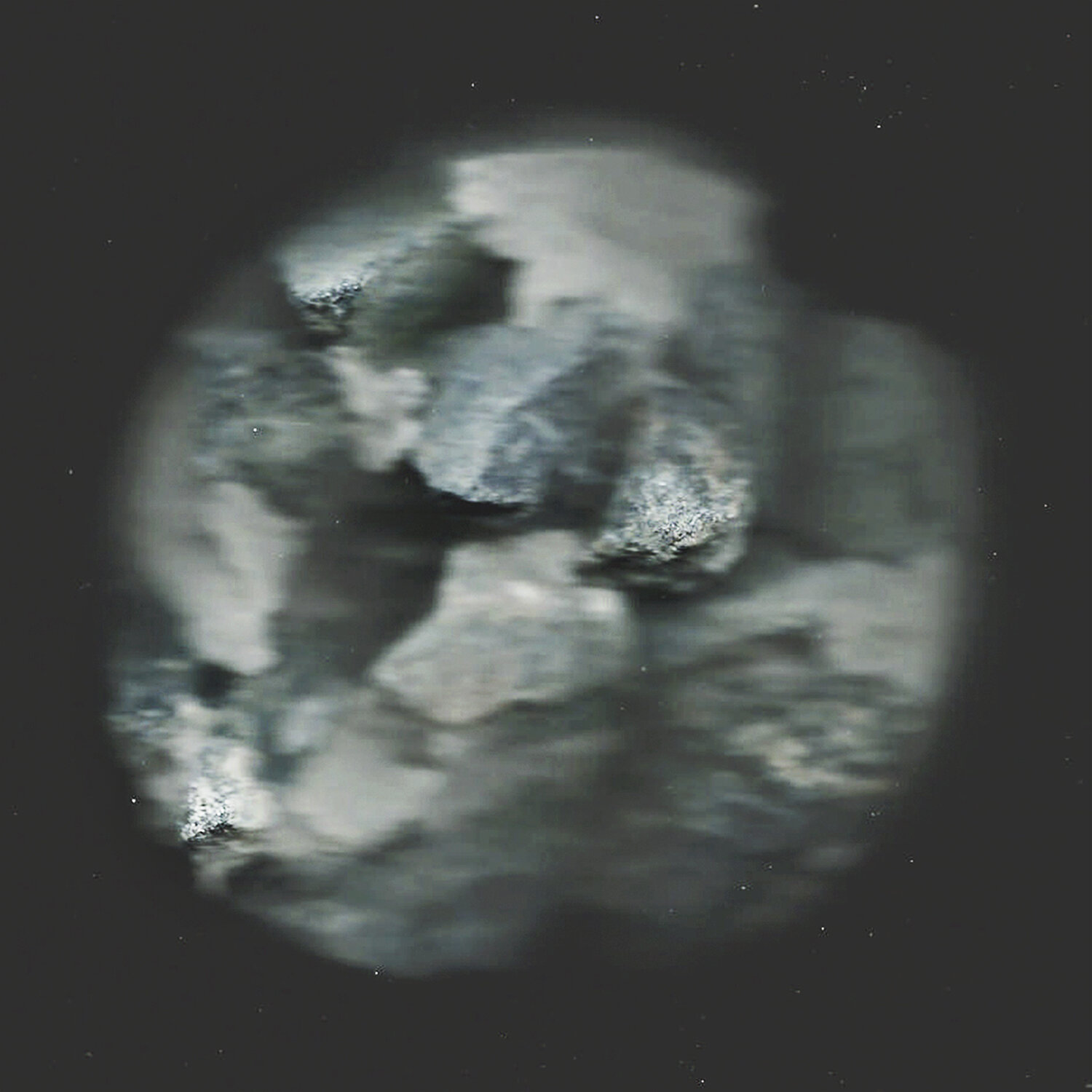

Exercises in Structure, part 2.

Concrete fragment A, satellite series, I-III (2020). Concrete fragment B, inside series, I-III (2020). Quarry no. 06, no. 23 & no. 24. (2019).

Time is now longer than other times. It moves slower than it used to. It’s a time for practice. Recurrence. Repetition.

ANTHEA BEHM

I started making photographs when I was in high school through an after school darkroom class. It was a volatile time in my life, and the darkroom provided a space of refuge.

My high school darkroom, like many community darkrooms, had a series of enlargers in a row that were separated by dividers. Working in the dark at one of these stations gave me much needed space where I could pause and take cover. As in many such darkrooms, the trays of chemicals where you process your prints were shared. When it was time to put my paper through the chemistry, I moved from a singular, solitary position into a communal one. This was a space of gathering, and also of care: when moving your prints through the trays, you needed to be aware of affecting other prints that were also mid-process.

This separation of space was not absolute. Even when you’re alone at your enlarging station, you must be mindful of your community. For example, you must ensure that you don’t turn on your enlarger with the negative carrier open, which could mistakenly expose your neighbor’s paper to light. And even though—like much human activity—analogue photography can be destructive to the environment, the rules of the darkroom help minimize harm; for example, never pouring fixer down the sink.

Today, I am processing prints in my studio darkroom in Gainesville, Florida, where I am also sheltering in place. I work alone, but within this distancing there is also connection and care. Our experiences and our relationships—to ourselves, each other, and the world—are not fixed in a final photograph. They are the entire process.

MELANIE KITTI

I found so many claws

Rip rip

Found them on the lawn where they

put rips in a pair of sneakers from below

Drank milk from various udders

and I paid a witch to do it

I paid to watch her drink

She left the udders dripping

ripped her cheeks with one of the claws

I filled her third eye

I whipped a pigeon on the breast

It was about to put its jaw around

a potato on the table edge

Frayed at the edge

Teeth gnashed

I made the pigeon feel shame

Then I caressed the pigeon’s wing tips

with my finger tips

was fluent in words that

counted backwards, three

I caressed the wing tips back and forth and

I put pressure on the vein’s end

I dropped all of my peas in the background

Turned around

I turned my peas around the wrong way

Picked too many peas to bead on the thread

and I spent time in the fog

I spent time with the pigeon and the fog froze

I kept a very tight grip on the thread end

I collected the fog and I weighed it

Lost my grip

Ran between my fingers and my head shrunk

Mash all over

I whipped the pigeon once again

The pigeon’s jaw popped

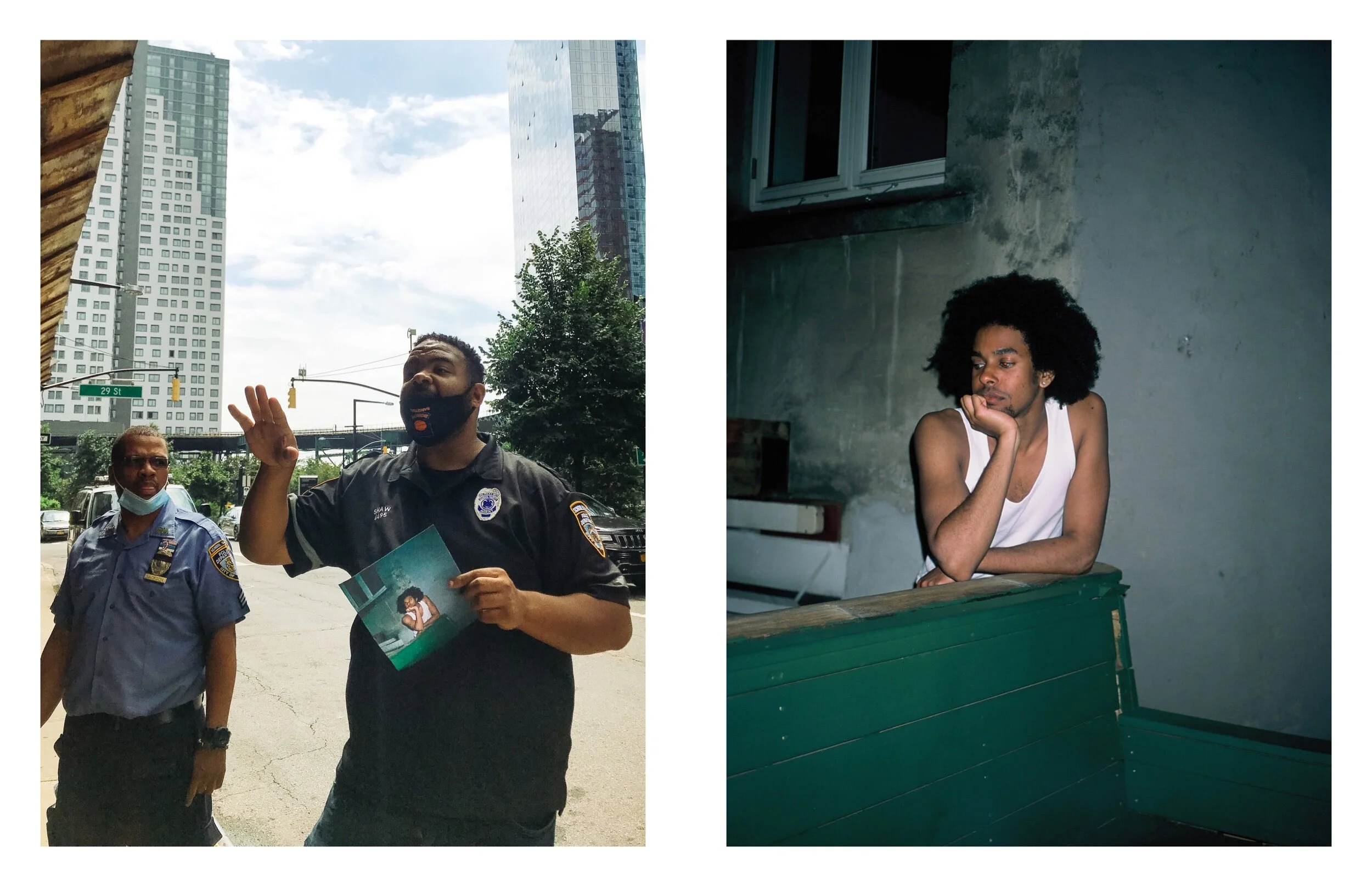

JEET SENGUPTA

As the situation around the world gets worse every day with the news of the rise in deaths, I’ve become paranoid about losing my parents. Even though we’re living together, I cannot get this fear out of my head. A number of times, I’ve imagined that they are dead.

In the early stages of lockdown, I used to check my parents’ temperatures every other day. The seriousness of the disease and its ability to spread within the community has made me doubtful of the people on the streets, even neighbours and friends. Every morning, half awake, I call out to my mother from my room to get her response, to know she’s still there. When I hear her voice, I go back to sleep again. Somehow this makes me feel safe, even in my dreams. But I’m scared that one day, I’ll hear only silence.

It’s been over two months now. The fear of the pandemic has now also become fear of people. I am worried that I will isolate myself from the world even after the lockdown ends.

DAVID GEORGE

16th APRIL 2020.

AS A LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHER MY PRACTICE HAS BEEN COMPLETELY CURTAILED BY LOCKDOWN SO I HAVE TAKEN TO RECORDING MY DAILY 5AM DOG WALKS AROUND HACKNEY, LONDON ON AN OLD IPHONE 5 .

SARAH MEADOWS

I'm thinking about spring, all of the spring happening that I can't experience. Fertility, growth, and life cycles are cycling onward outside of my house and I wish I could be out there.

Frog and salamander egg images from google searching in my room. May 13, 2020.

THORA DOLVEN BALKE

I look forward to the time I can step outside this moment and find a language to describe it from a distance, right now it just swallows me whole.

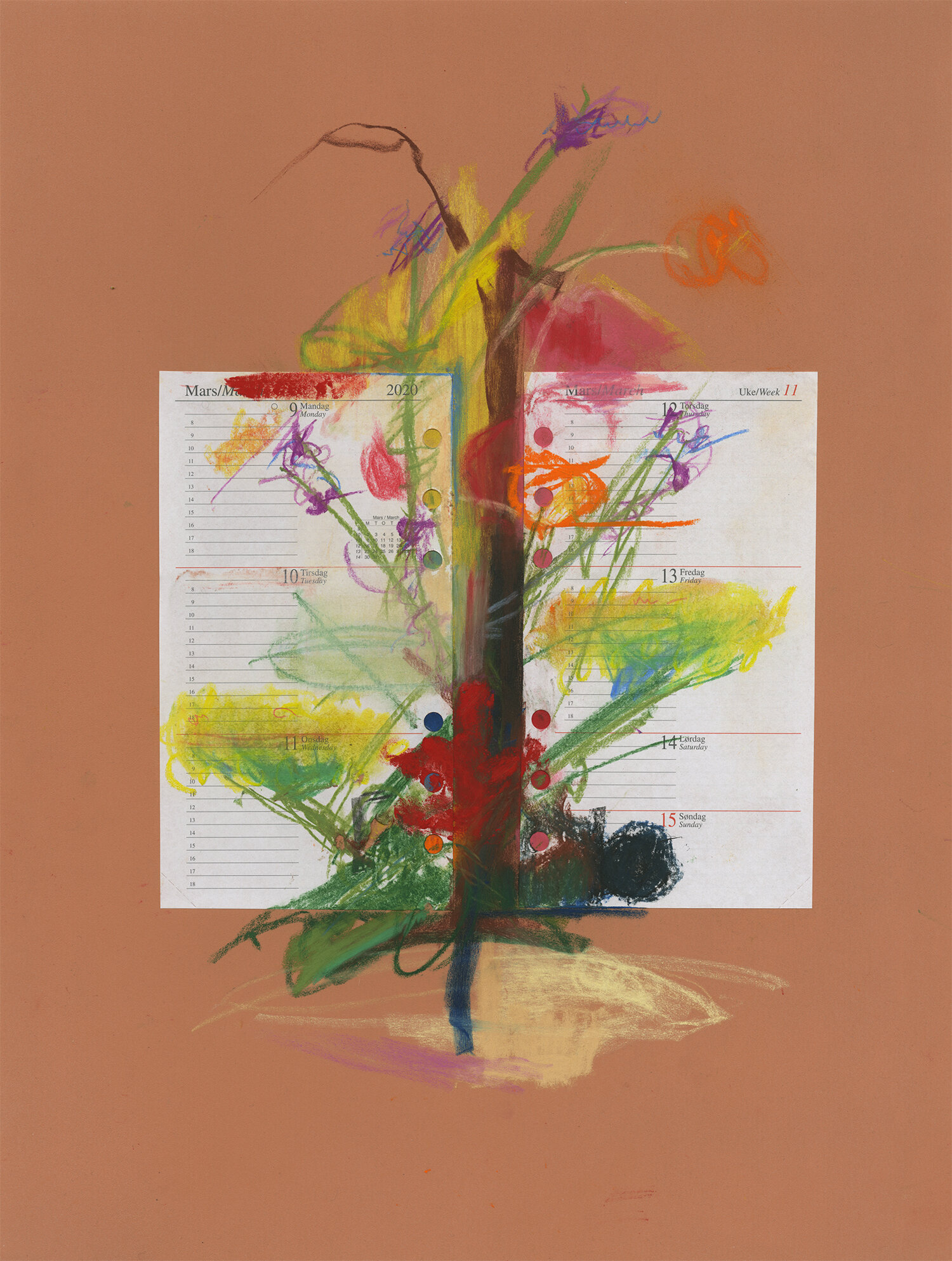

CAMILLA REYMAN

Camilla Reyman, What day is it?, 2020.

I have been debating with my self for years wether my obsession with the square was ok, and in these times of confinement I finally feel it is an appropriate subject/object to engage in ◼️◼️◼️.

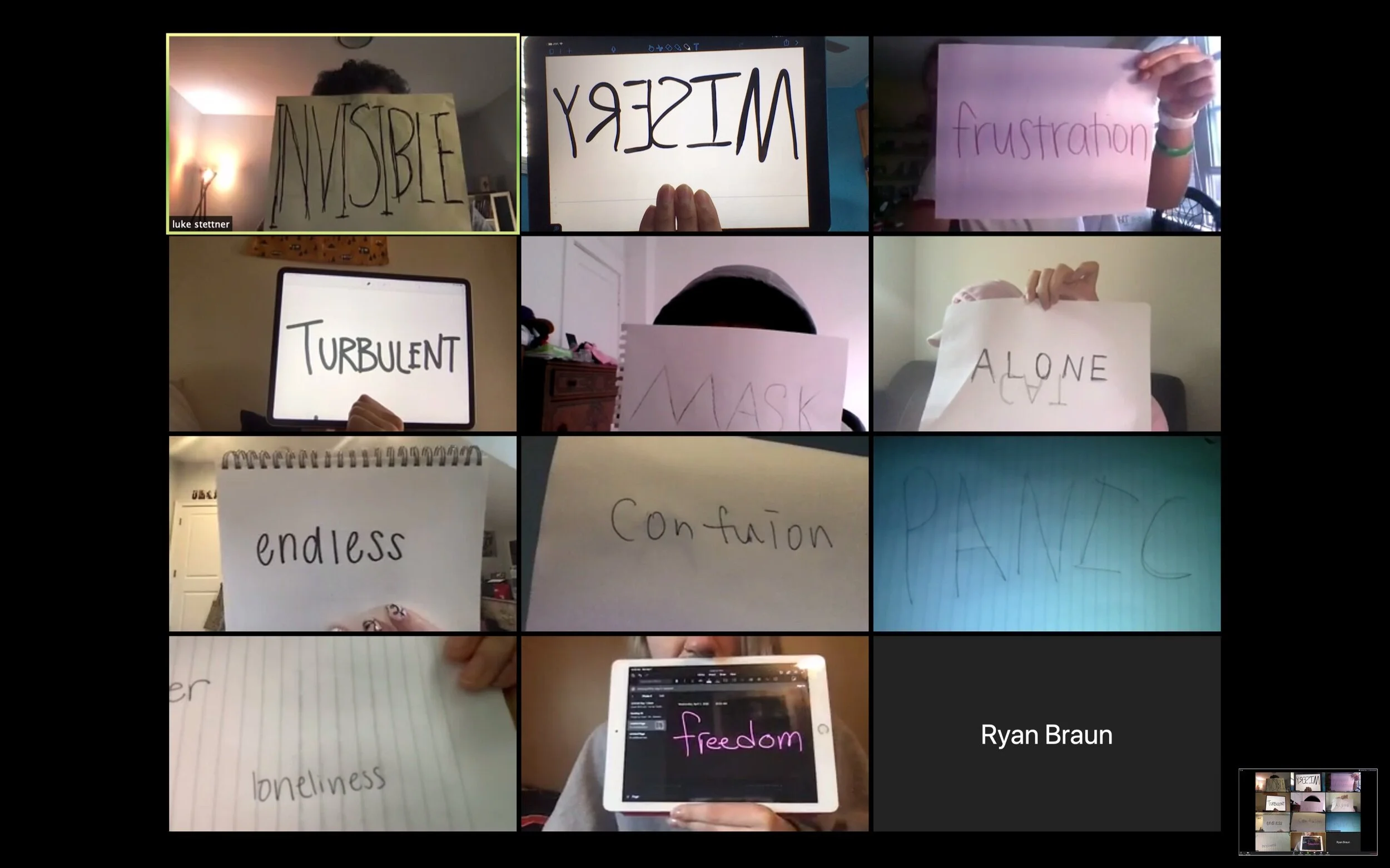

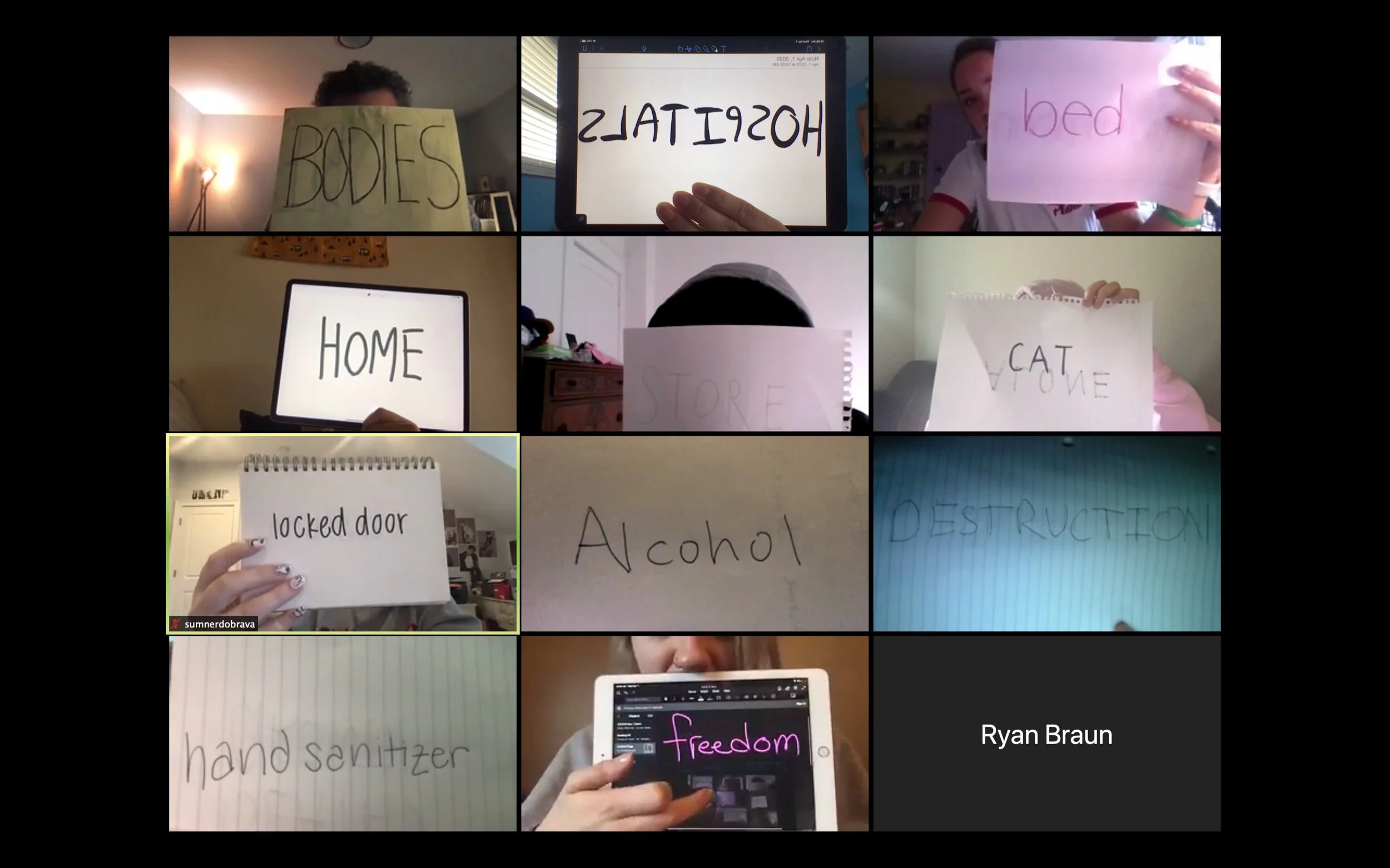

LUKE STETTNER

Luke Stettner collaborated with his darkroom photography students from Ohio State University during a zoom class session. Together and at once across their screens, they held up concrete and abstract nouns in response to the time we are living through. Grace Advent, Enrique Arayata, Ryan Braun, Margaret Derrig, Sumner Dobrava, Sarah Estes, Ella Feng, Jeramey Frelin, Jet Ni, Luke Stettner, Connor Yoho, Zhuoran Zhang.

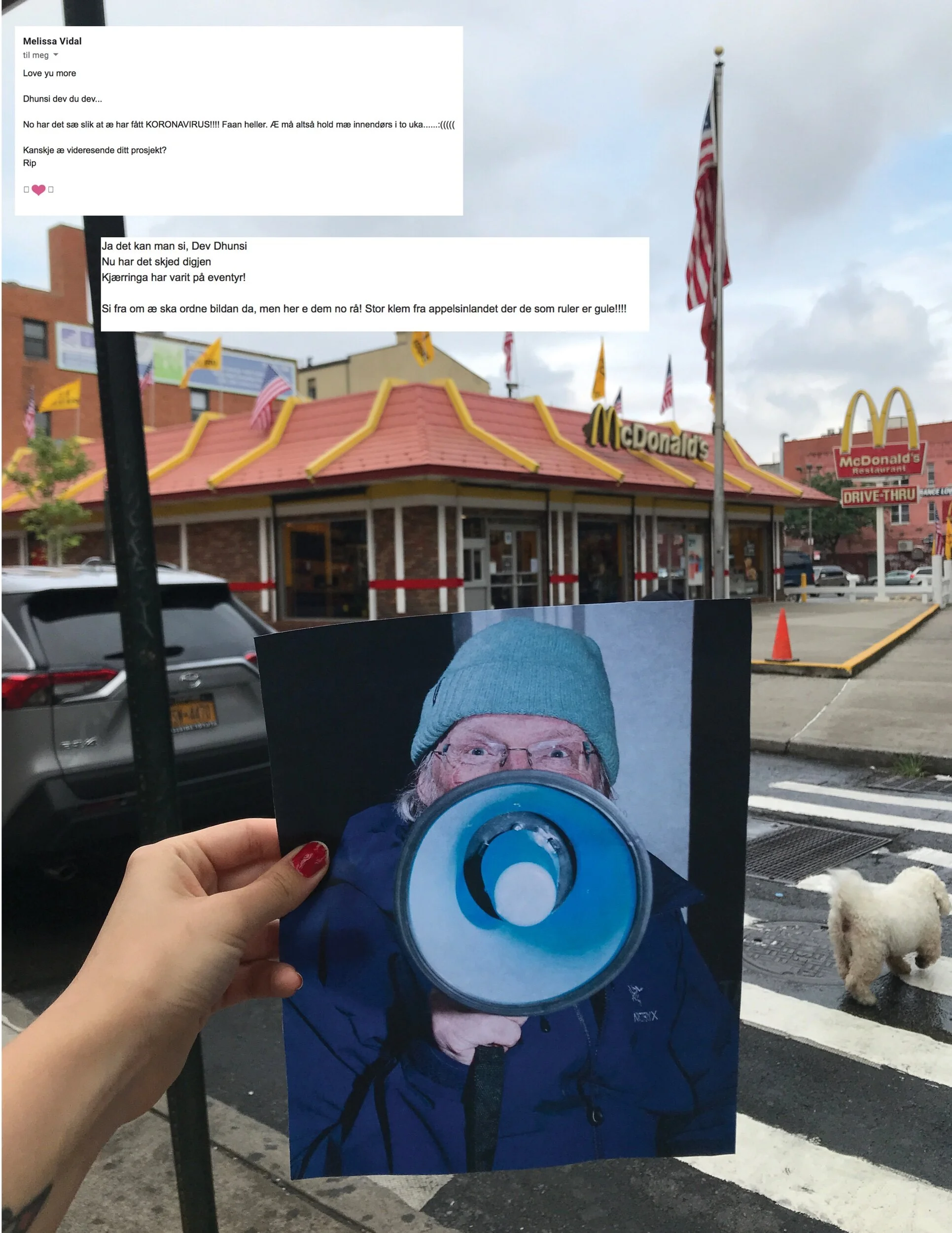

SOLVEIG LØNSETH

Visual Wanderings

Objektiv has initiated a new series of works, Visual Wanderings, made especially for our online journal. We are inviting photographers from all over the world to create art that responds to our new situation: what does the lock-down mean for their work, what is important for them to convey, and what are their reflections on the time to come?

Contributions can take any form, from a photograph to words, a series of pictures or a meme. Each photographer will then be asked to pick another artist to create a work. The works don’t have be related to each other, but we want them to reflect how the virus informs their work and life. In this way, we will create a visual dialogue that runs across many different countries, in order to get a bigger picture of how this crisis and its aftermath are playing out for artists all over the world.

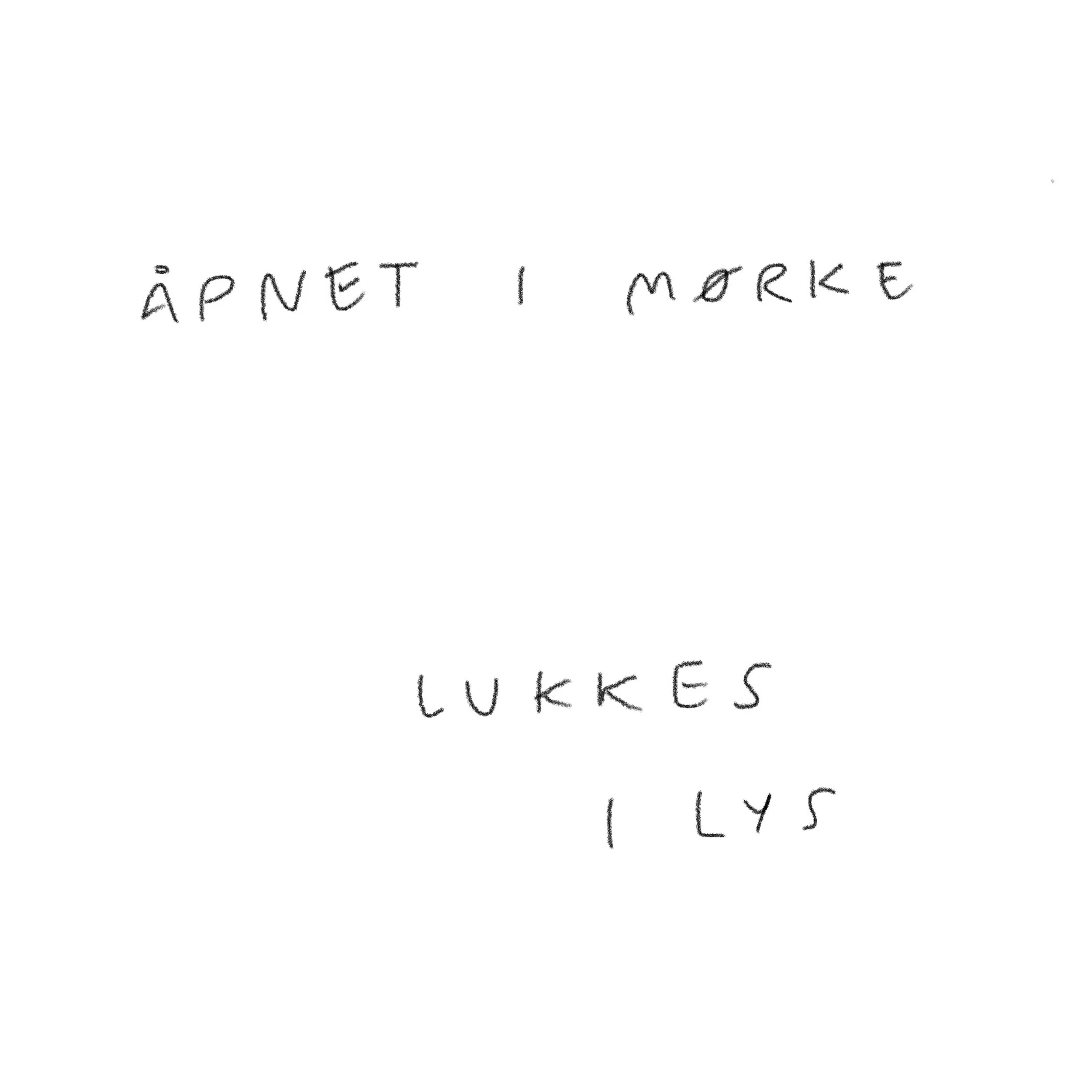

To present these visual wanderings, here is a photographic text by Solveig Lønset. (Opened in the Dark, Close in Light.) Take care.