INDER SALIM

Inder Salim, We All Are Women’s Issues, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

In the recently opened exhibition Actions of Art & Solidarity at Kunstnernes Hus (The Artists’ House) in Oslo, there is one image that embodies the title perfectly: We All Are Women’s Issues by Indian performance artist and poet Inder Salim. The photograph is from a performance by Salim in Bangalore, India, in 2003. Salim made himself into a walking billboard to protest against violence against women, using the double meaning of “issue” to show how everyone should take a stand against gender-based violence, and also that all humans come from women. As he writes in an email to me: ‘It was indeed a day-long walk on the roads in Bangalore City in 2003. There was no video possibility in those days, but I got some clicks by friends who accompanied me.’

At that time, he and his colleagues put up around 500 posters in Bangalore, and later on buses and walls in Delhi where Salim currently lives. The poster was also used by the women’s police department in Bengaluru, and by Vimochana, a NGO working for women's issues. Salim used the image as his business card for a long time, and it was also printed on a banner of about four and a half metres. ‘The situation in India, the unfortunate treatment of women’, Salim writes, ‘particularly in rural areas, is very disturbing’.

For the past 30 years, Salim has worked tirelessly within the genre of art as activism, using video and photography as well as other channels to make us look again at the world in which we live. His work deals with bodies, sexuality and gender & queer politics. Last fall Ishara Art Foundation invited to the exhibition Every Solied Page where Salim made a series of eleven different performances under the name Every Page Soiled, to be enjoyed here. As he explains his work: ‘Performance art is not body-centric, but revolves around material and subjectivities of all kinds in our respective presents.’

The exhibition’s press text claims that: ‘solidarity has re-entered the global zeitgeist with resounding force in the last decade. It has driven new thinking focused on countering systemic failures and outright abuses related to climate, economy, surveillance, health, gender and race amongst other issues.’ And it continues: ‘Actions of Art and Solidarity considers the central role that artists play within this historical shift in the new millennium, drawing parallels to synergic cases of the twentieth century.’ Looking at Salim’s career, solidarity has always been present in his performances: ‘Doing posters from my own pocket money was my passion in early days. Nowadays, I put up flags from my terrace with text to highlight different topics in our current situation.’

The latest, from five days ago, has a very simple message: ‘I love you.’

VILDE SALHUS RØED

The Same Sun

Sun prints from hikes in mountains not far away, but closer to the sun, together with Una 4 1/2 years old, in the early spring of 2020, when time and days began to flow.

INGRID EGGEN

Installation photo by Ingrid Eggen of her Tranquilshiver #2, 2020.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This weekend, Ingrid Eggen opened the show CLAIM YOUR SUPERIOR BONE together with Admir Batlak at the small artist-run gallery Noplace. Her three new photographs made me recall a recent FaceTime conversation with a dear friend and colleague who had just attended a vernissage and needed a debrief. She said everyone there had been acting weirdly, and wondered if it was anything to do with her. We analysed the situation for a while, before concluding that it was simply an extreme COVID-influenced version of Norwegian’s general uncomfortableness. (In our opinion, being uncomfortable is the norm for Norwegians.) This made us laugh, since in normal times, exhibition openings are often quite awkward, but in this self-isolating time, they become even more so.

Eggen’s work is concerned with the body and its involuntary actions, the ones we deem irrational. As she once explained in an interview with me, these actions are on a par with affect theory: they turn us away from the rational and towards the notion that something more basic informs our actions, such as muscles, reflexes and instinct. For this new work, she had made three frameless photographs on polytex paper of hands twisted into each other, hung directly on the wall. As she says about the work, this is an attempt at advancement within an anatomical form. Both hands in each image belongs to the same person, but act as if they are from two different persons, with one holding the other back.

The title, Tranquilshiver, along with the unease they convey, reflecting the way we feel at this point in time, made me smile. A tranquil shiver: does that even exist?

CLAIM YOUR SUPERIOR BONE. Admir Batlak & Ingrid Eggen. 21.11.20 – 20.12.20.

ANDREA GRUNDT JOHNS

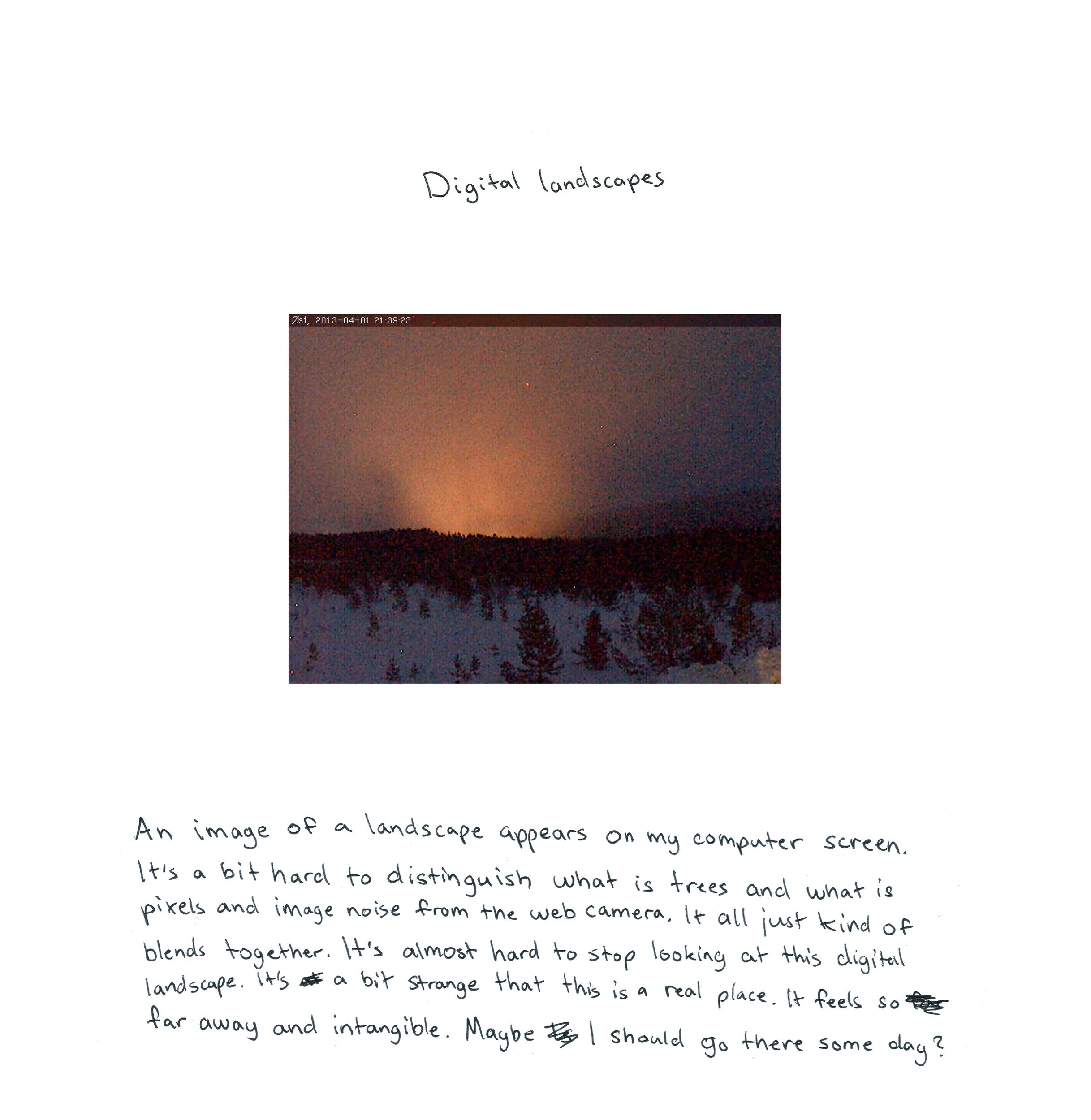

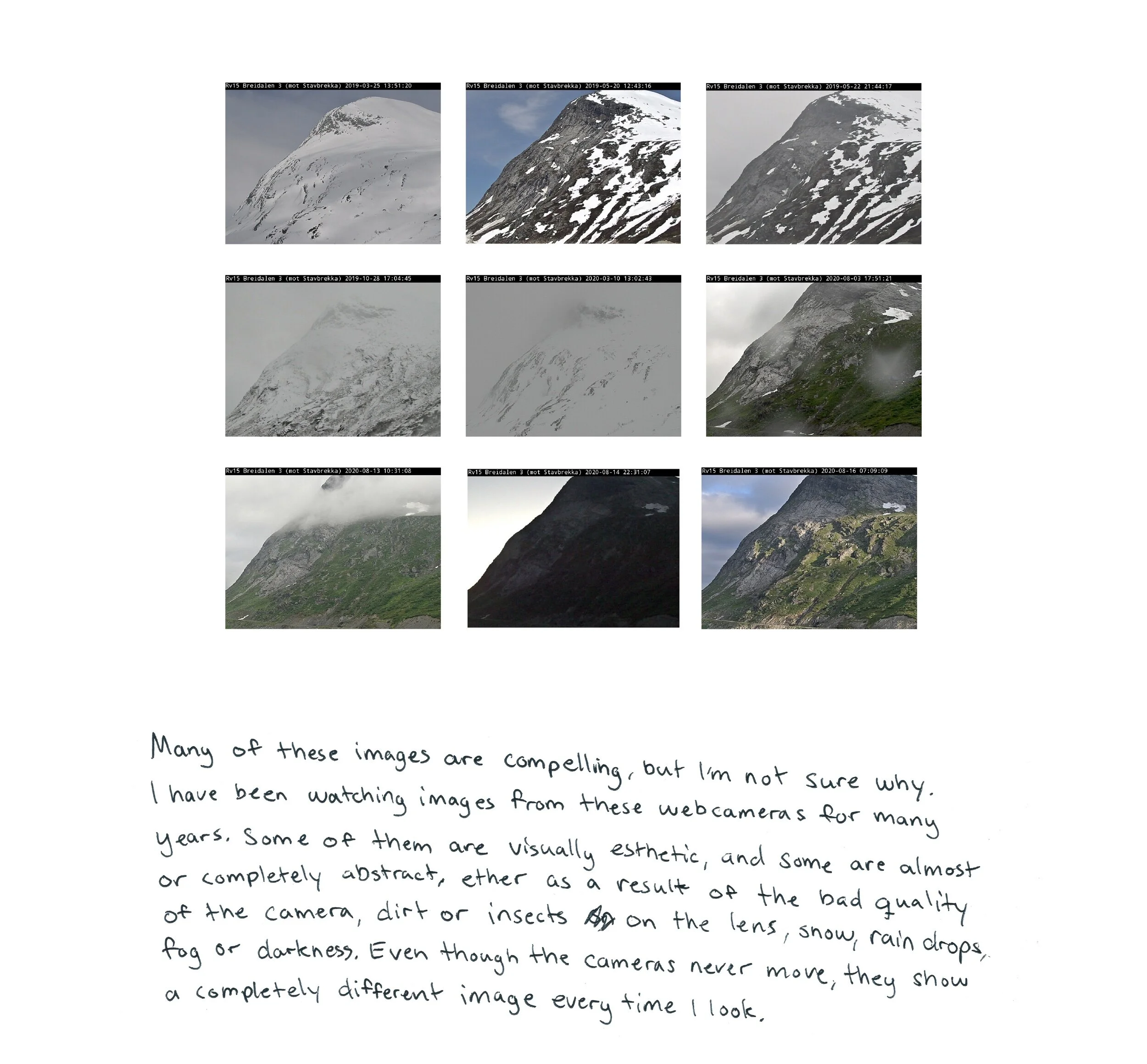

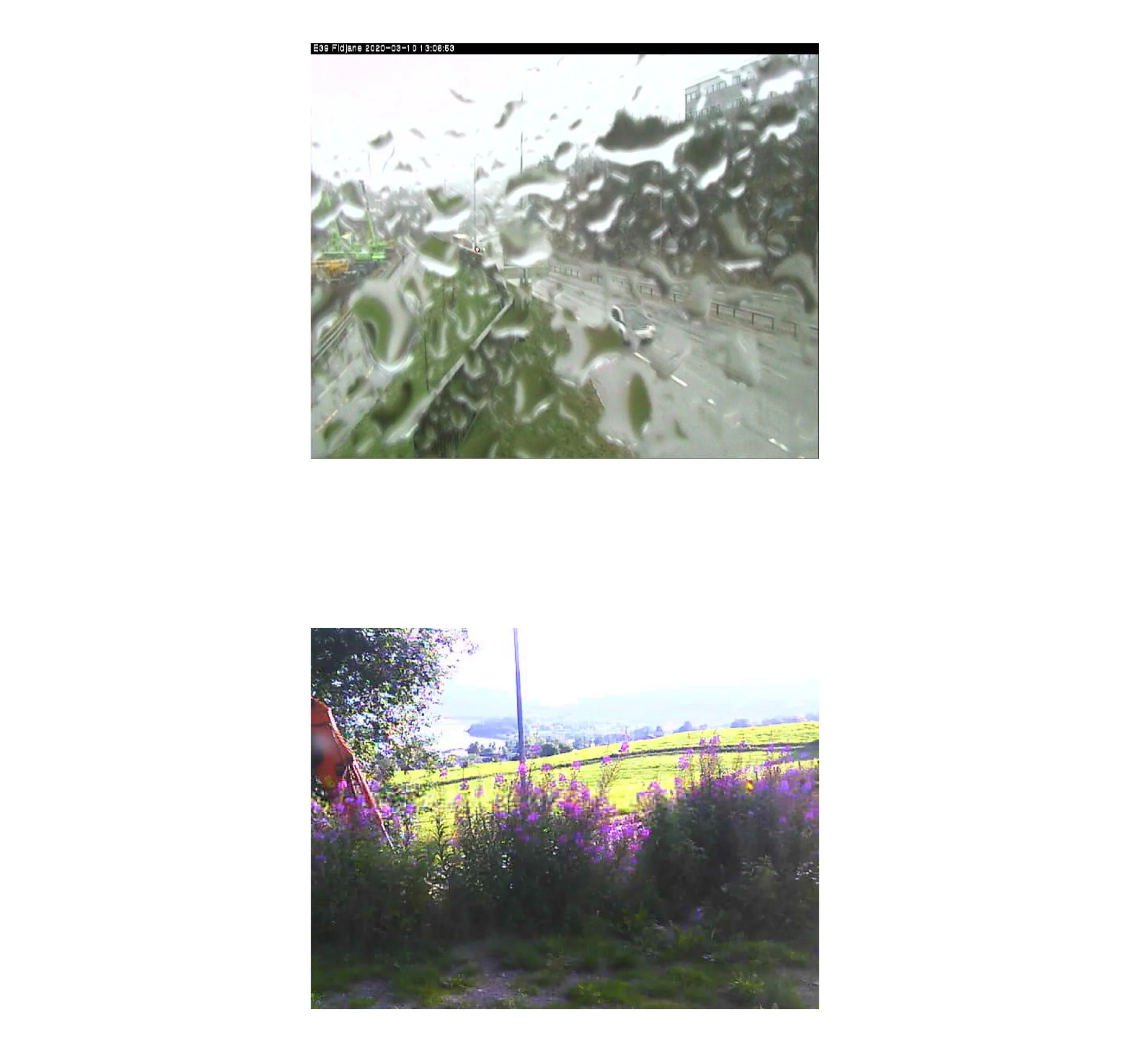

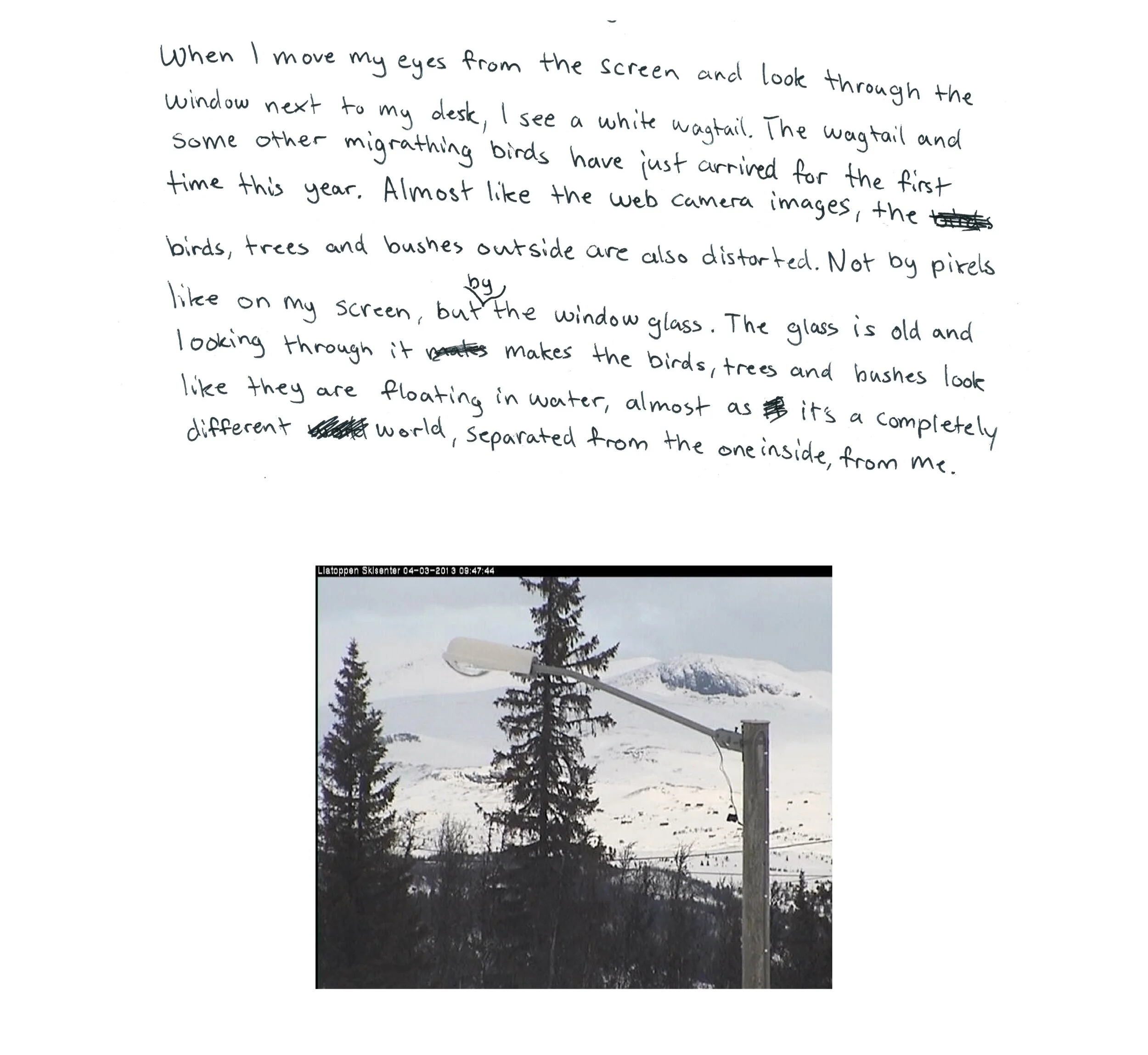

This text contains translated extracts from my master thesis written in March 2020. It is based on many years of research on photography, sight and perception. Have we lost the ability to see due to the enormous amount of visual material filling our daily lives? Are we being blinded by too much information? How can we, if need be, learn to see again? And what does seeing actually mean?

The original text was finished at the same time as large parts of the world were suddenly shut down, moved over to digital space, and thinking about touch became a pressing matter.

Le visible et l'invisible

I have walked 7,244,629 steps since I moved to Bergen 775 days ago. That is, approximately 9,348 steps per day. On a normal day, when I walk to the studio and back, I walk around 6,500 steps. Many governments now recommend an average of 10,000 steps per day. Several days this spring, my step count is down to only a few hundred steps a day.

___

There is an imbalance in our sensory system.

Vision separates us from the world, whereas the other senses unite us with it.

___

There are mirrors on the Moon to measure the distance between us and it. The mirrors were placed there during the voyages of Apollo 11, 14 and 15.

Light hits a surface, and a reflection is created. The surface's microscopic topography dictates all reflections. The surface catches the light and throws it back at us – either as the near perfect reflection in a mirror, or as the soft light on our living-room wall when the afternoon sun hits its rough surface. The smoother the microscopic topography, the more lifelike the reflection.

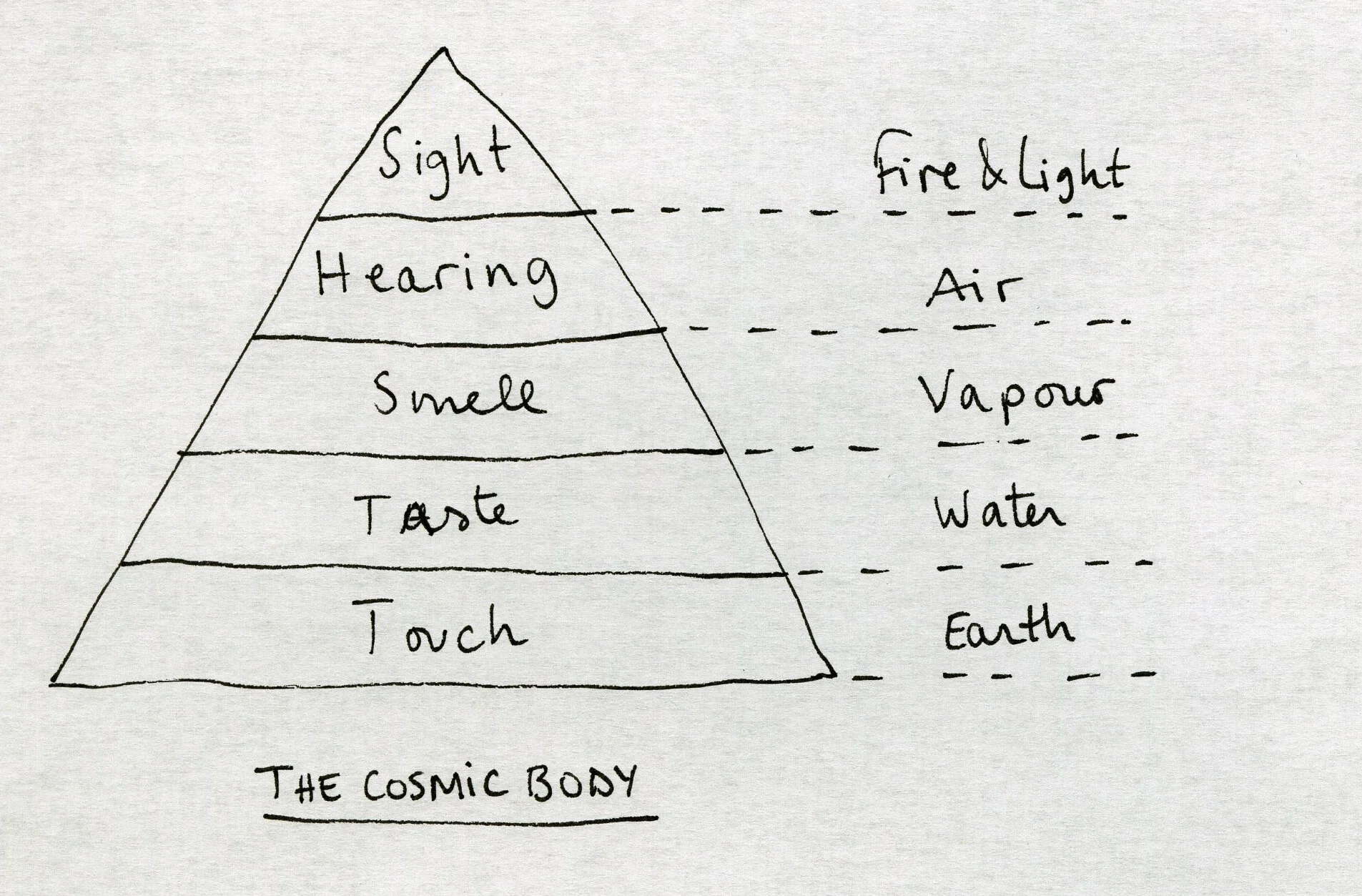

According to art historian Hans Belting, the ancient Greeks never really managed to decide if what they saw in the mirror was reality or trickery. This confusion is partly explained through their understanding of sight. Through the Emission Theory, Plato explains that we see because of light emitted from our eyes, that we see the objects in front of us only when the light from our eyes hits the object. The ancient Greeks’ idea of the Cosmic Body placed sight at the top of the sense hierarchy. Sight is light is fire is enlightenment. At the bottom is touch, and earth. Touch, treacherous, dangerous, confusing and seducing. Thus sight became the most important sense in the western world.

According to the Arab scientist Ibn Al-Haytham and his studies on optics from around 1,000 ad, there is an important difference between visibility, an optic phenomenon, and visuality, a psychological phenomenon. It is only through prefrontal mental synthesis that we are able to see, that we are able to understand and translate the light that hits our eyes. Memory and contemplation become essential in the process of seeing. Thus only details are needed to be able to understand the larger picture. We see because we have already seen.

A reflection is created when reflected upon.

Some months ago, I talked to a friend of mine who is currently working on developing eyes for robots. Their goal is to make robots that can see and recognise what is placed in front of them. A step closer to replacing humans with machines. The idea is fairly simple. The robot will get two ‘eyes’ – one working as a projector, emitting light, hitting the surfaces in front of it, the other as a camera recording and registering the shape of the object in front of it and the distance to it. They have already made great progress in their research.

___

We look, register and name. John Cage once said that we stop seeing when we start to name and categorise. ‘You look at a conifer [for instance] … and because it all looks basically alike [like other trees], you say it's a tree – and when you say that you cease to look. But only if you move from understanding to actual experience can you really begin to see.’ Seeing can lead to blindness.

___

There is something about being allowed to touch.

Last July in Japan I removed my shoes whenever I entered a space. Off with the shoes, on with slippers, or socks or barefoot. I feel an over thousand years old dark and smoothly polished wooden floor under my feet. It is burning hot in the sun, cooling, soothing in the shadows. After a long day in hard, dusty sandals, I step into the softest whitest plushest slippers and into a stark white art installation. Suddenly, I am inside the wooden floor, inside the installation. Suddenly I feel my surroundings. After a month of taking off my shoes I start to notice a certain change in perception, a certain change in the way I experience my surroundings. I have started to see with my feet. It occurs to me how much information I lose by wearing shoes. What if we wore gloves on our hands all the time?

Seeing with other senses can make us see again.

After thousands of thumbs being stuck into a hole in a column in Hagia Sofia in Istanbul and then twisted around 360 degrees for hundreds of years, the sweating-column, weeping-column, or wishing-column now has a clear scar on its side. The hole is as deep as a middle-sized thumb, and its contours are golden from the stroke of hands.

In a park in Oslo, the tightly clasped fist of a young bronze boy has become golden from the repeated touches from visitors. In the museum next door, the visually impaired could up until recently touch a few selected sculptures with signs in Braille.

At the Kiasma museum in Helsinki, all visitors are invited to press their hands against a cold, now dirty and greasy, marble plate at the entrance. Slowly we create a concave surface. Some time after my last visit to Kiasma, I read by chance in the foreword of The Eyes of the Skin by Juhani Pallasmaa, that the museum's name is a Finnish version of ‘chiasm’, a word the architect found in a chapter in Merleau-Ponty's Le Visible et l'invisible. The visible and the invisible.

There is something about being allowed to feel.

Some time before I move to Bergen I decide that I will walk wherever I go. Walking becomes my sole mode of transportation. I walk everywhere.

___

Our skin is our largest organ. Covering everything, making us feel with our whole body, the skin covers our tongue, our ears, our eyes. Touch is both external and internal. Touch is when we feel the humidity or the heat outside. Touch is when we feel pain or pleasure inside our bodies. Touch is when different body parts relate to each other without us thinking about it. Touch is the movement of our body. Touch is the only sense we cannot loose.

Lately, the word ‘haptic’ has emerged when talking about our sense of touch. The haptic refers to a combination of sight and touch, allowing us to understand and feel texture without touching. But to do this we have to touch first, to create a library of haptic memories.

Once, I experienced the lack of touch over a longer period. I had just moved away from home for the first time, and had almost no physical contact with others for half a year. It felt as if my body was imploding. Silently, slowly, sucking, sinking into itself. I was amazed and baffled. I remembered the horror stories from my childhood about orphanages where children grew up with serious disorders due to the lack of touch.

___

We break the surface. We see with our hands and feel with our eyes. They lead our fingers quickly over the touch-screens. We cannot feel our way anymore. How do you feel an app?

CLAUDE CAHUN

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This is the last week of Fantastic Women – Surreal World at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, where the work of Claude Cahun, among 34 others, is displayed. Cahun was a pioneer of photography that worked with gender fluidity and identity, and in this sense we owe her a lot. In one self portrait, Cahun is dressed as a weight lifter with the text: ‘I am in training, don’t kiss me’ on her jersey, and a small heart on each cheek, as well as one drawn on her knee. Her quote on gender accompanies the work: ‘Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation.’

It’s almost too much of a coincidence that this show is on at this time in this small Scandinavian country, since it’s been an interesting fall for Denmark. Three years after the MeToo Movement swept over at least the western part of the world, Denmark has finally begun its own investigation into people in powerful positions. A quote by the famed writer Suzanne Brøgger is circulating on social media. She said to the Danish newspaper Børsen that she has no patience with people who complain about MeToo. She doesn’t listen to those inexperienced people who say that women are to blame for their own abuse because they could just say no thank you, dress differently or simply stop putting themselves in dangerous situations. She is at an age where she trusts her own experience, and yet the politician Pia Kjærsgaard is only two years younger, but is one of those who have opposed the movement in Denmark, saying that women must accept advances, and diminishing harassment to simple, innocent flirting. Kjærsgaard claims never to have experienced unwanted attention or sexual advances, and yet she doesn’t hesitate to dictate what other women should put up with. Has she really never been touched by a man without her permission? Luckily, this time she’s outnumbered by many famous men and women, who are standing together, keeping up the momentum of the movement. It all began when the 30-year old TV host Sofie Linde delivered a powerful opening monologue at the TV Zulu Awards, watched by mainly young people, which was the perfect audience to finally hear someone say that enough is enough.

The movement spread quickly from the media world to the art world, giving this exhibition at Louisiana extra importance. If you didn’t catch it, there’s consolation in the fact that this week the great retrospective of the work of Anna Ancher opened at the National Gallery in Denmark. Not a moment too soon.

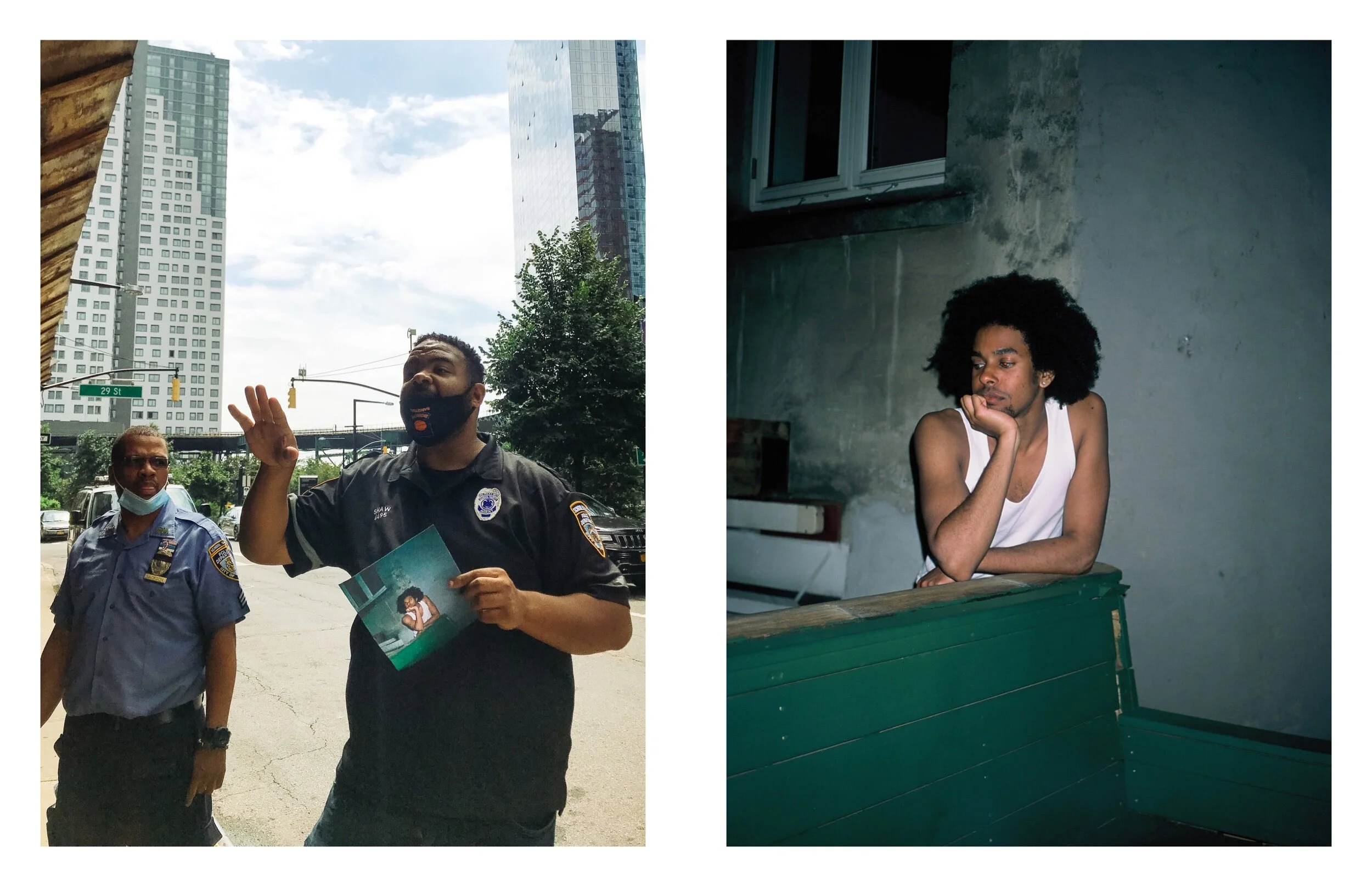

PROTESTIMAGE

Found via Feminist News on Facebook. Photographer unknown.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There’s an image from the recent protests in Poland that I can’t stop thinking about. A woman stands in the middle of a street, in the midst of a demo, wearing a mask and waving a Pride flag in all the smoke and chaos. She seems angry, which is understandable and relatable. Why shouldn’t Polish women be able to decide what happens in their own wombs? It’s 2020 and I can’t believe that we’re here again, with the election of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court putting the American right to abortion in danger, and so the image from Poland hits me. I’m with her in this protest. I’m with her on the issue of choice. It’s vital to me that every single woman gets to decide what to do with her own body. And it’s terrifying how this choice is still being threatened. It reminds me of the image that went viral some years ago, from another protest, of a woman in her sixties holding the sign: ‘I Can't Believe I Still Have To Protest This Fucking Shit.’ She’d obviously done this before. We know that we, and our daughters, stand on the shoulders of our mothers, their grandmothers, who fought for the right to choose. And yet here we are again.

In 2017, I co-curated an exhibition called Subjektiv at Malmö Konsthall showing the work of Josephine Pryde among others, whose series It’s Not My Body shows MRI scans of a foetus in the womb montaged onto colour landscape shots. Pryde hadn’t been intending to take part in any ‘urgent response’-type exhibitions at that specific political juncture, but what caught her attention was another chance to NOT say how it feels to be a pregnant individual. She was interested in describing a shared material state, and included these pieces in the exhibition because she thinks human reproduction is extraordinary and that the history of women as property, as the designated site of reproduction, still haunts our popular mythologies and cultural exchanges. How these ghosts return, how they duplicate themselves and occupy imaginations, is a matter of intense relevance to her, and also to us four years later in these very trying times. So all these thoughts and feelings arise in my mind when looking at the Polish woman waving her flag in Warsaw. I do hope that we won’t have to see images like this in the years to come.

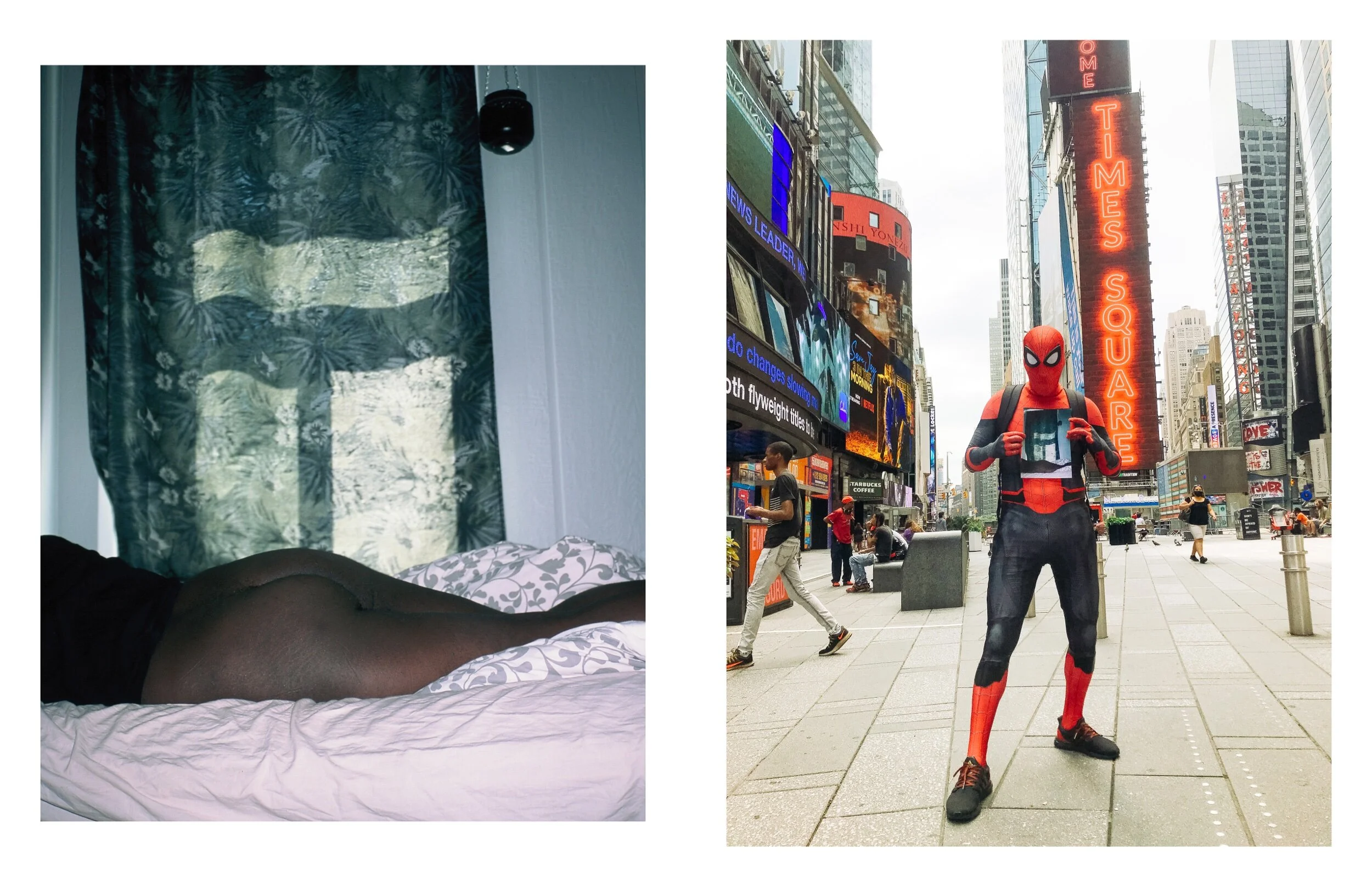

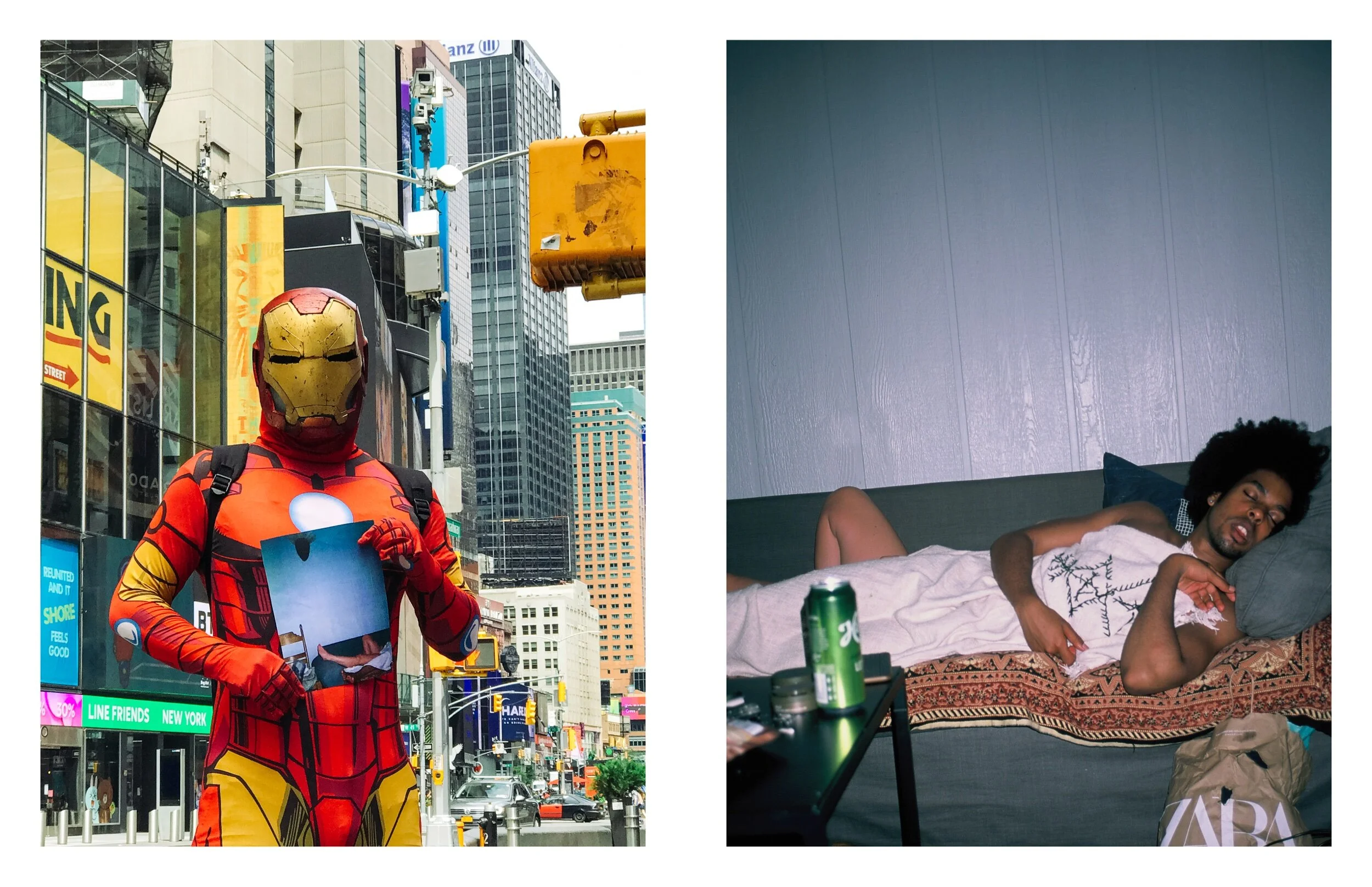

SOFIE AMALIE KLOUGART

Immediate Vicinity

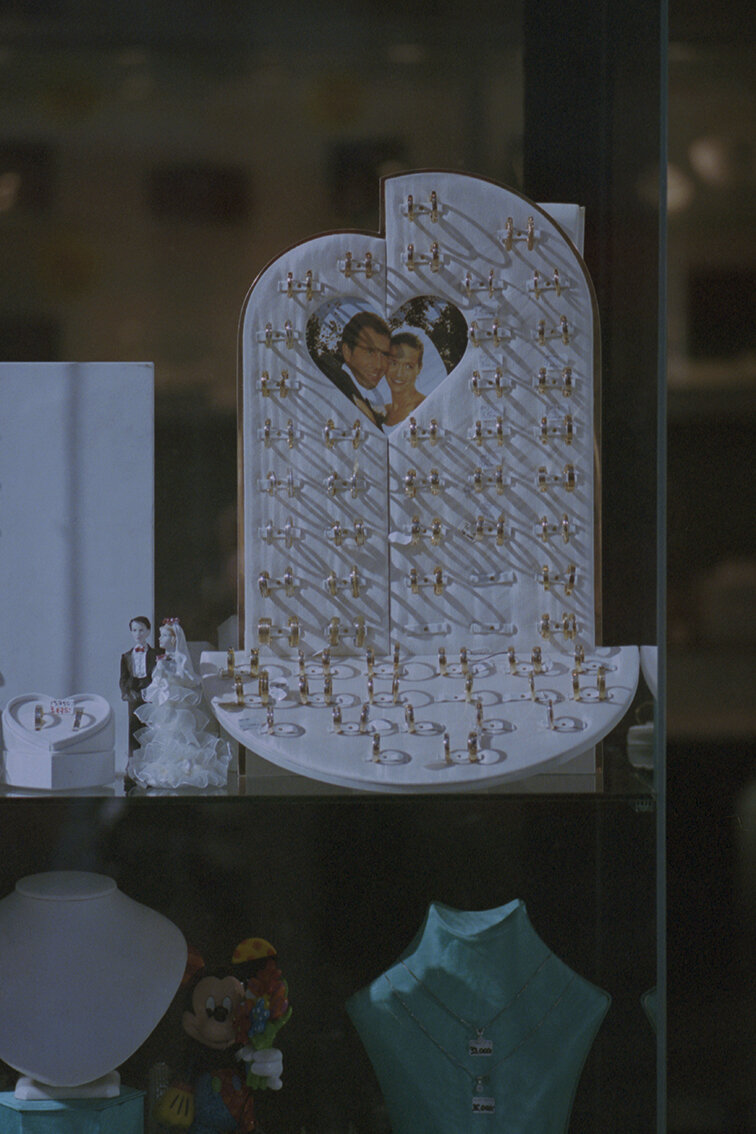

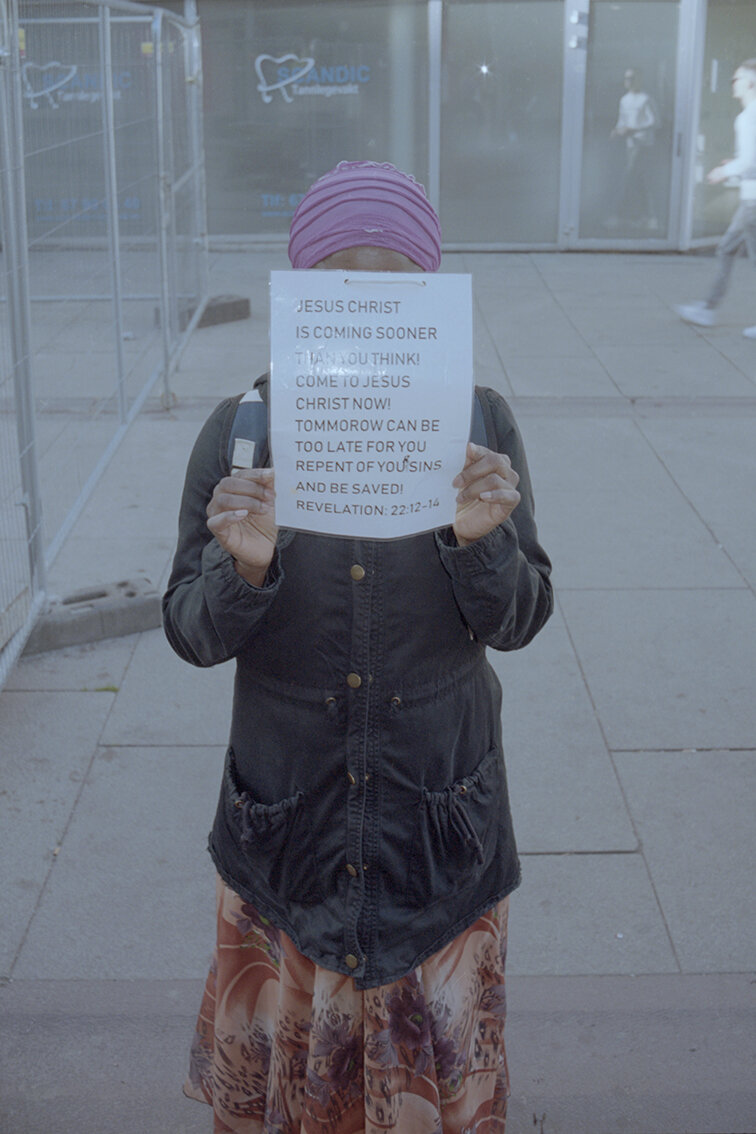

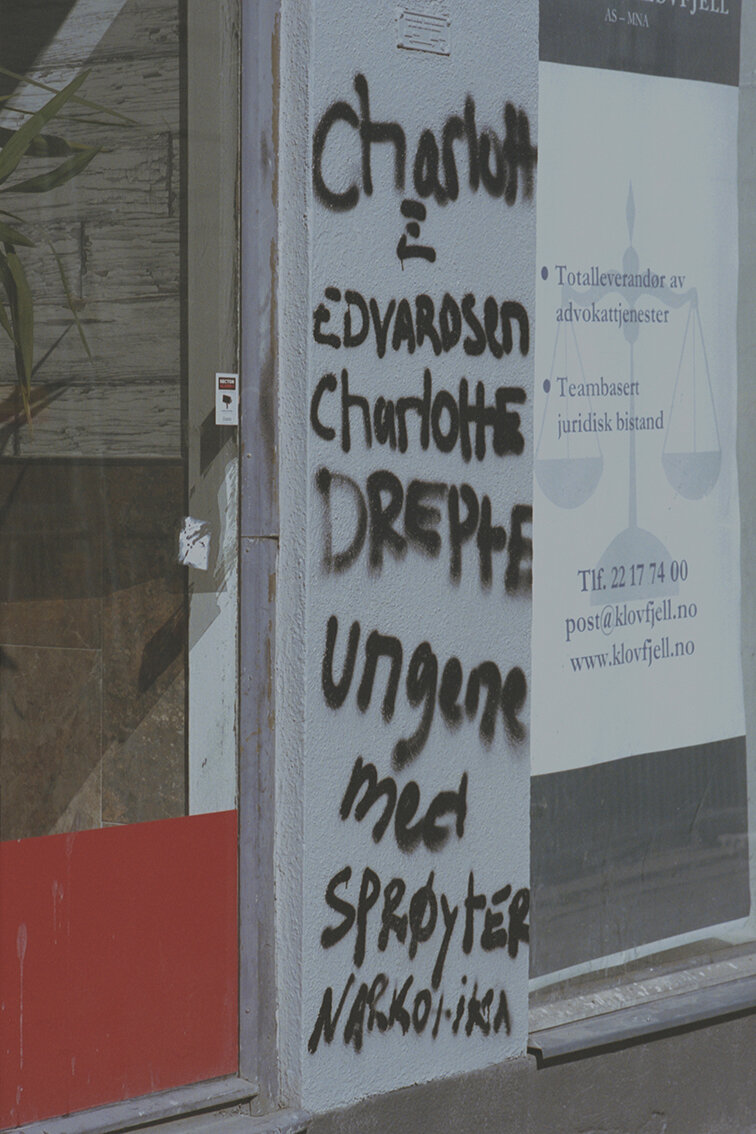

Here in Storgata, Oslo, we either have to stand close to each other or shout to be able to communicate. Storgata is being upgraded, according to the website of Oslo Municipality, and in the early hours of the day the noise from the construction work is constant. They’re building wider sidewalks, new tram tracks, more tram stops, a new water and sewer network. I don’t recognise Storgata on the architects' renderings of a future street. In the drawings, Storgata is an avenue with blossoming cherry trees and people on the move. No one is begging or injecting heroin. No large groups of misfits in front of the Gunerius shopping centre, no police, guards or social workers. Here, everything is neat and tidy.

For two years I’ve lived in Norway, and for just as long I’ve wanted to photograph the area where I live. I’m documenting my immediate vicinity and some of the people who characterise this urban space before it disappears for good.

CHRIS KILLIP

Simon Being Taken out to Sea for the First Time since His Father Drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, negative 1983; print 2014, Chris Killip, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of and © Chris Killip. Image from the exhibition Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante, May 23-August 13, 2017, Getty Center.

Afterimage by Matthieu Nicol:

What image do I have in mind at the moment? It’s difficult to give a quick answer to the question Objektiv has proposed. In my work as a photo editor for the daily press, I see thousands of shots on my monitors every day. This ocean of images, mainly from agencies, formatted, and in the end, very similar, does not help with digestion. Rather than writing about press photos, I want to talk about images or series of images from exhibitions or festivals that has made an impression on me lately. But when squeezing, nothing came out. So I put this question in the corner of my mind for a few weeks, and let it decant. Regularly, like the backwash of a wave, a handful of shots came back; sometimes engulfed but eventually graved in my visual memory. Nothing new, nothing current. So I allowed myself to slightly modify the question: which image, absorbed a long time ago, has stayed etched in my memory and resurfaced regularly?

Among the icons of my “imaginary museum”, there is one that haunts me. A terrible image of infinite sadness but of absolute relevance. In Madrid, February in 2014, an exhibition soberly entitled Work, a retrospective of the work by Chris Killip, was presented at the Reina Sofia Museum. I knew the photographer’s work, and several of his series on the impoverished communities in northern England, the victims of deindustrialization in the early 1980’s in the beginning of Thatcherism. I’d seen them online or in catalogues, notably In Flagrante (1988). But this image was unknown to me because it was absent from the books.

I don’t want to linger on the formal composition of the scene, the position of the body and the closed eyes of the little boy in his Sunday best, floating in adult clothes, his head bent on the line of the horizon, the slight oscillation of a swaying boat, of which only the bow is in the frame. A form of a closed room, without doors or windows, perfectly executed. I would, however, like to emphasise the caption: Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Everything we need to know is there, in this exact wording. A subject, described by his first name, the reason for his presence, a place, a date. 18 words.

Although the image alone can produce this piercing effect, this “punctum” dear to Barthes, allowing the observer to appropriate it beyond all knowledge, code or culture; the caption gives us information that is essential to our comprehension. What is mind-blowing in this link between text and image is that it reveals the evidence of an extraordinary situation. It enables an immediate comprehension of the degree of commitment the photographer has with his subject. Killip’s approach is unique, the author is distant, out of frame and at the same time, completely immersed in a poignant intimacy. Only the construction of a long- term relationship with this tiny fishing village named Skinningrove, where he documents the daily life of its inhabitants, allows him to produce a scene like this and show it to the world.

With an image so prone to allegory, one could make it say a number of things: a rite of passage into adulthood, filial love, sadness and sorrow. One could also enter into dialogue with other images, I’m especially thinking of the one of Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach in September 2015. This “shock image” that rapidly went worldwide, became the tragic symbol of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean. In this reversed perspective we see a small, drowned body and not the survivor, his father, who subsequently testifies of the drowning to international media. Within me, the connection is evident: in my visual memory, these images are contemporary, and as a father of two children the age of Simon and Alan, they move me particularly. But the comparison stops there. We cannot suspect Killip of voyeurism. His restraint, his sense of propriety, his engagement, his empathy are all entirely resumed in this image and its caption.

During a presentation at Harvard University in 2013, where he taught from 1991 to 2017, Killip confides his discomfort on the use of this scene and a few other images taken that day: “I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... ». And indeed, the author dismissed the image from the two editions of In Flagrante (1988 and 2015). During a later conversation held in 2017 at the Getty center in Los Angeles, he clarifies: “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act’, and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

En français:

Quelle image ai-je en tête en ce moment ? Il m'a été compliqué de répondre rapidement à cette question, à l’invitation d’ Objektiv. Dans mon travail d'éditeur photo pour la presse quotidienne, je vois passer plusieurs milliers de clichés par jour sur mes moniteurs. Cet océan d'images, principalement d'agence, formatées et finalement fort similaires n'aide pas à la digestion. Plutôt que de photos de presse, j’ai alors cherché à parler d'images ou de séries m’ayant marquées dernièrement dans des expositions ou des festivals. Mais en pressant, rien ne sort. Et j'ai mis cette question dans un coin de ma tête durant quelques semaines, et laissé décanter. Régulièrement, tel le ressac, reviennent une poignée de clichés parfois engloutis mais finalement gravés durablement dans ma mémoire visuelle. Rien de neuf, rien d'actuel. Alors je me suis permis de modifier quelque peu la question : quelle image, assimilée depuis longtemps, est restée gravée dans ma mémoire et refait surface régulièrement ?

Parmi ces icônes de mon « musée imaginaire » il y en a une qui me hante. Une image terrible, d'une tristesse infinie, mais d’une justesse absolue. C'était en février 2014, à Madrid. Une exposition sobrement intitulée Work, rétrospective du travail de Chris Killip présenté au Musée Reina Sofia. Je connaissais le travail du photographe, et plusieurs de ses séries sur les communautés paupérisées du nord de l’Angleterre, victimes de la désindustrialisation à l’aube des années 1980, début du Thatcherisme. Je les avais vues en ligne ou dans des catalogues, et notamment In Flagrante (1988). Mais cette image m’était inconnue, car absente de ces ouvrages.

Je ne souhaite pas m’attarder ici sur la composition formelle de cette scène, la position du corps et les yeux fermés de ce petit garçon endimanché, flottant dans des habits d’adulte, sa tête courbée crevant la ligne d’horizon, la légère oscillation d’une barque qui tangue et dont seule la proue est dans le cadre. Une forme de huis-clos, sans portes ni fenêtres, parfaitement exécuté. Je voudrais en revanche insister sur sa légende : Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Tout ce que l’on a besoin de savoir y est dit, dosé au mot près. Un sujet, décrit par son prénom, la raison de sa présence, un lieu, une date. 18 mots.

Si l’image seule peut créer cette fulgurance, ce « punctum » cher à Barthes qui permet à celui qui l’observe de se l’approprier, au-delà de tout savoir, de tout code, de toute culture, la légende ici donne une information essentielle à sa compréhension. Ce qui est sidérant dans ce rapport texte-image, c’est qu’il révèle l’évidence d’une situation exceptionnelle. Il permet de comprendre immédiatement le degré d'engagement du photographe avec son sujet. La pratique de Killip est singulière, l’auteur est distant, hors cadre et en même temps, totalement immergé dans une intimité poignante. Seule la construction d’une relation de long terme dans ce village de pêcheurs nommé Skinningrove dont il documente au long cours la vie quotidienne des habitants, lui permet de produire une telle scène et de la donner à voir au monde.

On pourrait faire dire beaucoup de choses à cette image qui se prête facilement à l’allégorie : celle d’un rite du passage à l’âge adulte, de l’amour filial, de la tristesse et du deuil. On pourrait également la faire dialoguer avec d’autres. Je pense en particulier à celle d’Alan Kurdi, ce garçonnet syrien échoué sur une plage turque en septembre 2015. Cette "image-choc", qui a rapidement fait le tour du monde, est devenue le symbole tragique de la crise des migrants en Méditerranée. Dans un retournement de perspective c’est ici un corps de petit noyé, mort, que l’on voit, et non le survivant, son père, rescapé, qui témoigne après-coup de la noyade auprès des médias internationaux. En moi, le lien est évident : dans ma mémoire visuelle, ces images sont contemporaines, et en tant que père de deux enfants de l'âge de Simon et d'Alan, elles m'émeuvent particulièrement. Mais la comparaison s'arrête là. On ne peut pas soupçonner Killip de voyeurisme. Sa retenue, sa pudeur, son engagement, son empathie sont tout entiers résumés dans cette image et sa légende.

Lors d’une présentation à l'Université Harvard en 2013, ou il a enseigné de 1991 à 2017, Killip confie sa gêne sur l'usage qu'il pourrait faire de cette scène et des quelques autres images réalisées ce jour : « I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... » Et de fait, l’auteur a écarté cette image de ses deux éditions d'In Flagrante (1988 et 2015). Lors d'une conversation plus tardive, tenue en 2017 au Getty Center de Los Angeles, il précise : “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act,’ and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

This text is translated by Anja Grøner Krogstad.

ÅSNE ELDØY

Exercises in Structure, part 2.

Concrete fragment A, satellite series, I-III (2020). Concrete fragment B, inside series, I-III (2020). Quarry no. 06, no. 23 & no. 24. (2019).

Time is now longer than other times. It moves slower than it used to. It’s a time for practice. Recurrence. Repetition.

ANTHEA BEHM

I started making photographs when I was in high school through an after school darkroom class. It was a volatile time in my life, and the darkroom provided a space of refuge.

My high school darkroom, like many community darkrooms, had a series of enlargers in a row that were separated by dividers. Working in the dark at one of these stations gave me much needed space where I could pause and take cover. As in many such darkrooms, the trays of chemicals where you process your prints were shared. When it was time to put my paper through the chemistry, I moved from a singular, solitary position into a communal one. This was a space of gathering, and also of care: when moving your prints through the trays, you needed to be aware of affecting other prints that were also mid-process.

This separation of space was not absolute. Even when you’re alone at your enlarging station, you must be mindful of your community. For example, you must ensure that you don’t turn on your enlarger with the negative carrier open, which could mistakenly expose your neighbor’s paper to light. And even though—like much human activity—analogue photography can be destructive to the environment, the rules of the darkroom help minimize harm; for example, never pouring fixer down the sink.

Today, I am processing prints in my studio darkroom in Gainesville, Florida, where I am also sheltering in place. I work alone, but within this distancing there is also connection and care. Our experiences and our relationships—to ourselves, each other, and the world—are not fixed in a final photograph. They are the entire process.

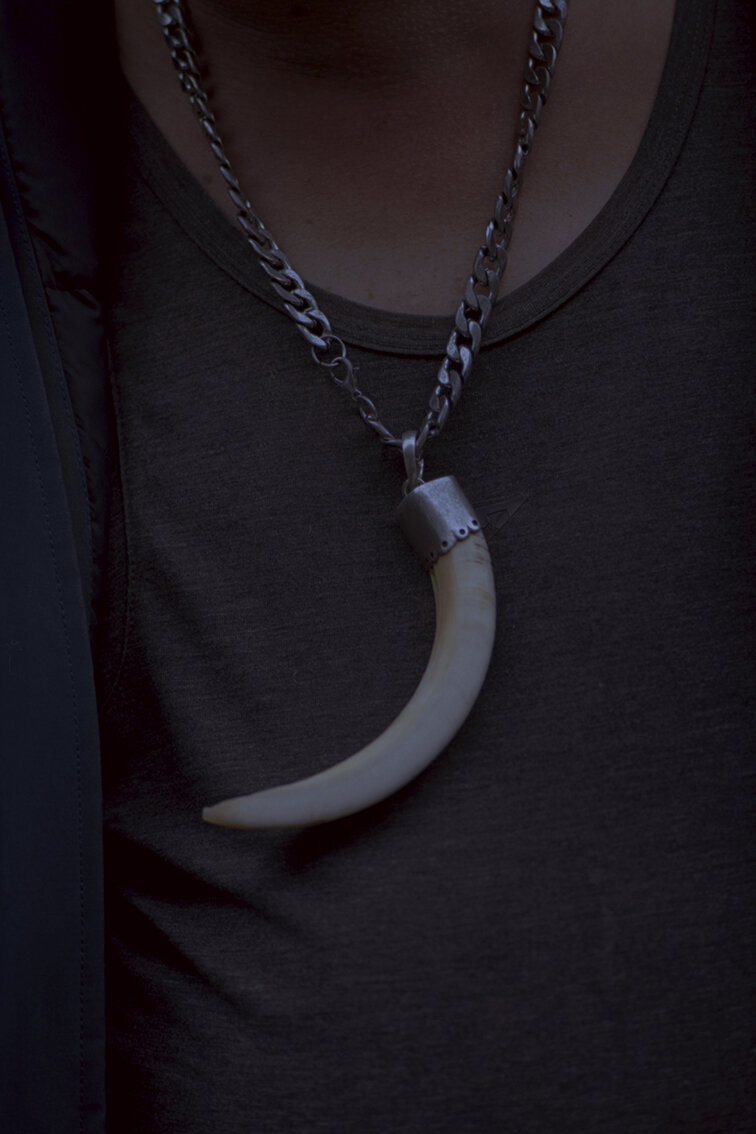

MELANIE KITTI

I found so many claws

Rip rip

Found them on the lawn where they

put rips in a pair of sneakers from below

Drank milk from various udders

and I paid a witch to do it

I paid to watch her drink

She left the udders dripping

ripped her cheeks with one of the claws

I filled her third eye

I whipped a pigeon on the breast

It was about to put its jaw around

a potato on the table edge

Frayed at the edge

Teeth gnashed

I made the pigeon feel shame

Then I caressed the pigeon’s wing tips

with my finger tips

was fluent in words that

counted backwards, three

I caressed the wing tips back and forth and

I put pressure on the vein’s end

I dropped all of my peas in the background

Turned around

I turned my peas around the wrong way

Picked too many peas to bead on the thread

and I spent time in the fog

I spent time with the pigeon and the fog froze

I kept a very tight grip on the thread end

I collected the fog and I weighed it

Lost my grip

Ran between my fingers and my head shrunk

Mash all over

I whipped the pigeon once again

The pigeon’s jaw popped

JEET SENGUPTA

As the situation around the world gets worse every day with the news of the rise in deaths, I’ve become paranoid about losing my parents. Even though we’re living together, I cannot get this fear out of my head. A number of times, I’ve imagined that they are dead.

In the early stages of lockdown, I used to check my parents’ temperatures every other day. The seriousness of the disease and its ability to spread within the community has made me doubtful of the people on the streets, even neighbours and friends. Every morning, half awake, I call out to my mother from my room to get her response, to know she’s still there. When I hear her voice, I go back to sleep again. Somehow this makes me feel safe, even in my dreams. But I’m scared that one day, I’ll hear only silence.

It’s been over two months now. The fear of the pandemic has now also become fear of people. I am worried that I will isolate myself from the world even after the lockdown ends.

DAVID GEORGE

16th APRIL 2020.

AS A LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHER MY PRACTICE HAS BEEN COMPLETELY CURTAILED BY LOCKDOWN SO I HAVE TAKEN TO RECORDING MY DAILY 5AM DOG WALKS AROUND HACKNEY, LONDON ON AN OLD IPHONE 5 .

SARAH MEADOWS

I'm thinking about spring, all of the spring happening that I can't experience. Fertility, growth, and life cycles are cycling onward outside of my house and I wish I could be out there.

Frog and salamander egg images from google searching in my room. May 13, 2020.