EMILE RUBINO

Today, photography continues to occupy an ambiguous position between art and non-art. But I would argue that this indeterminate position is actually one of photography’s greatest strengths because it holds a subversive political and artistic potential. As an outward-looking medium, photography is also inevitably derivative as it always seeks to mimic, copy or emulate aspects of other mediums such as painting—just as much as it mimics and copies ‘the real.’ For better or worse, photography’s equivocal position as art (but also its inferiority complex) is still the engine that keeps the medium moving: both forward and backward… So illustration (or illustrating illustration so to speak) struck me as a relatively unassuming way to think about much bigger questions pertaining to the contentious history of photography’s political potential.

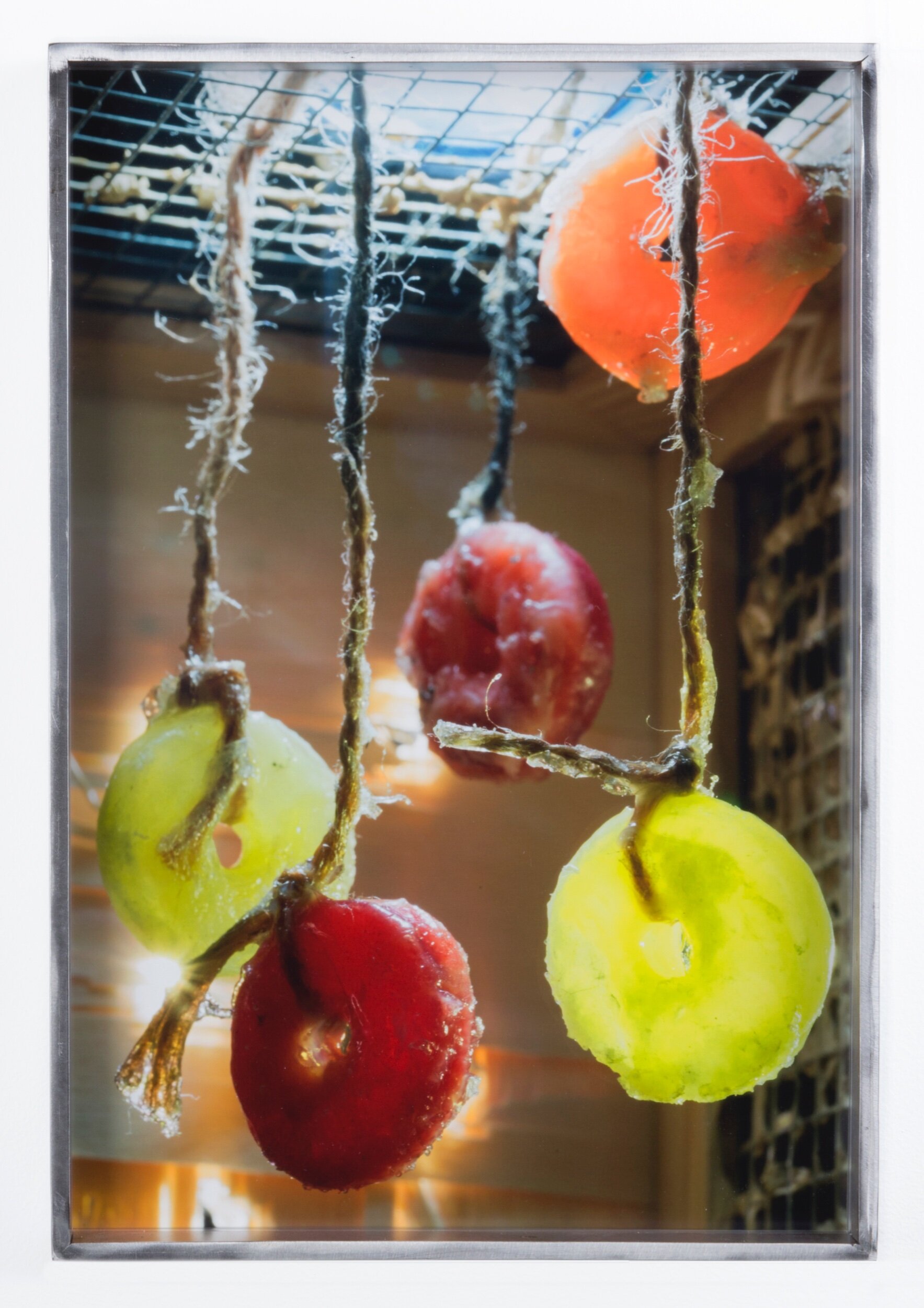

Emile Rubino, Illustration, 2024. Photo credit: Useful Art Services. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda

EMILE RUBINO in conversation with Lucas Blalock.

Lucas Blalock: Your show of recent photographs at LambdaLamdaLambda was called Illustration. This strikes me as a funny quality of photography to foreground in an exhibition, an idea reiterated in the exhibition text written by Aaron Peck. Can you talk a little about where this is coming from?

Emile Rubino: Photography is always tasked with illustrating. It was very productive for me to recognize that it’s actually rather bad at it. To some extent, a photograph is always ambiguous and even when photography attempts to forgo its inevitable ambiguities, it often ends up creating new ones that are potentially even more confounding. I find this shortcoming of photography to be fascinating because depending on how you handle it, you can make a picture do very different things through minor gestures. So I began to use the notion of illustration as a lens or a prism through which I could consider photography. For instance, I started noticing different kinds of pictures where objects were stacked on top of one another or placed side by side in the most literal way, like simple mathematical equations (i.e Euro bills + heater = energy precarity, or again, white eggs + brown egg = discrimination)… Photography has a long and strange history related to equations as a way to make sense of things that can't be rationalized. To explain the modernist concept of Equivalency, a photographer like Minor White also used an equation, which went like: ‘Photograph + Person Looking ↔ Mental Image.’

Illustration came as a way of giving myself license to overthink these seemingly simple equations by foregrounding photography’s brilliant dumbness. But I also came to focus my attention on illustration by thinking about the way in which it perfectly encapsulates photography’s forever ambiguous position between art and non-art. Both photography and illustration can be considered to be petit métiers, and their histories are materially intertwined. On a commercial level photography posed a threat to illustrators (more than painters) in the 19th century, which is partly why many of the first commercial photography studios were opened by illustrators and caricaturists like Nadar.

I’ve always been fascinated by the work of the great illustrator and caricaturist Honoré Daumier who was very much in the back of my mind in the making of this exhibition; especially his famous caricature of Nadar in his air balloon with the witty caption: ‘Nadar elevating photography to the heights of art.’ In the realm of art, to say that something is ‘merely illustrative’ is a commonly accepted form of criticism; it is as common as saying that a work is ‘derivative.’ So here I am embracing and celebrating both the illustrative and also the derivative nature of photography. But other artists do that too in very different ways. I recently learned that Torbjørn Rødland used to be an editorial cartoonist, which makes so much sense. His best pictures work like cartoonish jokes and illustrations pushed to an extreme.

Today, photography continues to occupy an ambiguous position between art and non-art. But I would argue that this indeterminate position is actually one of photography’s greatest strengths because it holds a subversive political and artistic potential. As an outward-looking medium, photography is also inevitably derivative as it always seeks to mimic, copy or emulate aspects of other mediums such as painting—just as much as it mimics and copies ‘the real.’ For better or worse, photography’s equivocal position as art (but also its inferiority complex) is still the engine that keeps the medium moving: both forward and backward… So illustration (or illustrating illustration so to speak) struck me as a relatively unassuming way to think about much bigger questions pertaining to the contentious history of photography’s political potential.

Emile Rubino, Samozveri, 2024. Photo credit: Useful Art Services. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda

To ground this discussion a little more, I would say that the starting point in the studio was Alexander Rodchenko’s series of photo-illustrations called Samozveri (Auto-Animals), which were made for a Soviet children’s book. This series captured my imagination, and I enjoyed the silliness of the discrepancy between the revolutionary intention of making ‘photo-illustrations’ as a new, radical and avant-garde way of picture-making, while doing so by staging still lifes with cute paper cut-out figurines. My version of this is just a bit more anxiety provoking than Rodenchko’s, because I’m not very good at cutting out smiley faces properly, and because the world is a dark place these days.

LB: The Rodchenko remake is just one of several nods to moments in progressive or revolutionary pedagogy. When looking at this group together it feels like I’m being invited into a visual literacy seminar with footnotes.

ER: It’s funny you say that because at some point in the making of this show I did actually start to think about it as if I was writing an essay by other means. On paper that doesn’t sound like a great way to make art, but somehow it felt OK here. This quasi-literary approach to making the work made sense with the idea of illustration. But maybe I’m just spending too much time writing art criticism on the side and it’s starting to affect my work.

I hope I’m not starting to make bad didactic art. But then again, the work in this exhibition purposefully plays with didacticism, so it felt like a relevant thing to channel and play with. I let my pomposity run free on this one and it felt good… I trust that viewers understand that the ‘footnotes’ are just one of many ways to engage with the work. The pictures themselves are quite direct and accessible I think.

LB: Yes, I definitely think this is true.

ER: Although I deliberately make work in a very eclectic way, I’ve noticed that I often hit the same note over and over again. For a picture to work, it needs to inhabit a certain level of productive ambiguity—a sweet spot where it seems to be doing one thing while also doing another thing at the same time. I try to make pictures that work on the viewer but also invite them to put some work in. These different moments in viewing / different levels of engagement are very important because I want to make pictures that function in a compound manner.

The references/footnotes (the works, texts and images used as starting points) are really just tools for thinking in the studio. I need these tools to make the work and I’m happy to talk about these tools but they’re not there to justify what I’m doing. Instead, I think with, through and against these things; they allow me to have a dialogue all by myself—and I either abstract, combine or put pressure on them.

LB: But when we discover these textual underpinnings they do lead us to think about their sources—here maybe pedagogy or visual literacy, or education?

ER: Education and pedagogy is definitely one of the main themes of this exhibition. For the past two years I’ve been teaching a ‘photographic research’ course in the MFA in photography at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, and this exhibition is very much a reflection on my new role as a young teacher who is trying to figure it out. From this position I find myself reflecting upon my time as a student in new ways. There are so many concerns and anxieties I had as a student that I could not process at the time, and now that I’m teaching I’m beginning to understand some of these things through my students' own concerns and anxieties. It's a confronting process.

This is not the first time I’ve used my day job as a starting point. My previous solo show at KIOSK/rhizome focused on my former job as an art worker in a gallery so it felt natural to have this exhibition speak to my current job as a teacher. In fact, two of the seven pictures in this exhibition are photographs of my students. I invited them to my studio and asked them to bring whatever texts we’d been reading in class and the pens, notebooks and coffee cups they’d usually have in the classroom. We staged something that I’d noticed is a very common occurrence during seminars: that moment when someone is trying to explain something complicated about the text we’re reading and does so by using the mundane objects at hand in front of them in order to ground their argument and make their thought less abstract. The result tends to be precarious and transient sculptural arrangements of water bottles, coffee cups, books and pens. This stacking of objects intended to create or convey meaning is quite similar to what I’ve noticed in many illustrative pictures, especially in stock images. Staging this trivial occurrence when someone is trying to illustrate/illuminate others on a particular idea was interesting to me because the results are simultaneously too generic and too specific.

The two texts seen as photocopies in these photographs of the students are Craig Owens’ The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism (1983) and Walter Benjamin’s The Author as Producer (1934). Two texts that happen to question the role of the artist in society. In the photograph of the student with Craig Owens’ text, you can see a reproduction of Martha Rosler’s famous piece The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974/75), which critically deconstructs the documentary image through its relationship to text. Funnily enough, I only realized after making the picture that Florine (the student) was holding up a coffee cup and a pen in a way that mimics the idea of image vs text.

Emile Rubino, Made to Scale, 2024. Photo credit: Useful Art Services. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda

The nerdy footnote here is that, in The Author as Producer, Walter Benjamin criticizes New Objectivity photographers. Notably Albert Renger-Patzsch for the way his work makes: ‘misery itself an object of pleasure, by treating it stylishly and with technical perfection.’ For Benjamin, the presence of text in the form of a caption is necessary in order for photography to be political and to say more than ‘the world is beautiful.’ He writes: ‘What we should demand from photography is the capacity of giving a print a caption which would tear it away from fashionable cliches and give it a revolutionary use value.’ The thing is that photography inevitably trades in fashionable clichés.

There is another picture in the exhibition—titled Made to Scale—which directly emulates staged photographs by Allan Sekula (someone who was very attached to captions) that he made for his 1978-82 photo essay called School is a factory. Sekula photographed someone holding a plastic schoolhouse over a funnel filled with plastic figurines in front of the corporate landscapes near the school where he taught at the time in Southern California: he was denouncing the way in which students, regardless of what he taught them about art, would be funneled into these new corporations and become technicians... I sourced the same plastic schoolhouse online and made a very pop/toys’r’us version of this staged situation, focusing more on the gesture alone. This picture is probably the most obvious example of the way I was trying to mess around with this dichotomy between smart/critical vs not smart/not critical photography. In my experience, photography is rarely either just smart or just dumb, it’s most often smart and dumb at the same time, and that’s really the beauty of it.

LB: I hear that. I’ve been listening to Mark Fisher’s last lectures recorded at Goldsmiths just before he passed, and in one of them he talks about Lukács and his theory of reification. Reification, as I understand it, is where an ideology effectively imbeds itself so deeply that it takes on the quality of reality itself. He sees the power in undermining the naturalization of such an ideology and uncovering / describing the forces that make it work even though this new wrinkle is eventually integrated into the whole. Lukács is talking about capitalism but as Fisher was talking I kept thinking about photography. Coming home to your response made me smile. I feel that these tensions you’re interested in are related to Lukács’—where you’re employing the aesthetic of free signifying stock images to get at, or picture, the historical conditions that have brought us to this kind of generic, open-ended, repurposable signification. In a way, they’re kind of trashy, or they traffic in trashy, (which I say excitedly) and yet in another way, they function pedagogically as a kind of primer.

ER: One of Fisher’s students calls it ‘thing-ifaction,’ which I quite like. Fisher explains it in a nice way when he says that reification is the process by which ideology transforms what was not fixed (what was always in the process of becoming) into something that is seemingly permanent and therefore something that looks as if it cannot be changed. The work then is to raise consciousness so that the possibility of change becomes visible again. I guess that’s essentially what overtly political art aims to do, but I’m actually more interested in the political impotence of art, which is centered here. For this show, I was busy thinking through different historical instances of didactic and political art/photography that I admire and/or want to question: The German mid-twentieth-century artist Alice Lex-Nerlinger was concerned with making communist/feminist art that would communicate efficiently; Rodchenko and his productivist photography; Allan Sekula and his didactic documentary approach; and the apolitical or conservative ‘social aesthetic’ of stock images. It’s very liberating to take the political impotence of art (and the flat-footed aspects of photography) as a starting point for the work. I don’t mean that in a cynical or a pessimistic way. It’s more like acknowledging your own shortcomings so you don’t have to apologize for them.

LB: I get that feeling—leaning into the anti-heroic without discarding the commitment to the need for real change.

ER: Exactly. And photography has a particularly insidious relationship with ideology. There’s something about the material ‘thinness’ of photography which actually makes it the perfect container for ideology. It’s in there yet it’s so thin that you don’t really see it. It works on you without you noticing that it’s working. It seems to me that under late capitalism, the kind of photography that serves capital and the kind of photography that attempts to operate a critique of capital have more in common than it might seem at first. One has to subvert or play with the codes of the other but in the end it’s more of a feedback loop. Both are just trying to communicate and neither is able to give the viewer much agency.

So forefronting trashiness is key. I would even say that photography is the quintessential trashy medium in that it is always cheaply imitative of something else (often something better), whether that thing is reality itself or another existing picture. As I was saying earlier, photography is derivative in nature. I’ve sort of doubled down on that aspect of photography because I imitate imitations and by doing so I create something else. But my pictures don’t necessarily make something invisible become visible. Perhaps it’s more accurate to think about it as a kind of conceptual bootlegging practice. Except that usually when you make a bootleg of something, it’s because the original thing has very specific or idiosyncratic features. But here, as you pointed out, these are more like primers, what defines them is a kind of blankness. I like the absurdity of making a bootleg of something that is generic to begin with. What defines a bootleg is that it is not a ‘fake,’ it has no intention of appearing to be the real thing. This is a really interesting relationship to the real. In a very simple way, it shows that reality can be re-imagined.

For a photograph to achieve a kind of artistic autonomy, it needs to be alienated from other potential functions so that autonomy becomes its predominant quality. What I was looking for in these pictures was a way for them to sit awkwardly between suggesting function and suggesting autonomy. I think that’s a way for pictures to appear in a perpetual process of becoming.

LB: I know we’re kind of going in circles here but I want to ask one last question about the character of the appropriation of other artists’ work in your show aside from this idea of bootleg-style. I’m particularly curious about the way that open quotation brings these other historical moments into the room together. It's a little like a dinner party, but maybe more like some sort of ventriloquism or puppet show. We’ve heard how you think about the medium but I’m also curious how you feel about the legacies of these characters who were so invested in radical change?

Emile Rubino, Poverty Remix (After Lex-Nerlinger), 2024. Photo credit: Useful Art Services. Courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda

ER: I thought it would be interesting to compare—or at least bring into proximity—this moment of photography (1920s/1930s) with the 1970s, another important moment for photography’s political claim, and then draw all of this closer to the present through references to stock imagery. In some cases, such as the work titled Poverty Remix (After Lex Nerlinger), which riffs on the photograms of Lex Nerlinger, it’s more of an homage. Lex Nerlinger is not very well known, despite the amazing work she produced and the courageous and complicated life she led. She was briefly imprisoned and much of her work was destroyed; she was a very committed communist and feminist artist advocating for reproductive rights and changed her name to Lex Nerlinger later in life to make it less gendered.

I first saw her cartoonish photograms representing workers and class inequalities in a major exhibition at the Pompidou in Paris devoted to Germany in the 1920s. I had never seen her work before and these photograms made with stencils cut from some sort of tissue paper really caught my attention. They’re naive but also beautiful and somehow felt really fresh to me. In her photogram called Arm und Reich (1930) she placed the bourgeoisie on one side, with each vignette representing a different kind of luxury lifestyle or leisure activity. And on the left, she placed the poor and working class, copying each vignette three times, so that for every bourgeois there are three times as many working class and poor people.

One of the vignettes representing the poor uses the figure of an amputee with crutches which is the one I decided to emulate by simply cutting out pieces of paper which I scanned on my flatbed scanner and reworked in Photoshop to look like a photogram. The final print is a laser-exposed silver gelatin print so it’s kind of a faux old photogram: if you look closely you can easily see the traces of coarse digital manipulation. So it really is just an homage/digital remix. The title, Poverty Remix, I borrowed from a poem by Anne Carson where she talks about the ancient Greek poet Hipponax, who was known for being physically deformed and for writing verses about poverty using coarse language. Hipponax is also known for pioneering a form of meter in poetry called the limping iambs, which brings the reader on the wrong ‘foot’ so to speak by reversing the stresses towards the end of a verse. Again, I thought it was interesting to bring these two things in proximity, at least for myself, since it shows how the figure of the limping man is a consistent way of illustrating poverty throughout the ages. I was at the Getty this summer and I saw this painting by Manet called La Rue Mosnier aux drapeaux (1878), which is the typical street view with French flags on a national holiday (many painters did that), but Manet included a man walking with crutches at the side of the street as a way of drawing attention to inequities and criticize patriotic sentiments.

But there was also this thing I found to be interestingly similar to Rodchenko’s cut-out figurines, whereby both he and Lex Nerlinger wanted to make radical/political art, and both of them resorted to little paper cutout figurines. There is something cute or slightly inadequate about it in both cases, which really fascinates me since, in my work, I'm curious to see what happens when a picture embodies its own contradictions.

Bringing these different artists together in order to make my work is very similar to hosting a dinner party for sure. You never really know what kind of discussion your guests are going to have when you invite people over. But still, I’ve made it convenient for myself because none of them are here to contradict me now, so I can indeed become a ventriloquist; I can organize the dinner but in the end they’re having a discussion that I’ve spent time scripting for them. For me, the best way to honor the artistic legacies of these artists is to question them and to keep their inquiries alive.

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN & LUCAS BLALOCK

I met Diane Severin Nguyen last August as she was passing through New York on her way back home to Los Angeles having finished the second of three summers on the MFA program at Bard College. Torbjørn Rødland, an enthusiastic advocate of Nguyen’s work, had suggested we meet. Nguyen’s visceral, materialist approach stayed with me. So last winter, when the 28 year-old artist was staging exhibitions of new work in both New York (at Bureau) and Los Angeles (at Bad Reputation) I was thrilled to catch up with her and talk more about her pictures, their fugitive subjects and how these two exhibitions came together.

Flesh before Body, 2019. All images here are by Diane Severin Nguyen.

ANIMAL, VEGETABLE, MATERIAL

A conversation between Diane Severin Nguyen and Lucas Blalock.

I met Diane Severin Nguyen last August as she was passing through New York on her way back home to Los Angeles having finished the second of three summers on the MFA program at Bard College. Torbjørn Rødland, an enthusiastic advocate of Nguyen’s work, had suggested we meet. Nguyen’s visceral, materialist approach stayed with me. So last winter, when the 28 year-old artist was staging exhibitions of new work in both New York (at Bureau) and Los Angeles (at Bad Reputation) I was thrilled to catch up with her and talk more about her pictures, their fugitive subjects and how these two exhibitions came together.

Lucas Blalock I want to start with a general question about the impulse to make these pictures. Where do they come from?

Diane Severin Nguyen It comes out of a desire to juxtapose physical tensions and the failures of their linguistic counterparts. Sometimes words can claim entire bodies with their symbolic force, but sometimes they’re nowhere near enough. Working within a non-verbal space can bring about very specific material qualities relating to touch. I work from these minute tensions, of being pressed on, pierced, pulled apart, submerged, falling, twisting, which are often related to pain. And I’m curious to see if they can be empathised with photographically, or how they can be transfigured into a different feeling.

LB The images are kind of ‘grunty’: they present more as sounds than as words. And this can be set in opposition to the central activity of the camera, which has been to show things clearly in order to enable one to name a thing.

DNS There’s a poetic impulse in that sense to rearrange the language, because photography’s claims to representation and the real should be the departure point for an artist. There’s also a lot of political potential in being immersed in a medium that claims so much accuracy, which helps me think through many different texts that deconstruct essentialist approaches. For instance, my title for the show Flesh Before Body at Bad Reputation came from Hortense Spillers’ words: before the “body” there is “flesh”. Which is to say that before there’s this symbolic unit there’s the substance that makes it up and fills in the parameters of the symbolic unit, and how that dis-individuated life-form is what makes possible the individuated one. So I began to ‘flesh out’ this naming process that the camera relies on for its power, and work against its trajectory of naming bodies by starting with the nameless. I was also thinking about the word ‘impressionability’ through this other text I was reading, The Biopolitics of Feeling by Kyla Schuller, which in one section emphasised the difference between the elastic and the plastic. When you apply force to a material that’s elastic, and then you remove that pressure, it will return to its original form. When you pressurise something that’s plastic, it will be permanently changed. So there are certain words that describe these physical tensions, and how they might affect consciousness.

LB Plastic strikes me as a very sculptural term, but you’ve folded these concerns into photography. Can you talk about the delimited space of photography in your work?

Wilting Helix, 2019.

DNS I like approaching photography as a set of limitations, and also as something problematic. It forces me to begin art-making from a non-safe space, and reckon with this very violent lineage of indexicality, the pinning down of a fugitive subject in order to understand and place it. But when those tools and thought processes are exhumed or applied uselessly, we can make this Cartesian method less confident of itself. To accept the impossibility of ‘knowing’ takes us somewhere else, perhaps a more intimate place.

LB The connection to the fugitive subject is really apt because your material choices seem to be directly addressing this kind of pinning down. There’s something about fragility or flow that comes up over and over again in your work.

DNS I think it’s a lot about the provisional – almost like a material or bodily extension of ‘the poor image’ as proposed by Hito Steyerl, but actually enacting that in all of its precarity. Materials and bodies slip in and out of contexts, permeable to the elements but also political contexts. I try to echo materially what I find unstable about images, and I try to observe how materials are photographically disfigured, alienated from ‘native’ environments. I try not to rest in the place of sculptural object-making for this reason. A moment of re-birth relies on the possibility of everything shifting at once.

LB Yes, in object making, the thing is in the room with you and has to behave and remain stable, whereas the space of photography and of pictures has another set of possibilities. To me, it sounds as if you’re kind of using the photograph against itself. You’re talking about its history of violence enacted through this objectifying tradition of isolating and making a subject.

DNS It’s like a process of essentialising. Which is problematic, but I see it everywhere around me. I guess the photograph has always been used in this way, but I see people trying to assign their identities optically. And I find this to be a dangerous space. I thought we’d worked past this, but maybe we’ll never work past it.

LB There is this other way of looking at it that suggests some potential. Because we’ve used it as a parsing machine or an indexer, there’s a way in which we’re willing to read the photograph back into a bigger space as a portion of ‘reality’. This is something we don’t often do with objects.

DNS I think the reason why I’m not interested in claiming the sculptural labour in my work (even if I enact a certain kind of material experimentation) is because I’m too aware of the dispersion, the loss of authorship no matter how detailed the attempt – the permeability of an image. There’s a certain relinquishing with photography, a constant referent to an Other. And there’s a certain ownership with sculpture as an artist. I think what I’m doing is in dialogue with that dispersion, knowing that it will circulate. Even as I’m slowing it down, it’s in reaction to knowing how images can be sped up, over-circulated. But I have to be on that time scale, and the moments I harness in my work are surrounded by that anxiety. They try to reference it.

LB When I look at your pictures, I'm aware of this sense of threshold, both between the interior and the exterior, and between the animate and the inanimate. It’s something that has a particular resonance with the photographic. I was wondering if you could speak to this: how you see these thresholds, and if it’s something that you’re actively interested in?

DNS I’m always thinking about ‘life’ in this very big way, wondering how and why it’s so unevenly designated. And photography plays a crucial role in such constructions. By working with these ‘still lifes’, a traditionally inanimate space, I’m allowing myself to study the bare minimum requirements for ‘life’ to be felt. Ultimately, I’m not interested in assigning binaries between the organic and the inorganic, or indulging in the ego of an anthroprocentric status, which just recourse to human centeredness in a particularly Western way. The suspension I try to invoke is that it could be both or neither. Somehow, when the human body is removed, we get to start more immediately from a place of ‘death’, which I think photography serves much better.

LB It feels less like a trade between the terms than like a membrane, as if elements are threatening to shift into the other space.

DNS Yes, that precariousness feels so inherent to the medium itself, the rapid swapping of reality and perception. And I’m very invested in having photographic terms converse with this ‘language of life’. I believe that they’re born out of one another. Maybe this is a very Barthesian way of approaching things.

LB Can I ask you to say a little more about that – the ‘photographic language’ and the ‘language of life’?

Co-dependant exile, 2019.

DNS For instance, I’m always creating these wounds and ruptures for my photographs, this broken-ness which I think speaks to what a photograph can do to a body or to the world. But I’m also speaking to this photographic concept of a punctum, and wondering if it relies on the excavation of ‘real’ pain within a social space. I’ve depicted these evasive ‘wetnesses’. I really see photography as this liquid language, literally and materially being born out of liquids. But also, socially and economically, photography is liquid in that it can shift in value very quickly. Symbolically, liquidness can represent a very female substance and that potential immersion, like within a womb space. Historically, photography’s terms were developed alongside psychoanalytic concepts, Impressionistic painting, advertising, military technologies, and they continue to generate from/with these other sets of vocabularies. Within contemporary art, I really see the confluence with sculptural terminology as well. I guess I’m working with all those terms and trying to translate them materially.

LB This ‘evasive wetness’ you mentioned, or the way fire or burning or char act as subjects – it feels as if there are a number of ways or methods by which you get me as viewer into this prelinguistic space. One of them seems to be describing certain kinds of chemical or physical reactions.

DNS These elemental qualities provoke or catalyse moments of becoming or un-becoming. The elements speak to pressures and their transferences into new forms. Traditional Chinese medicine has a whole logic built around these types of transformations, and there’s definitely a primordial aspect to them that’s pre-linguistic. Again, it’s not revealing the ‘natural’ that I’m interested in, but more all the adjacencies that can be triggered by a photographic moment. For instance, studying photography made during the Vietnam war is fascinating to me, an era when 35mm film cameras and toxic chemicals were mass weaponised in conjunction with one another. On one hand, we have this Western-liberal pro-peace photojournalism; on the other, we have something like napalm, which is incredibly photographable. So with the fire in my images, I recreated napalm by following an online recipe. It burns in a very specific way. It’s sticky and can be spread into the shapes that I want. It lasts longer; it waits for me.

LB This makes me think about the myriad of histories you’re drawing together. Photography was certainly part of the toolkit that set the scene for the secularisation of the world and the rise of our current era of scientific, technological understanding. And this of course was produced through forceful displacements. Looking at your pictures I think about these adjacent traditions that have a stake in patterns that aren’t so ready to celebrate this turn: namely alchemy and science fiction. I’m wondering if either of these lineages play into your thinking?

DNS I like this idea you’re proposing of science fiction opposing secularisation or being displaced by it. Maybe the displacement is the part I relate to the most, the space of disaster that science fiction is always addressing, and the kind of resourcefulness that’s required in those conditions. Again, with the Vietnam War, the North was at such a great material disadvantage and couldn’t disseminate photographs at the same rate as Western-backed forces. There was a small agency set up by the Communists to glorify Vietnam through images, but the small number of war photographers would each receive a smuggled Russian camera and have something like two rolls of film for six months. There wasn’t the privilege of ‘choosing later’. So the results ended up being incredibly staged and remarkably ‘beautiful’, a twisting of poverty and political agenda. That sort of desperation to make an image that communicates is something I relate to deeply. And it’s how work in a sort of literal way, this grasping. It’s muchless rational than it should be really. It’s more desperate than I’d even want to admit.

LB I relate to that a lot. So in some ways maybe the alchemical aspect is closer because it shares a thirsty quest for knowledge.

DNS It is alchemical, though I’m not sure to what end, besides the image. But it’s also just me conducting bad science experiments. Everything is in the realm of amateur. Which I also find interesting in the space of photography. I find that echoed in what photography is: the accessibility of it and its amateurish qualities, its ‘dilettanteness’. The thing is, if I was a really pro ‘maker’, I wouldn’t be making photographs, so it’s about what I can’t do as well.

LB I understand that. It’s funny though because I hear the way you’re channelling this amateur quality, but there’s also something really seductive about the pictures. Particularly the quality of light. There’s a real fullness to them. You’re not a ‘Sol Lewitt / conceptual art’ amateur. You’re doing something else. Could you talk about that?

DNS It’s the amateur imagination, an amateur expertness. There’s a deep subjectivity to my work, and an emotion that I want to convey that usually has to do with the things that I can’t convey, and a constant attachment to that loss, like melancholia: what can’t be conveyed through a photograph. The images arespeaking to the fact that they can only exist under these terms and under these lighting conditions. And then without me, or me without them, there’s nothing. So the lighting is also very provisional. I’ll use my iPhone flashlight and I’ll use anything that’s around. have an aversion to studio lights, and everything is in this small scale. I appropriate lighting in a certain sense, looking at how light creates different situations. And it becomes a personality of its own in the way that light disturbs time. Even when I use natural light, a certain time of day, it should be an in-between moment. I think it speaks to this journalistic mood that I’m working into, even though it’s very staged. The mode is the capture.

LB Can you say a little bit more about this, because I love this idea of journalism in your work.

Pain Portal, 2019.

DNS I’m obviously aware of the lineage of journalism and it’s probably what I’ve always worked against. There’s some deep-seated aversion to street photography. But I can’t escape it, and I realised recently that this is the very mode that I take on. What does this mean for me to set up these fugitive subjects, to recreate this model of violence and photograph it? I need to admit to myself that this is the moment that I work with. And so, the more I delve into that, the more I find it a way to speak to that directly. That mode of capturing a temporary state of being is something that photography can do really well.

LB This is all coming through very clearly: the encounter in terms of subject and also in terms of picturing trauma, the sense of possibility in the provisional, and the passing ability to see. One of the things that I thought a lot about in your show at Bureau was the tension in the work between the seductive and the repulsive. There are things that actually feel traumatic – even forensic moments. But then there are other pictures where there’s much more of an invitation. I started to think about this group of situations as elements from a kind of nature film, in your attempt to capture this greater thing, a spanning from something that’s beautiful and what we might see, in the natural order, as grotesque.

DNS I think that there are these different moments of propaganda and emotionality that I’m trying to express. And it comes through in the actual installation of the images, where I worked more poetically than, say, essayistically. The way that I view a body of work holds this concurrent repulsion and beauty and different levels of accessibilities. I don’t really make these distinct series in a traditionally photographic way, but view the body of work as an actual body and part of a larger body. But I would say that most of the emotionality comes from trying to contain all the life within one image. Each image can operate on a really individual level.

LB One of the things that ‘drives them home’ is this sense of the irreversible: that though these objects themselves might not easily show what they are, it’s evident that the processes they’re going through can’t be fixed.

DNS You asked earlier about the science fiction and I wouldn’t say that my work is about any lived past or any lived future. A future is tethered to a narrative progress, which I’m really not interested in. But I do think a lot about the concept of the future of trauma and what happens during and after an event. Trauma, and how it’s rendered as an image that reoccurs in this tension that I’ve spoken about between the material and immaterial, this ordinary and potential moment – all those things add up to this kind of irreversibility. Also, at the core of my work is a deep desire to de-essentialise everything; to not let anything be trapped by someone else’s knowledge of it. So that irreversibility speaks to there being no state of purity to return to. That’s what I’m into, the non-purity.

LB The way you just described it makes me think of the tradition of vanitas. Because in a sense it’s a still-life practice you’re working through and I’m curious to read the images as still lifes engaging questions of mortality or passing. I mean a vanitas that’s denatured, pre-linguistic, more sensory than symbolic.

DNS They’re very self-portraity in a lot of ways. They’re more in that tradition than anything. They’re making active lives. I do get asked if I work in the lineage of still life and I would say that I’m only working from that to understand something else.

LB Even asking if it’s still life doesn’t feel like a good way of approaching it.

DNS The more I think about that term, the more I think about how it has this political relevance: what does it mean to have a still life?

LB Initially it was a presentation of wealth and painterly acumen. I think a lot of the things you’ve been talking about are in some ways in direct opposition to this tradition.

DNS But it is nice when things get condensed into a moment of stillness. When new changes happen, with me embracing the distance, or holding on to a physical tension that’s provoked by distance from the thing itself. That’s all within that vocabulary.

Malignant Tremor, 2019.

LB I think that this whole idea of the provisional that you’re bringing into your photography makes it so that the stillness is actually achieved in the picture making, which is different from still life. Still life will kind of stay there, whereas this is an interruption of flows of various speeds. It feels very central to the work that something is coming unglued.

DNS I think the touch of the pictures reveals a certain force that’s applied by me, the artist, in order to create this still-life. Which hopefully brings their stability into question, and also my intentions as an arranger. To me it’s a way of holding two positions at once - as a deconstructive critic of the apparatus but also as a highly subjective human artist.

LB You had two exhibitions this year, one at Bad Reputation in Los Angeles, and a two-person with Brandon Ndife in New York at Bureau. Are these two projects part of a body of work or do they feel separate for you?

DNS They were instigated by the installation requirements and conditions, by these two different spaces. I thought around those things. Obviously, it was interesting showing with Brandon because there’s this sort of content forwardness – his work also is also quite photographic in its stilling of things. With Bad Reputation I installed a circular window in the room, which is very small. There’s a more immediate relationship to the body and I felt I could invoke through that. I’d say that they’re an ongoing set – the images are part of a larger set of terms and tones that I’m piecing together before an exhibition.

LB It was interesting to see your work shown with an object maker, since your photography has been in a dialogue with sculpture for the past ten or fifteen years. But I feel your take on it is quite different. It’s not the photograph as object at all. It’s really a proposition.

DNS Because I can so easily indulge in the sculptural, or indulge in the painterly, I can abstract to a crazy extent, playing with lighting … and then I have to stop to remind myself what is the photographic moment. And that goes back to the journalistic mode, which maybe is the essence of photography and what we’ve been grappling with all of these years. In the way that I’m not interested in indexing an object that I made, or found, it’s about that object being pushed through the threshold of what photography is.

LB In the press release, there’s an interview between you and Brandon, and one of my favorite moments in the conversation is this kind of pairing you talk about between the ordinary moment and the potential moment.

DNS Which I think is when we talk about Eastern spirituality or object-oriented ontologies. It’s about this object that can be talismanic on some level. There’s this sort of spirituality to this idea that we’re here, now, in this body and we’re everything. But at the same time, I find that to be very closely related to experiencing trauma and how you’re in your body, and experiencing the feeling of being somewhere else completely. They’re two sides of the same coin. Part of me is dealing with certain political questions around how a body is identified and how you can change it. I’m interested in those narratives and those dialogues.

LB I was also really interested in your exchange with Brandon on found objects. It made me wonder about your relationship to the ready-made, and to Duchamp’s act as a kind of trauma – a shifting of categories or states of being.

DNS I started out with things that were much more recognisable. I was looking at the condition of the photograph within these objects, and I viewed photographs as being plagued by objecthood. But now, I don’t think that as much. The barriers between an object and a subject, they’re just shifting at times and it’s kind of difficult to pin down an object in that way. With the ready-made, it’s less about an object space and more about materiality in a cleaner sense – literally more about surface.

LB The flesh instead of the body?

DNS Exactly!

Liquid Isolation, 2019.

This conversation is from Objektiv #19. Objektiv is celebrating its tenth year in 2019, and this year's issues will look both backwards and forwards. For this issue, we've asked artists who have featured in our first eighteen issues to ‘pay it forward’, so to speak, and identify a younger artist working with photography or film whom they feel deserves a larger platform. Torbjørn Rødland pointed out artist DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN and chose Lucas Blalock from our editorial board to interview her.