HILDE HONERUD

Auction for Gaza !

We are pleased to announce that Hilde Honerud is offering this work from the 2009 series ‘What do you want to be when you grow up? ’for a joint auction to help the organisation Doctors without Borders which works with the people of Gaza.

Auction for Gaza !

We are pleased to announce that Hilde Honerud is offering this work from the 2009 series ‘What do you want to be when you grow up? ’for a joint auction to help the organisation Doctors without Borders which works with the people of Gaza.

We included this picture in our second issue, the series showing Palestinian children in Ramallah. Susanne Østby Sæther wrote this on the work in 2010: 'The children are photographed frontally and outdoord … in one of the few green areas on the outskirts of the city. The portraits show the children in motion, neatly dressed in casual clothes, often smiling … It is as if they were photographed before or after the actual portrait. In recent decades, the portrait genre in photography has been characterised by a neutral, registering gaze on the subject. By breaking with this expression, Honerud's images reveal an intimacy between photographer and sitter. The encounter between them is not primarily photographic, but the result of a relationship over time. The title suggests a future perspective and emphasises the closeness between the sitters and the viewer.’

The title of the work is inspired by the words of Jan Egeland, Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council, who on several occasions has described how he often asks children what they want to be when they grow up. The children often answer that they want to be doctors, journalists and businessmen. 'If they lose hope, I'm afraid they will answer that they want to be a soldier, a member of the military, a terrorist or an extremist.’ (from K7 Bulletin).

Instead of our usual riso prints, we are offering this work framed. Analog 4x5, inkjet print, mounted on capa. 121,5 x 95 cm. (With frame* 127x100 cm) 5+2 ap.

* There is a small dent on the frame.

LILI REYNAUD-DEWAR

What is it, a naked woman painted in silver print, dancing in the empty halls of Palais de Tokyo? The world is sinking and everyone says that nothing matters except what's happening in Gaza, and I couldn't agree more. And yet I go to exhibitions because art tends to make a difference, art might matter, at least I hope so. I haven't read anything about in beforehand, and am met with a lot of hotel beds and screens above them with men talking, and videos of the artist dancing in the same hall that we're in.

One Image by Nina Strand:

What is it, a naked woman painted in silver print, dancing in the empty halls of Palais de Tokyo? The world is sinking and everyone says that nothing matters except what's happening in Gaza, and I couldn't agree more. And yet I go to exhibitions because art tends to make a difference, art might matter, at least I hope so.

I haven't read anything about in beforehand, and am met with a lot of hotel beds and screens above them with men talking, and videos of the artist dancing in the same hall that we're in. The exhibition is crowded, generations have come to see it. I sit on a bench and watch with a family of three generations. We all smile at each other and at the dancing artist. The grandfather moves a little on the bench so that his leg obscures the projection. He doesn’t notice and none of us mentions it. Somehow it fits that part of the screen has gone dark.

In SALUT, JE M'APPELLE LILI ET NOUS SOMMES PLUSIEURS, Lili Reynaud-Dewar dances, teaches, writes, speaks with friends. The wall text has a dent in it, someone stuck it to the wall and left it there. With the bump. Maybe it didn't matter in the grand scheme of world events. It works as a sign of these terrible times. I read in the text that Reynaud-Dewar wants to examine the function of the artist, and that this second part of the exhibition reads like a diary in which she wants to give an account of what happened inside and outside the Palais de Tokyo (in hotel rooms in Paris, in her emotional and professional relationships, in national and international current affairs).

I go a little further in, sit down on a bed and watch one of the men talking about what it is like to live as a gay man in Paris. I try to listen only to what he says, not read the English subtitles, and I think he stresses that he knows very well that he doesn't live in a utopia, nobody does he says. The elderly lady sitting next to the me says bravo and applauds spontaneously. I raise my hands too. We do not live in a utopia.

PETER WESSEL ZAPFFE

In an envelope from the Asker photo service - dated 18 November (the year is unknown) - found in his study, there were a few strips of positive film that Peter Wessel Zapffe, or his wife Berit, had delivered to re-order some prints. The first photo on the film was taken from the second floor of the house in Asker, depicting the sun setting over Nordre Follo.

Afterimage by Marius Eriksen:

In an envelope from the Asker photo service - dated 18 November (the year is unknown) - found in his study, there were a few strips of positive film that Peter Wessel Zapffe, or his wife Berit, had delivered to re-order some prints. The first photo on the film was taken from the second floor of the house in Asker, depicting the sun setting over Nordre Follo. The next two photos are of the garden. In addition, Zapffe has photographed a class photo from when he graduated from high school in 1918, as well as a newspaper clipping from the time he climbed up into Tromsø Cathedral and proclaimed that he couldn't get any higher with the help of the church. The next time he uses his camera, it's winter. He points the camera at an overgrown, snow-covered garden.

There is a photographic-aesthetic approach to the issues that preoccupied Zapffe. And it is here that the centre of gravity of this book is to be found. His photographic archive is of almost staggering proportions, both qualitatively and aesthetically. I was struck by how Zapffe's pessimistic view of life seemed to crack precisely because of his photographic enthusiasm for magnificent landscapes, towering peaks, family, friends, animals and plants. It is ironic that Zapffe felt that nature's intrinsic value was independent of our participation, when he himself was so present in his subjects. After all, wouldn't the qualities of beautiful and magnificent nature disappear without our presence? Such anthropocentric thinking was far from Zapffe's mind. Perhaps he was not entirely consistent, but the principle was there: The magnificent and the beautiful will not disappear even if man disappears. An uninhabited planet was no accident, he argued.

This is from the book Et Stormkast Vækker Os av Dvalen (A gust of wind wakes us from our slumber) by artist Marius Eriksen. In the book, Eriksen engages in a photographic dialogue with the Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899-1990).

LINN PEDERSEN

IT IS A QUIET and early summer morning here in the kitchen. Mari and the boys are still asleep, the girls watching the classic animated version of The Jungle Book in the living room. The sun has been up for a while already, a warm breeze coming through the open window, with the sound of birds. I drink my coffee by the table, watching the city landscape.

Afterimage by David Allan Aasen:

NOTES TAKEN WHILE LOOKING AT LINN PEDERSEN’S Cul-de-sac

Linn Pedersen, Cul-de- sac, 2018 80 x 100cm, giclée print.

IT IS A QUIET and early summer morning here in the kitchen. Mari and the boys are still asleep, the girls watching the classic animated version of The Jungle Book in the living room. The sun has been up for a while already, a warm breeze coming through the open window, with the sound of birds. I drink my coffee by the table, watching the city landscape. Our view spans from Holmenkollen on the left-hand side to the city center and Nordstrand on the right, and I can just catch a glimpse of the fjord above the neighboring rooftop. Not long ago, most of this area was fields and forests. And I think about the fact that we live on top of an old volcano, along the Oslo rift, created some 200–300 million years ago. I imagine the landscape in front of me as pure nature, without the apartment buildings, houses, power lines, cars, and people. Not as the past, but as a future. Only the breeze, the sound of birds, insects, the clouds passing silently by. And then: a rattling in the bushes. A deer stepping out into a clearing, standing still as a statue, with upright neck, its ears rotating, scanning the area for predators.

*

I HAVE BEEN asked to write about an image that is on my mind, and I wonder whether I should go for a photograph by Sally Mann. Or perhaps one of Leonora Carrington’s paintings? There are several to choose from, images that appear from time to time that mean something to me in some way or other. Taking a sip from my cup, I realize I am staring at the work by Linn Pedersen, hanging on the wall beside me. And it strikes me: what about the kind of images that are always in our sight, constantly present, surrounding us in our own home? How do we see them? How do we relate to the few images we have chosen to put up on the wall? Do they become more noticeable? Or do they somehow disappear?

*

LOOKING AT Pedersen’s artwork, the opening line of Tor Ulven’s book of prose Stone and Mirror comes to mind: ‘The monument is a monument to its own oblivion.’

*

IN MAY 2018 Mari and I went to see Linn Pedersen’s exhibition Captain’s Cabin at MELK gallery in Oslo. I had been there a couple of days earlier and seen a work that caught my interest. Leaving the gallery, we agreed to purchase this photographic work, titled Cul-de-sac. We had recently moved into a new apartment, which still had an empty wall in the living room. We thought the photograph would fit that space perfectly. And it did. We kept the work there until the summer of 22. When building an extra wall to make separate rooms for the boys, we had to move it into the kitchen section.

*

WHEN A WORK OF ART is up on the wall, it seems there is no way back. There is a limited amount of money for purchasing art. There is a limited amount of space for placing the art. And there are limits to how often one can replace the art; it is not practical. One might move a table a little to the left or place the chair on the other side of the room, but better leave the art in peace; after all there is a hole in the concrete wall, or a nail in the plaster wall. And besides, the art does not wear out. We sometimes talk about replacing the stained and partly damaged sofa in our living room, but we always conclude that we should wait a couple more years, until the kids are done spilling milk, pizza, and chocolate on it. But how often do we talk about replacing the artwork.

*

DO WE TALK about the artwork at all?

*

GUESTS SOMETIMES COMMENT, saying they are nice pictures. But for us it seems as if the art has become part of the interior, like furniture. I suppose we reflect upon the images in our own way, consciously or not, not feeling the need to share our thoughts on them. It would be like commenting on the shape of a chair.

*

THE ARTWORK, taken out of its original context, is now a natural part the room, integral to the apartment. It seems one tries to make sure the image does not stand out too much. I am not sure that anyone expects the work to mean something to the people inhabiting the room, other than being nice to look at.

*

WE NOW SEE Cul-de-sac during every meal, when drawing with the kids and when reading scripts at night. We see it when we hang out our washing – the laundry rack always placed underneath. In pictures of the children in our family albums, the artwork is often captured in the background. In short, this work by Linn Pedersen has not only become part of the apartment, but it has also become a central part of our life – including, I guess, the subconsciousness of the entire family. I do not know how the children experience the art in our home, but in some way or other they will carry it with them, I am sure, just as I sometimes dream of the pictures that my parents had on the wall when I was a child.

*

THE ROOMS, the furniture, the books, the pictures, the art. A home, a shelter, a place to sleep and eat, to catch one’s breath. A gallery, a permanent exhibition, a place to think, to dream, to view the world from.

*

I LOVE THE COLORS of Cul-de-sac. And I like the shapes and forms, the bends spiraling downwards, bringing the whole image, basically calm and quiet, into motion, as if painted with large brush strokes from top to bottom. A photo taken in daylight, I guess, but presented in a kind of ghostly, dreamlike state: the inverted colors making the vegetation white, almost like frost, a background of ice holding the entire structure in place. From one point of view, it looks like a very specific sculpture. From another point of view, it is almost abstract.

*

I COULD SIMPLY SAY the image is nice to look at. That it is striking and beautiful. And leave it at that. But wait a minute. Take a closer look. The image deepens, the meaning expands.

*

HOW DID I experience the work when seeing it for the first time? Surely not with an analytic gaze. I was caught up in the mood of the exhibition, and then this image stood out.

*

A SCULPTURE, a ruin, an ominous warning.

*

IT SEEMS like a coincidence picking an artwork, regarding all the images one comes across during one’s lifetime. We see an image. We like it. The timing is right. We have some extra savings. We bring the work home. It becomes the image we see every day. It becomes decorative art. An image from which the message, meaning or mood slowly merges with the rest of the interior. The image lingers in the background, until – like now – it sort of reappears. And reminds me of something.

*

THIS IMAGE reminds me of something. Or perhaps it is more of a feeling, not a memory at all. It might even be quite the opposite: it might have to do with the future. Not a feeling, but a premonition.

*

‘WE ARE JUST a moment in time,’ laments Vincent Cavanagh of Anathema. ‘A blink of an eye. A dream for the blind.’

*

ALL THESE SONGS and all these voices, always present, ready to burst out. A song is not a memory. It is a presence. Voices always singing, though often muted, until some association turns up the volume.

*

‘TIME IS NEVER TIME at all,’ sings Billy Corgan of The Smashing Pumpkins. ‘You can never ever leave, without leaving a piece of youth.’

*

ONE LIKES the image; one brings it home.

*

TOR ULVEN´S STONE AND MIRROR is organized partially as a kind of exhibition, the texts having subtitles like 'still-life,' 'installation,' 'landscape,' 'sculpture,' 'ready-made' and 'archeologic field.' The works in Captain’s Cabin could be divided into similar categories. In a sense we are invited to a museum. We are given the opportunity to see our own age as something of the past.

*

MARIT EIKEMO’S book of essays, Contemporary Ruins, also comes to mind: the feeling of walking through the remains of constructions and buildings recently built, some of them not even finished, but already on the verge of being forgotten, bits and pieces our own communities, stories and knowledge slipping unnoticed into history.

*

I REMEMBER something now. Some of my own photographs from the 90s. One of a car wreck, another of an abandoned house, a third of a boat in a field, covered by grass. Looking at Cul-de-sac now, these amateurish images suddenly become meaningful. I see something in them I did not think about before.

*

THE MOOD of Captain’s Cabin, the combination of methods – black and white images, images inverted to negative, filters, underexposures – brought me into a state of wonder. The way houses, cars and boats were presented, created an otherworldly atmosphere, a feeling that Earth had been abandoned a long time ago. I was turned into a sleepwalker among the objects, buildings, and playgrounds, I found myself staring at strange landscapes and signs of a civilization past, nothing left but these machines and constructions, partially taken over by nature. A vision of our time depicted from a future position. I felt the distance to here and now.

*

I WAS TAKEN somewhere beyond the catastrophe. I sensed a great silence. And almost felt I had to whisper, as we moved from image to image.

*

ULVEN: 'Your own voice // on tape / it is / the reflection / that reveals / that you too / belong to // the Stone Age.'

*

I LIKE THE FACT that we get to look at art while hanging up the laundry or eating tomato soup.

*

THE THEMES and feelings that arose in the larger context of Captain’s Cabin, what I would summarize as a dark and poetic depiction of an abandoned world, are central to the work Cul-de-sac itself.

*

GROWING UP in the 80s in the rural landscape of Leirfjord, Nordland, my friends and I discovered small landfills and other remains of the past. Behind a cluster of trees, a heap of wrecked cars kept our attention for days. We played in them, broke the windows, brought parts home. We ripped off the springs from an old sofa and tied them to our shoes, and thus inventing super jump boots. We set up an orchestra, mainly consisting of percussion, beating the rusty barrels with sticks. On a fishing trip to a lake up in the mountains, I followed an overgrown path, and came upon an old house, abandoned probably a couple of generations earlier, now threatening to collapse. The sense of history and times past fascinated me, took hold, and I would later, as a student, return to take pictures of the old house and the cars. I probably did not have a clear purpose at the time, bringing my camera for a walk in the places I had been as a child. But when I look at the pictures I chose to take, I realize that there are only various ruins and other remnants of human life in the midst of nature.

*

ALL THESE THINGS are gone now: the cars, the landfills, the house, probably removed for safety- and environmental reasons. The only traces left are the photos on my hard drive. The hard drive itself will of course end up in a dumpster somewhere, the monuments of the past themselves forgotten.

*

THE HARD DISK as a brain, filled with images, potential memories.

*

WHEN MY 2022 hard drive crashed last year, some of my favorite shots were trapped inside it, among thousands of other images. At the time I couldn’t afford to recover the files, so I just stored it my wardrobe drawer instead. It is still in there, safely wrapped in plastic, and in a sense, it is a relief. All those pictures, all those memories, all those details. Do I really need them?

*

HOW MUCH are we supposed to remember?

*

TAKING PICTURES almost every day, my own project has revolved around keeping track of time, documenting the daily events in our children’s life. To keep up, I force myself to organize and edit photos each night. I spend as much time with my camera and my images as I do without them. And while the intention has been to understand time better and somehow getting closer to the children growing up, I have instead experienced the quite opposite: a mild confusion or a misconception about the events, how they happened, where and when. The harder I try to grasp time the faster it slips through my fingers. And when printing images or receiving my albums in the mail, I often think, with a naïve disappointment: is this all there was to it? Is this all that happened?

*

WOULD I HAVE understood more just participating, being present? Or by writing a diary instead of taking photos?

*

STILL, I KEEP taking pictures. An obsession. A fear of missing out.

*

I SOMETIMES imagine the girls only see my face as a camera, and that they dream at night of this black camera lens chasing them around.

*

THERE ARE TIMES when I think of photography as destructive and as an unnatural way of looking at the world and remembering it by.

*

I GUESS I TAKE the pictures for myself. It has become a habit, or an addiction. And sometimes I recall, a little shameful, what Sontag wrote: 'Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is a friendly imitation of work; they can take pictures'. But of course, I also wish for the children to have the pictures one day, having the opportunity to leaf through their early years, just as I did with mine. Still, I wonder if the large number of photographs displaces real memory. If so, it really is a paradox if we think the photograph is meant to preserve a memory. And by the way: What memory? Whose memory? To what purpose?

*

WHEN THE LINE between looking and taking a photo becomes blurred.

*

A PHOTOGRAPH is always somewhere between a window and a mirror.

*

IN METTE KARLSVIK’S novel Darkroom, the protagonist, addressing her father, says: 'My sister and I have lots of photographs to remember our childhood. We do not have just one picture, or a handful, like you have: You have the picture from baptism, a class picture from school, and one from college. My sister and I have albums and walls covered with memories. We get a more nuanced picture of our childhood. Or do we let our memories become more shaped by photographs than your memories are.'

*

IF YOU HAVE only one photograph of yourself as a child, does your life seem poorer or richer, your memories more or less valuable?

*

A COUPLE OF hundred years ago there was no other way of recalling one’s past except through stories, drawings, objects, and other 'natural' ways of remembering. I imagine people recall their relatives and friends as voices, talking, crying, laughing, or singing. Always there, always present.

*

I TRY TO imagine a modern society like ours, only without cameras, mobiles, and photographic images.

*

MY CHILDHOOD FRIENDS and I experiencing the world by just being present.

*

PHOTO ALBUMS as personal ruins.

*

WHEN I AM in doubt, Mari tells me I must keep taking the pictures, that it is worth it, that I should not feel bad about it. The girls will appreciate it one day. And I am all good to go again.

*

AND BY THE WAY, I am not sure if preservation of memory is what interests me in family albums. I think it is about placing oneself in time and in a context, being able to tell a story, make connections, finding one’s place in the world. And this is something worth passing on. An image as a starting point from which to tell one’s story.

*

PHOTO ALBUMS as mirrors.

*

WE LOOK AT the art on our wall and see something. The years go by. We look again and see something else.

*

I REMEMBER a painting from my early childhood. I thought it was a picture of my father and my older brother and sister. When rediscovering the painting, twenty years later, I realized the characters had no relation whatsoever to my family.

*

CHILDREN INTERPRET art the same way adults do: with their own frame of reference.

*

I SHOULD ADD: My parents still have that same picture on their wall. Moving from apartment to apartment, from house to house, they always kept the same images. Some disappeared in time, the rest were kept. The pictures at my parents’ house reminds me of the rooms we have left behind. The pictures on their walls evoke memories of my early childhood in Sweden.

*

THE ROOM contains the picture, and the picture contains the rooms. We never travel very far; the past is always right by.

*

MARI’S PARENTS became friends with the French-Polish painter and printmaker Tomasz Struk in the 70s. They bought several of his prints, had them framed and put up on the walls in their house in Homme, Vigeland. They even bought more prints than they had room for, as a way of helping him out, and then passed these on to friends and acquaintances. Today the art of Tomasz Struk in Norway is therefore heavily concentrated in the Mandal area. When Mari moved to Oslo into her first apartment, she brought a couple of prints. And now, years later, Struk’s prints have ended up on our walls. Mari says that the pictures carry some of her childhood with them. And I feel that, in some way I am taking part in it, seeing what she has seen.

*

IN MY VIEW Cul-de-sac primarily deals with what remains, showing how the most familiar objects grow mysterious with time. While the theme of mortality is inherent in all photographic work, Pedersen’s image not only addresses this theme more explicitly, but raises some important questions as well.

*

THE ARTWORK as a mirror. Me sitting here, looking at myself.

*

THERE WAS A SENSE of abandonment in the series of images in Captain’s Cabin, emphasized by the depopulated scenes and scenarios. This sense is even more notable when the one image is taken home. The separate works communicated with one another, perhaps about their collective abandonment. Now this work hangs all alone on the kitchen wall, mumbling monotonously. I am sure it is some kind of warning.

*

OR THE IMAGE, presented with inverted colors, might simply be showing a water slide after closing time. As Ragnhild commented, when visiting: Cul-de-sac made her think of someone she met once who had broken into an abandoned amusement park at night.

*

OR IN THE PERSPECTIVE of the 'exhibition,' the slide as a gigantic object in an outdoor museum, framed by a fence: 'Do not touch the art.'

*

A POST-APOCALYPTIC IMAGE, a contemporary ruin, a comment on society, Cul de sac as metaphor for a difficult situation, the peak of our civilization as loss of perspective and meaningless entertainment, 'amusing ourselves to death', or just a playful piece of art.

*

THE SERIOUS themes contained in Pedersen’s image is, I think, paired with a sense of humor, or at least an absurd dimension. We could see the title of the work quite literally: for what is a water slide except a dead end?

*

HAVING WRITTEN my master thesis on Tor Ulven, and for years read his texts, his images appear in my mind from time to time, like now, looking at Cul-de-sac. And even though they are literary ones, I find them just as vivid as any visual artwork. I could as well have written about one of his literary images.

*

OR THE OTHER way around: Cul-de-sac, even though an image, speaks to me in the same way that Ulven’s texts do. I often think about seeing 'death / everywhere' with a gaze that is 'rotten. Clear. Non-political.' A kind of meditative adjustment, like putting on a pair of memento mori-glasses. When paying that visit to MELK in 2018, I felt a strong relation between this lesson from Ulven in Pedersen’s works. There was an image of a toy skeleton of some kind. This classic memento-mori motif had a cartoonish effect in this setting, and forced me to shift the perspective from this little human remain to a larger and more comprehensive threat.

*

A WATER SLIDE on the wall, a memento mori, not only telling me that I am mortal, but hanging there as a monument to the vulnerability of Earth itself. Of our descendants and of all species. A question of responsibility. An image of our age as past containing a strong warning about the future.

*

I FORGOT. We do replace our art … When we moved Cul-de-sac from the living room to the kitchen, we had to remove one of the two works by Tomasz Struk. We attached Pedersen’s work to the screw already in the concrete wall and placed the Struk on the bedroom floor, up against the wall, together with some other pictures that we do not have space for. The Struk-print was a collage showing two zebras and a living room, a sofa, and the skin of a tiger on the floor, a comment on modern times and our relation to nature. The image was replaced by a new one, telling part of the same story.

*

WE WERE GOING on a trip to the Mullsjö-area of Sweden, driving from Nödinge where we lived back then, to visit a friend of my parents (who by the way was an artist whose pictures today are on the wall at my parents’ house). There was a water slide there. I was about four years old, and what was supposed to be fun turned out to be frightening. I took the ride with my father. Coming down into the pool, my eyes and mouth filled with water, I cried. Still, I wanted another go. I cried once more. And so on. The thrill and the pain. The thrill and the pain. Amusing myself to tears. Not a dead end, but a meaningless circle.

*

TO A FUTURE human being – or an alien life-form, for that matter – how would this image be approached, as an artwork, or as an actual water slide? Would they come walking through the landscape and pause, wondering if this was a construction of practical use? A kind of aqueduct? A monument? A temple? An image of a deity? Or less hypothetically: the water slide standing in a clearing. A rattling in the bushes. A flock of birds taking off from the construction. A deer stepping out from among the trees, and then, standing still as a statue, with an upright neck, the ears rotating, scanning the area for predators.

*

I TOOK THE girls for a walk to the top of the hill. I brought my camera. There is a concrete construction up there, a small tower painted with graffiti, which served as a backdrop for my photos of the girls. I have been up there several times, but I have never been able to figure out what function the construction once had. I discover a pamphlet published online by local historians. I find that it is probably the remains of a trigonometric point, built sometime between 1904 and 1909, used for land-measuring purposes. In another source, a man recalls a walk on the hill with his father in the 60s, that there was a red light on top of the tower, and his father told him it was a signal for airplanes headed for the Fornebu airport. Yet another entry refers to the construction as a lookout point. Not long ago this construction had a meaning and a function. Now it is a meaningless monument in the middle of nature, the knowledge nearly lost, the information hard to come across: on the verge to becoming a mystery.

*

I THINK OF the exhibition at MELK. I think of my own photos. I think of Tor Ulven’s texts. I think of watching Aftersun with Mari earlier this summer, a gripping, emotional experience, now the concept itself accentuated: the video footage documenting the past, and the memories risen from the footage. I think of the old cassette I found in a box when cleaning out the shed, one that my father recorded when living in Gothenburg, of him playing the guitar, and singing. I listen to the tape, the song, the fragments of conversation, and then: a characteristic laugh. My parents’ old friend BJ, whom we visited in the mid-90s in the Arizona desert where he lived with his family. Another recording on the tape, the voice of a baby: my little brother crying. A forty-two year old cry.

*

THE STRANGE presence of Tor Ulven´s voice on the Vagant-recording from 1993, emphasizing the theme of the poem he is reading: 'Your own voice // on tape / it is / the reflection / that reveals / that you too / belong to // the Stone Age.'

*

MARI CAME HOME with a USB-stick, a digital transfer of the home videos her father made in the 80s. We watched a clip. Or: I watched, while she remembered. Or, as she put it, she always thought these were her own memories, but what she really remembered was these images. The guy in the video store told her: be sure to make a copy. I think about all the copies out there, copies of copies, all the effort to keep the past in the present. I think about everyone who every day bring the past to life for a moment. Then letting it go, forever. And I think: what about the future?

*

I THINK OF my first rooms. I think of the images on the walls throughout my childhood. I think of Gaston Bachelard’s book The Poetics of Space. I think of Frances Yates’ book The Art of Memory. I think of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. I think about myself namedropping. I think of humans becoming oral storytellers becoming writers becoming image-makers. I think about how a photograph will make you remember the event. But also, how the photo will make you remember something else. I think of how one image might contain a multitude of images. I look at Cul-de-sac and think about how an image will get your thoughts and your text flowing.

*

I GUESS IT’S just me, but the gallerists, the museum intendants and the other visitors at different artist spaces always distract me. I have a hard time to focusing. Perhaps some art should be viewed at home, in peace, on the walls, in books, on the computer screen. While some images talk directly to you, some art might require a kind of meditation that take years to complete, or perhaps a lifelong meditation. Getting to know the image. Getting to know yourself.

*

I THINK about what an image opens in me, and it makes me wonder about whether I am still writing about Cul-de-sac or if I have gone off track.

*

'IN A LITTLE while I’ll be gone' sings Thom Yorke of Radiohead. 'The moment’s already passed. Yeah, it’s gone'.

*

I THINK of the scene in Terminator 2 where Sarah Connor envisions the apocalypse, the nuclear explosion hitting the playground. The catastrophe has already happened. But still, she fights to prevent the catastrophe. I think of the Arizona desert and BJ laughing. How a voice heard over thirty years ago sounds real and alive in my mind. I remember they had a pool they did not use, it was dry and empty, covered with leaves and dirt, lizards running up and down the walls. A ruin in their own backyard. I think about species going extinct on a day to day-basis. I remember the orang-utan watching us at the Kristiansand Zoo this summer, and feeling regret at taking the kids there. The apathetic orang-utan, separated from us by a glass wall. The orang-utan understood. I am sure it understood it all. The story of humankind, the story of violence and expansion, of destruction and dominion. And somehow, I felt responsible for its loss of freedom, of life. I think about the future scenarios still to be prevented. I think about John Berger’s text 'Why Look at Animals.' And I think about what attitudes would change if one knew, or if one had the imagination to envision the end of the world.

*

I REMEMBER unwrapping Cul-de-sac, the kids popping the bubble wrap. The artwork leaned up against the wall before we put it up. The total silence of the image. Not even the sound of birds. No one soon to stroll past the monument. Perhaps the wind might sweep by. But no one will be there to hear or feel it. I think about our world, depopulated. I think about the planet.

*

I THINK about my children when I no longer exist, having left them tens of thousands of photos, traces of what I saw and how I looked at the world. Traces of the children themselves. Perhaps it will all be meaningless to them. Or just too much to work their way through. Or perhaps it will be of some use, entertaining at least. I think about what other ruins they will inherit, what will be left for them to interpret that we now take for granted. What extinct animals will be added to the list. And looking at Cul-de-sac, I also wonder who of them would want to inherit this work of art. If it has made an impression. Talking to Martin B. at the office, he told me that when his grandfather passed away, and the house was being sold, his mother insisted on having the one picture that had meant so much to her, one that felt as part of her childhood.

*

ARTWORK ON THE WALL as identity, as feelings, as evidence, as an extended family-album of shared or personal memories.

*

I WAS RAISED evangelical and was taught that Adam and Eve were historical persons, that humanity had existed for 5,000 years. I was also told that Jesus would pick us up at any time. I think that carrying a mental time span like that somewhat frees one from responsibility. The faithful will be saved in the end anyway, and there will be ‘a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth have passed away.’ One day, or rather gradually, I must have felt a change, feeling the responsibility of being a part of the slow-moving nature, no longer a part of a divine plan. Another version of me, walking through the landscapes of Captain’s Cabin, might have read the rapture into the images. Jesus having picked up all the believers. The horror scenario of the unbelievers left behind.

*

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC work Sixtytwo Gasoline Stations by Jan Freuchen shows images of 62 different stations overturned by storms and hurricanes. The artist himself says he was struck by the paradox in that the gas stations had collapsed because of the extreme weather, which the combustion of the gasoline itself had helped accelerate. When visiting the new National Museum recently, I stood there looking at this series of images. Of course, I saw only ruins. 62 contemporary ruins. An image of an age soon to be over. While the gas stations in Ed Ruscha’s work Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) were functional, and Freuchen’s Sixtytwo Gasoline Stations (2017) were destroyed, there will come a time when all gas stations will be scattered throughout the face of Earth as mysterious constructions, temples, shelters, overtaken by nature and the animal kingdom. I think of the lion in 12 Monkeys walking high up on a building, covered with snow and ice. Then I hear the music from The Jungle Book coming from the living room, remembering the abandoned temple with the orang-utan King Louis sitting on a throne.

*

IN MY TEENAGE years, the nearest gas station was right down the road, in Leirosen, by the river running into the sea. We bought candy there and rented VHS movies, and when I got my moped, I filled up the tank there. It is strange now, coming home, seeing only asphalt and concrete remains where the fuel pumps once stood. In summertime, this place was crowded, or so I remember it, locals and tourists inside and traffic outside, this being the road between Mosjøen and Sandnessjøen at the time. Now there’s a tunnel going straight through the mountain a little further up the river, and no one ever comes here anymore. There is a feeling of abandonment, of something missing. And I do not think it concerns only my personal past. It is not the pure nostalgia of Cliffhanger, Hockeypulver, Bugg, Kræsj Pink. This is also about communities dissolving. The ruins of recently inhabited houses. The abandoned shopping streets and the new shopping center. The closed rural schools. The small farms forced to leave the work to large-scale production. This has to do with political decisions. With certain ways of living. With taking care of nature, each other, the animals, the living creatures of the Earth.

*

I SEARCH FOR 'free negative scanner app,' download one, and take a picture of Cul-de-sac with my phone. After processing, the picture shows the laundry on the rack in negative colors, and Cul-de-sac on the wall above, now with a sunlit, blue sky, green trees in the background, and a turquoise slide. As if telling me there are other possibilities, that there still are alternative futures.

*

EVEN THOUGH WE believe the catastrophe has already happened, and even though we believe the end of the world is unavoidable, there is still a choice of limiting the damages for they who are born tomorrow, within next year and in ten years.

*

WHY IS IT so hard to imagine a world without us? To imagine the existence of those who lived before, or those who shall live after we are gone? Why is it so hard to imagine the end of everything? Religious doomsday visions and disaster movies are part of our culture, but we have difficulty accepting the fact that life on the planet is slowly collapsing. And that may be problem: while technology and our knowledge of how to behave are changing too fast for us to keep up, the destruction of the planet happening too slowly for us to comprehend. The end of the world is not about fire and brimstone. It is an almost invisible, silent death that is happening as we speak. Perhaps a mythical image of The Beginning might be an appropriate image of The End: 'And the spirit of God hovered over the waters' as the last sentence of the last chapter. A simple image. The Earth. Desolate and empty, covered with water. And a wind making waves over the world.

*

ULVEN: 'Sit beside me / my dear, tell me // about the time / when I no longer // exist.'

*

WHILE WATCHING a seagull soar past the kitchen window, I remember reading that this area, this hill, this old volcano, now 200 meters above sea level, was once covered with water. Instead of a seagull searching for leftover food, there would be a Pliosaurus hunting for fish around this underwater hillside. In some million years, this landscape might once again be covered by the sea.

*

I IMAGE a series of 'Sixtytwo Water Slides.' I start googling 'Abandoned water slides' and 'Abandoned water parks.'

*

LOOKING AT ART or reading books will not get us anywhere in itself. But new perspectives might make us organize differently, vote, talk and write differently. I see a glimmer of hope here. The art that opens our imagination to possible versions of the future is an important addition, or even a path, to explicit political art and activism. We need to imagine the horror. And then we need to strengthen our hope.

*

THE SMALL PASTS AND FUTURES of our private lives, our family lives, our children´s lives and the collective past and futures of the Earth: They are all connected, impossible to separate.

*

IN SHORT: we are here, right now. Between not being here and not being here.

*

IN THE ever-increasing stream of visual impressions, at a time when we seem to not notice that we live in an image-based world, visual art could play a crucial role. Photographic works that insist on their uniqueness and strength as an art form, and that address both with how we look at images and of what it means to be here right now. We need images that speak of our time in a different way than the online news or through what we see scrolling down our Instagram-feed, we need works that make us pause for a while and just keep looking at that one image.

*

REST OUR EYES by looking, rest our minds by thinking, recharge by meditating.

*

PEDERSEN’S WORKS stand out visually. So, we pause. And we take our time. Because we notice something. There is a seriousness in the expression. We ourselves are taken seriously. The works seem to have been created out of necessity. The feeling that something is at stake. Her art has lasting qualities. On the one hand it is open and timeless, and on the other hand she makes us see our own time from unexpected angles. We have all seen a water slide before. But not like this. We have all seen our world before. But not like this. Her art makes us reflect not only on photography and its relationship with the world, but also on our place in it.

*

SOMETIMES I REACH for Tor Ulven’s book of collected poems on the top shelf to get a quick fix of existential insights on time and mortality. Or just to get a feeling of time. From now on I will probably step into the kitchen and just pause in front of this photograph for a while, to approach the same kind of feeling.

*

Cul-de-sac merges with the background and completes the kitchen section. A new day is about to begin. It seems it will be a hot one. Maybe we should go to Frognerparken, and introduce the kids to the water slide?

The lines from the Ulven poem ‘Your own voice // on tape …’ were translated into English by Benjamin Mier-Cruz as part of an interview published on thewhitereview.com. All other translations are my own.

Linn Pedersen - Captain's Cabin - MELK

SHIRIN NESHAT

It is a meeting at a crossroads. A man walks towards a woman on the other side of the road. They sneak glances at each other as they pass, and keep on walking.

One Image chosen by Nina Strand:

It is a meeting at a crossroads. A man walks towards a woman on the other side of the road. They sneak glances at each other as they pass, and keep on walking. He stops and looks back at her and smiles. But they keep on walking, both headed to the same place, though taking different routes.

Next scene: The man and woman meet again, with a curtain between them; a mullah is preaching about chastity. They look at each other through the blinds. At one point the woman has heard enough and leaves. He follows shortly afterwards, but again they walk away from each other. I want them to meet, we all do, but they never will.

The two-channel video Fervor by Shirin Neshat from 2000 was filmed in Morocco, but purports to be Iran. Shown now in the 30-year jubilee show Before Tomorrow for Astrup Fearnley in Oslo, it is unfortunately still topical today. I see it after having had a swim, and think about the two never meeting while walking home, my wet hair made wetter still by the summer rain. I think about my luck to be living as a woman here, and not there. And then I remember a recent conversation with a friend about the chances he felt he’d missed, and the imaginary family life he’d envisioned. He’s fifty and says it’s over; he doesn’t think it will ever happen for him.

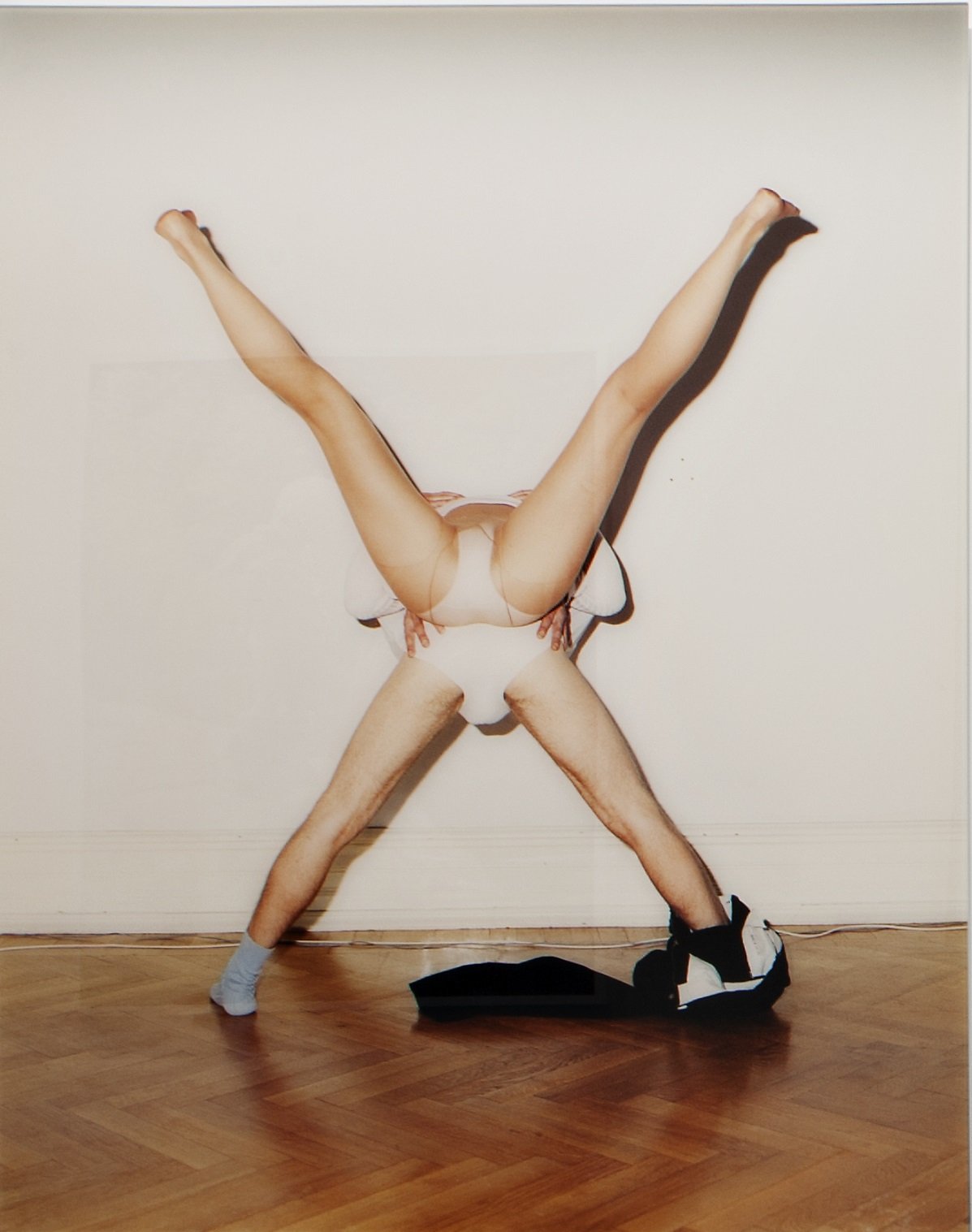

Also on view in Before Tomorrow is Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff's 1999 photograph Mom and Dad Are Making Out. Two human bodies form a cross, the woman balanced on the man’s back with her legs in the air. The joyful colour contrasts with Neshat’s passionate black and white. These two people, mom and dad, did actually make it together. We can still make it too.

Still, Shirin Neshat, Fervor, 2000

Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff, Mom and dad are making out, 1999.

TALA MADANI

Rushing through yet another art fair last fall in Paris, a small canvas stopped me dead in my tracks. Iranian-born, Californian by choice, Tala Madani is an artist I first heard about in painters’ studios.

Afterimage by Lillian Davies:

Rushing through yet another art fair last fall in Paris, a small canvas stopped me dead in my tracks. Iranian-born, Californian by choice, Tala Madani is an artist I first heard about in painters’ studios. Artist Xinyi Cheng, for one, is a fan. Inside the fair tent, set up over the park and playgrounds of Champ de Mars, I’d spotted one of Madani’s latest canvases: a muddy zigzag in glossy oil paint on a white gessoed square.

‘She’s made an abecedarium out of them. This one is Zed. From the Shit Mom series,’ a fashionable British gallerist brightly explained. ‘There’s one for each letter of the alphabet! Would you like me to send you more information?’Scribbling my email address in her tanned leather notebook, before admitting I’m a writer, not a collector, I asked the price: ‘30,000 euros.’

Warmly embraced by the art world, in the language it speaks best, Madani is nonetheless a skilled social commentator, taking aim at received ideas about value and gender as perpetuated in traditions of painting and motherhood. With children of her own, Madani explains that her Shit Mom character emerged after her first was born. She was exhausted by a certain sentimentality that had crept into her work, and wanted to come to terms with the prevailing model of a sacred Mother and Child.

In addition to her ABCs on canvas, Madani’s created a single channel animation featuring her Shit Mom character. Her gallerists helpfully shared a link to the work on Vimeo, but it wasn’t until this spring, tunneling through a press visit at Palais de Tokyo, that I saw this work projected full size. Until January 2024, Madani’s Shit Mom Animation 1 (2021) will illuminate an entire gaping room of Hugo Vitrani and Violette Wood’s group exhibition La Morsure de Termites (The bite of the termites).

Made with wide strokes of earthy brown, Madani’s animated figure betrays a feminine silhouette. Her hips flare wider than her shoulders. She’s given birth, voie basse. And she’s tired. Moving languidly as if from one room to another, her animated form sways across a series of static interior photographs. Reminiscent of the Hearst Castle or a gaudy spread from a late 70s Architectural Digest, Madani’s Shit Mom smears across a white bedspread, beige couches, and a lacquered dining table surrounded by mock Old Master paintings. She marks nearly every item of furniture with her signature burnt sienna. Like a dung beetle, rolling her ball of feces for food and breeding (symbol, for the ancient Egyptians, of the rising sun), Madani’s Shit Mom radiates across her bourgeois landscape in colors of excrement.

For her canvases in this series, Madani employs an unctuous pigment, like chocolate frosting on a child’s birthday cake. And she replays this sticky glimmer in her animated film. A recipe for a nauseating attraction and repulsion, Madani’s glossy surface juxtaposes gluttonous desire with visceral disgust at an eventual defecation. Reveling in the play of painting, the beauty of this creature is that she is both destructive and fecund. Like a heap of steaming compost, she is nutritive. Armed with comedy and a fertile motif, Madani tackles motherhood’s oppressive myth making: injunctions of purity and serenity that persist across cultures and over time. Shit Mom is a foil for la Madonna. And a Virgin? Far from it. She acts on her desire for sexual pleasure.

This spring, writer Jiayang Fan published her story ‘A mother’s exchange for her daughter’s future.’Fan describes shit running down her mother’s leg as she lies in her hospital bed, nearing the end of her days. Trying to finish her first book, Fan observes her mother’s impatience as she points her frail fingers at an alphabet card: DEADLINE. Her question of just when Fan will get her creative work out is also a question about whether she’s ready to let her story show itself in colors of an overflowing colostomy bag and a soiled vitrine. Fan’s story is an exquisite attempt. And like the place she writes from, Madani also works from the insides, what’s left. Because, that, really, is all we’ve got. It’s fertile, shit. The stuff of a life’s work.

Installation images from Shit Mom Animation 1 2021, by Tala Madani at Palais de Tokyo taken by Aurélien Mole.

MARIA PASENAU

On my mind an image by Maria Pasenau, intimately exposing herself and her fiancé in a show about herpes. Standing in a small cubicle in the gallery’s cellar, covered in wallpaper containing a mix of patterns and positive and negative portraits of the fiancé, feels like being in their love-making room.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

On my mind an image by Maria Pasenau, intimately exposing herself and her fiancé in a show about herpes. Standing in a small cubicle in the gallery’s cellar, covered in wallpaper containing a mix of patterns and positive and negative portraits of the fiancé, feels like being in their love-making room. On the three walls, many photographs and drawings are installed salon-style, showing viewers absolutely everything of their relationship, and I find myself worrying about the exposure. Many of the photographs depict their genitals in close-up. I feel safer laughing over the drawing of the mind map about what’s good and bad about herpes, where every thought reads:‘It Hurts’.

There’s a triptych where Pasenau undresses in a field full of yellow flowers. The way her garment gets stuck on her head in the last one also makes me smile. On the other wall is a picture of her partner in a similar field. Their love for one another is so clear. These works ease the Peeping Tom feeling I had in the rest of the show. I felt like a voyeur, but honestly, who owns the gaze here? She does, because she’s behind the camera as well as in front of it, and I wonder why I can’t see a young woman in love, having sex, without thinking protective thoughts about how she should cover up, show less, hide the images in private albums, when in fact maybe she should do more of this. She’s taking over from Goldin and others working with slice-of-life self portraits, continuing to challenge our inhibitions and prejudices. Enough of my scepticism. She’s got it right.

Maria Pasenau, In the middle of my actions, 2022.

SHEYI BANKALE

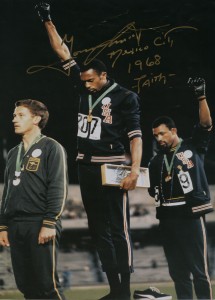

Ever since I first came across this image, it has been on my mind. Charged with human and civil rights protest, it played with the idea that Smith and Carlos gave us the answers, with just one symbolic gesture. The gesture rose questions of belief, courage, sacrifice and dignity.

1968 Olympics Black Power Salute, Mexico City, signed by Tommy Smith, photographer unknown / AP, gifted to Autograph ABP by Iqbal Wahhab, courtesy of: Autograph ABP

Afterimage by Sheyi Bankale:

With the euphoria of the London Olympic games, photographs of sporting moments form fixed notions of symbolic endeavour that inspire and create role-models. The one photograph that captures this notion for me best, is the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute by athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony at the Mexico City Olympic games.

Ever since I first came across this image, it has been on my mind. Charged with human and civil rights protest, it played with the idea that Smith and Carlos gave us the answers, with just one symbolic gesture. The gesture rose questions of belief, courage, sacrifice and dignity. Under the gaze of the world, Smith and Carlos faced their respected flag and listened to the Star-Spangled Banner anthem. They both raised a fist, coated in black leather gloves, penetrating the dark sky until the anthem had finished.

The emotional experience conveyed in this symbolic act, following years of training and commitment as athletes, will forever resonate with me.

WOLFGANG TILLMANS

“Sloppy has always been good, meant sexy,” Eileen Myles wrote in her iconic book Chelsea Girls. I would agree with Eileen. Her statement is contemporaneous with when Wolfgang Tillmans was photographing youth culture, in the first half of the ‘90s. His images depict people who are sloppy in the most gratifying sense: casual, heedless, uninhibited.

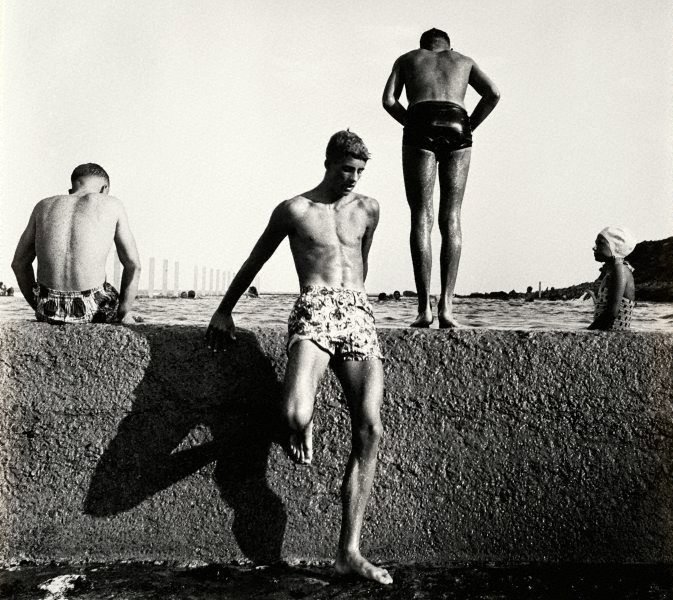

Wolfgang Tillmans, Adam’s Crotch, 1991

Afterimage by Sarah Moroz:

“Sloppy has always been good, meant sexy,” Eileen Myles wrote in her iconic book Chelsea Girls. I would agree with Eileen. Her statement is contemporaneous with when Wolfgang Tillmans was photographing youth culture, in the first half of the ‘90s. His images depict people who are sloppy in the most gratifying sense: casual, heedless, uninhibited. He captures a state of being, a shrugging feeling that trickles down to posture and style. The Berlin Wall had come down, and ideas of structure and stability wobbled profoundly along with it — what could be re-conceived? Everything. Anything.

Tillmans counters photographic flatness through sheer proximity to the body, in almost invasive close-up: right up in an armpit with sweaty tufts of hair, right up alongside the shimmer of sweat slicking the clavicle. In Adam’s Crotch, ripped, fringed, scuffed, hole-riddled jeans go beyond heavy wear to a reflection of living hard: thighs rubbing together for all-consuming movements and reckless experiences, which translate into garments shredded thin, patchworked back together — and still are coming undone. Whatever party has been cut out of the frame out can still be felt from the tight crop. Hands resting lightly, underwear showing indifferently: there’s a serenity to not fretting about what looks appropriate, because propriety is a myth.

The photo is simply a display of being comfortable in a laissez-faire setting; it’s observing leisure and idleness. A close-up of a crotch could ostensibly be an aggressive move, but here it speaks to ease between photographer and subject, the camaraderie of not having to be polite and careful: that Adam’s boundaries melt into Wolfgang’s.

ZOE LEONARD

Consider American artist Zoe Leonard’s recent photographs, presented in New York in an exhibition titled In the Wake. They depict family snapshots from the period after World War II when her forebears were stateless. The original images, taken as her family fled from Warsaw to Italy to London to the United States over the course of more than a decade, offer scenes of intimacy that contrast with the era’s international clashes and their messy aftermaths.

Afterimage by Brian Sholis:

Consider American artist Zoe Leonard’s recent photographs, presented in New York in an exhibition titled In the Wake. They depict family snapshots from the period after World War II when her forebears were stateless. The original images, taken as her family fled from Warsaw to Italy to London to the United States over the course of more than a decade, offer scenes of intimacy that contrast with the era’s international clashes and their messy aftermaths. Leonard, in re-photographing the originals, opted not to reconstruct lost moments, to close the gap between then and now. Instead, she examines the earlier photographs as printed objects that bear physical evidence of their own histories: we see scratches and other blemishes, edges of paper curling upward. Sometimes, too, Leonard aims her camera from an oblique angle, shrouding the original subject with a splash of reflected light and revealing a wavy postmark. (These objects made the same journeys as their subjects.) She flips one photograph to document its inscription. “It’s not that one sees less,” Leonard has explained of these works, “but that different information becomes visible.”

Leonard’s artworks are in the “wake” of the originals in multiple senses. A wake is the path behind a ship marked by choppy waters – a useful metaphor for migrants seeking safe harbor, as the pictures’ subjects are doing, or for the compositions, in which the originals “float” against featureless backgrounds. A wake is also the act of keeping watch with the dead, of meditating on lives as they were lived. For every migrant who forged a life in a new home, as did some of Leonard’s family members, there are others who could not. And to “wake” is to come to consciousness, to become alert to the world around you when before you were unaware. The narrative emphasis placed on their subjects’ statelessness ensures the pictures’ relevance in our present moment of geopolitical instability and its attendant migrations. These intimate pictures are linked to – awaken us to – some of the broadest and most pressing social concerns of the day. Many of the original pictures are bounded by thin white borders. By re-photographing them and placing them within this conceptual and narrative frame-work, Leonard ensures that the meanings they convey are not similarly restricted. We know little about the lives of the people depicted, the knowledge of which remains the province of Leonard and those close to her. But in imagining those stories, empathy compels us to relate at both intimate and grand scales.

JULIAN FAULHABER

I’m currently looking a lot at images like this, which are in a kind of hybrid state between the hyperreal and the abstract, between fact and fiction. It is perhaps not this particular photograph by Julian Faulhaber that fascinates me, but rather the type of photography it represents, images that with crystal clear sharpness depict something with a detailed and zealous attention and yet does not really reveal anything.

Afterimage by Jenny Rydhagen:

Tankstelle, 2008, © Julian Faulhaber / VG Bildkunst.

I’m currently looking a lot at images like this, which are in a kind of hybrid state between the hyperreal and the abstract, between fact and fiction. It is perhaps not this particular photograph by Julian Faulhaber that fascinates me, but rather the type of photography it represents, images that with crystal clear sharpness depict something with a detailed and zealous attention and yet does not really reveal anything. The image is as expressive as an architectural rendering and I find it both repulsive and attractive this lack of signs or clues. I don't quite know where to fix my gaze in this image, it sweeps over the polished surfaces in search of a little friction, for a rustle on the ground, a withered strand of grit, a crack in the perfection, until it is finally sucked into the darkness somewhere behind the petrol pumps. I’m trying very hard to get into a place I don't really want to be.

PATTI SMITH

This photograph of young Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, was taken by an old man with a box camera on Coney Island in 1969. The image is used on the cover of Smith's book Just Kids, which revolves around the relationship between the two, and on how they together began their respective artistic careers.

Afterimage by Ingvild Langgård:

This photograph of young Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, was taken by an old man with a box camera on Coney Island in 1969. The image is used on the cover of Smith's book Just Kids, which revolves around the relationship between the two, and on how they together began their respective artistic careers.

I have seen several iconic images of these two, together and apart, but this one is still on my mind. There is something snapshot-like about it, while at the same time it's a fantastic portrait. You can see how it was them who initiated the image, wishing to preserve a moment in time.

There's something reserved and graceful and at the same time mysterious about them, as if they already know something, something great and fantastic. The picture was taken before either of them became famous artists in their respective fields.

It is of two young people, hoping to become something, but right there and then only hanging around. They wanted to document themselves then and there, and had, according to the book, put a lot of effort into their appearance.

That the picture is from Coney Island, is of course no coincidence, and the place becomes here, as often else, a character in itself: the very incarnation of nostalgia connected with the future. Although my reading is of course charged with what Smith and Mapplethorpe achieved later, we have all of us stood there, just like that, on Coney Island.

EIRIN STØEN

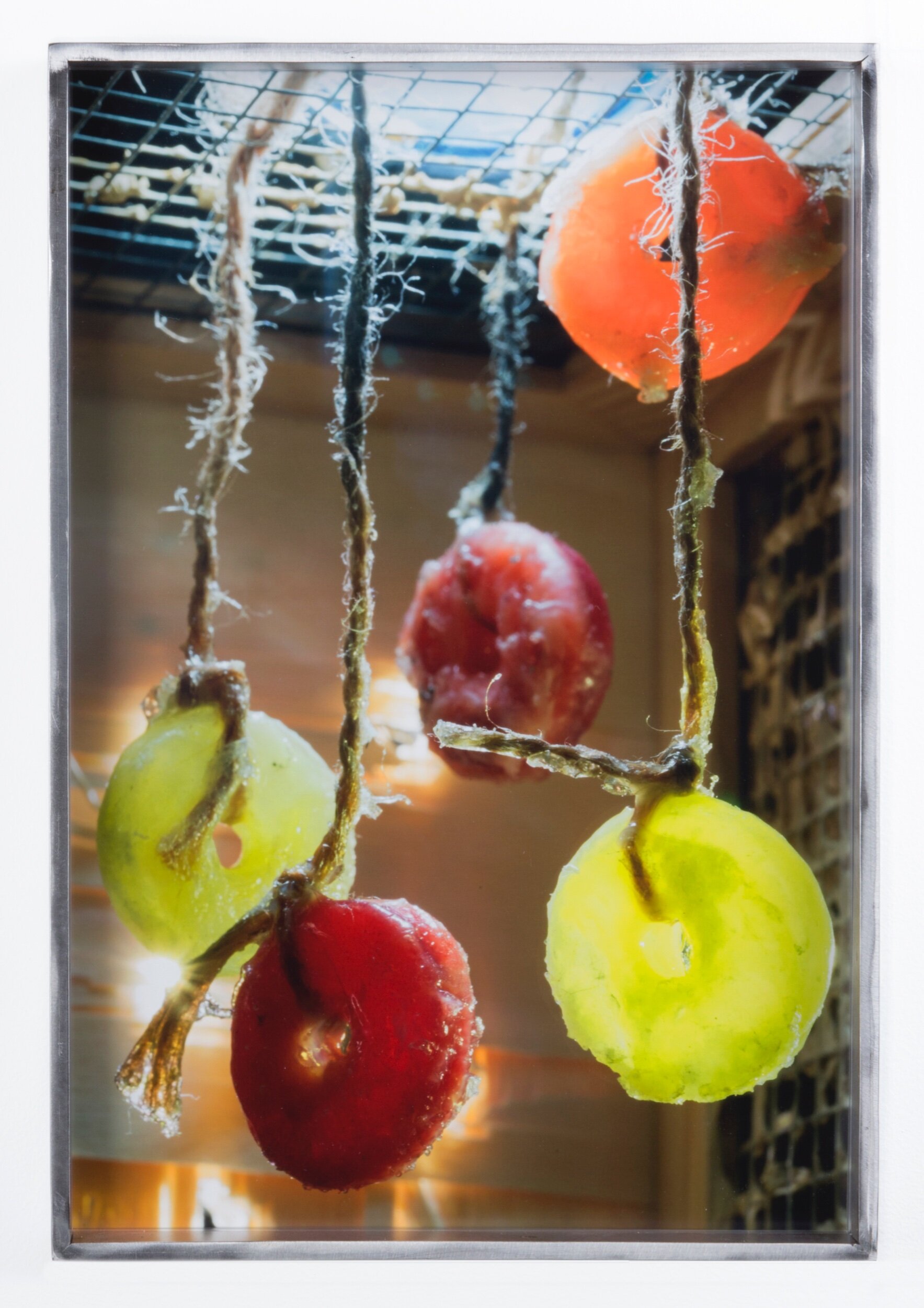

This is an image still processing in my mind, which isn’t a photograph on its own but a documentation of a work I haven't experienced, but which I still try to interpret. Ivan Galuzin invited Eirin Støen for a one night only at Brown Dude Projectspace. I didn’t make it in time to Sørligata's old factory premises in Oslo, but I’m nevertheless bewitched by the work as a photograph.

Afterimage by Maria Veie:

This is an image still processing in my mind, which isn’t a photograph on its own but a documentation of a work I haven't experienced, but which I still try to interpret. Ivan Galuzin invited Eirin Støen for a one night only at Brown Dude Projectspace. I didn’t make it in time to Sørligata's old factory premises in Oslo, but I’m nevertheless bewitched by the work as a photograph. Støen had, with simple means, climbed to heaven in Perfect Strangers (2010). A ladder of untreated wood, lashed together by wooden ropes that looked as if they were from the mountains, leaned against an open skylight window. I don’t know wether the audience could actually climb the ladder, but Støen as an artist had all the power in the documentary process, and makes the view part of her work. In the photograph that was shared on social media, we see a sun-filled, classical city loft, partly filled with old furniture. Støen's image makes a radical shift. Some would say that she’s s just built a ladder of rope and branches and set it up against a window. But the genius move to me lies in the choice of angle. The light from the skylight dazzles the viewer, making you feel enveloped in total darkness.

This contribution has been featured in a previous issue of Objektiv.

NAN GOLDIN

In 2001, Nan Goldin took photographs of a couple, Jens and Clemens, somewhere in Paris. Back then, no one knew what to expect, because they were waiting for something else. Back then, love was enough in many ways. It was all still playing out to the soundtrack of the 90s, when walls, fences, eastern blocks and cheap techno music fell to the ground, allowing people to meet at eye level in places that needed an embrace.

Afterimage by Tomas Lagermand Lundme:

In 2001, Nan Goldin took photographs of a couple, Jens and Clemens, somewhere in Paris. Back then, no one knew what to expect, because they were waiting for something else. Back then, love was enough in many ways. It was all still playing out to the soundtrack of the 90s, when walls, fences, eastern blocks and cheap techno music fell to the ground, allowing people to meet at eye level in places that needed an embrace. There were many places that needed embracing. The same year Goldin took her photos of Clemens and Jens, another war broke out. The war of fear. All wars bear their own name.

I was in Paris in January 2020. By then, Paris had experienced its own war. A war of pain. This war tore out everyone’s hearts. A war that seems impossible to win does this to you. At the airport, people were already talking about something coming. You should report any flu-like symptoms. I always have symptoms, if I'm asked. Not that I'm a hypochondriac. More because I have anxiety, and anxiety sets the symptoms in motion. I rarely travel alone because I have anxiety about that too, so I had my husband with me. We didn’t fail the test, so we could go to the old Jewish quarter. We’ve made a rule never to be in Paris without going there for a falafel. Only Tel Aviv and the Turkish area of Berlin can beat that taste. My husband says it’s the spice. I say it's the love. You can always taste it.

We were in Paris for a long time. We should have been there even longer, but something began to happen. It closed the world down. We flew back to Denmark in the middle of the night in March. I thought this war should have a name. I wrote down many suggestions in my notebook. I didn't need to find the culprit, to vilify a nation or a bat. Everyone has carried something with them of this war, in which we all, in our own way, became both soldiers and our own enemies. I thought we could learn something from it. Not the postulating platitudes of community triggered by retreating, staying at home in what quickly became our little fortresses. From there, we could engage in our own strategies and systems, deploying a cold, unhelpful militia that did nothing but fall into trenches that only got deeper and deeper. No, I thought, we could learn something else. I walked around the Danish forests, hoping we would learn something from them.

When I came back from Paris, I went into exile. I got to know the silence. That must be the name of the war. Because it created the spaces that I think we needed. We didn't need death. You rarely do. But we needed the pause. I've lived in a forest for a long time. A forest that's miles away from Paris and Nan Goldin. Far away from Clemens and Jens. But not from love. And I guess that's what we've learned. Not that this was or is the decade of love or fever. It's a different virus altogether. Silence has a different voice, a different war. We were wounded by those shots.

We all have someone we've lost. There are still many places that need an embrace. We know that again. And we’ve learned to act on it. So I hope that's what we will do. All of us from the old world who have moved on and have started living in a new world. When I came back to the city, I stood in my own driveway and embraced my husband. Nan Goldin should photograph it one day.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ

This is everything that is wrong with the world and how dangerous photography can intersect with it. The idea of a conflict zone as a backdrop for an Annie Leibovitz shoot for Vouge is vile. Posing the “First Lady” against a destroyed airplane in which people presumably died. Depicting a politician as an icon hero without any nuanced understanding of their function and complicity in this 155 day old brutal war.

Afterimage by Adam Broomberg:

This is everything that is wrong with the world and how dangerous photography can intersect with it. The idea of a conflict zone as a backdrop for an Annie Leibovitz shoot for Vouge is vile. Posing the “First Lady” against a destroyed airplane in which people presumably died. Depicting a politician as an icon hero without any nuanced understanding of their function and complicity in this 155 day old brutal war. A superficial glossy depiction of a hero in the Hollywood mould. The whole way this conflict has been covered (from the hierarchy of empathy we witnessed in the way white refugees were embraced) to the “cowboy and indians“ genre analysis of the actual conflict. Somehow deep down I think these pictures confirm our need for a binary understanding of the world as good and evil, for an outdated model of male heroes with their female enablers. All the while the faceless and for now nameless youth die daily. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not in any way supporting Putin but this shoot feeds into all the toxic heteronormative patriarchal ideas that make war inevitable.

Both images by Annie Leibovitz for Vouge.

This text was first published at Broomberg’s Instagram.

MAX DUPAIN

Whenever the word photography comes up, this image always comes straight to my mind. When I was introduced to the art of photography, around the age of 13, I was captivated by Max Dupain and the influential nature of his career – particularly his pioneering influence of modernism to Australia.

One Image by Julia Clark:

Whenever the word photography comes up, this image always comes straight to my mind. When I was introduced to the art of photography, around the age of 13, I was captivated by Max Dupain and the influential nature of his career – particularly his pioneering influence of modernism to Australia. For me, this image At Newport will forever be engraved in my mind. The composition, the leading lines, the shadows and the illusion of it being cut in half, are all so engaging and aesthetically complex that I find myself thinking about it all the time. All the subjects seem so perfectly propped that anyone would be forgiven for assuming it was staged, and the fact that it’s completely candid just speaks volumes about the skilled and watchful eye of Dupain.

One of the shapes that captures my gaze in this image is the shadow of the man standing in the middle. Despite his position being central in the frame, his shadow is as engaging to the eye, and even more so, it manages to compete with all the subjects as the most eye-catching aspect of the photograph. Aside from the shadow, this image has influenced me in so many ways, most notably the varied layers and textures in the image, the shapes and their interplay, and the objectification of the human subjects – making them shapes rather than people – their organic forms make the viewers eyes bounce from subject to subject making the image circular, causing the eye to view the image as a whole.

This image is even more interesting due to its positioning of a subtle undertow of social discomfort in an otherwise idyllic scene. There is something slightly unsettling about the disjointedness of the bathers, the hunched over, spine exposing stance of the man furthest to the left, the positioning of the man in the middle – looking as though he is bracing to hold back the weight of the ocean on the other side of the wall. Beach scenes, in Australian photography, are iconic for their imagery of the ideal summertime, but Dupain, in At Newport, very subtly challenges this norm, capturing both the glee of post war Australia, and the uncertainty of what was to come.

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN & LUCAS BLALOCK

I met Diane Severin Nguyen last August as she was passing through New York on her way back home to Los Angeles having finished the second of three summers on the MFA program at Bard College. Torbjørn Rødland, an enthusiastic advocate of Nguyen’s work, had suggested we meet. Nguyen’s visceral, materialist approach stayed with me. So last winter, when the 28 year-old artist was staging exhibitions of new work in both New York (at Bureau) and Los Angeles (at Bad Reputation) I was thrilled to catch up with her and talk more about her pictures, their fugitive subjects and how these two exhibitions came together.

Flesh before Body, 2019. All images here are by Diane Severin Nguyen.

ANIMAL, VEGETABLE, MATERIAL

A conversation between Diane Severin Nguyen and Lucas Blalock.

I met Diane Severin Nguyen last August as she was passing through New York on her way back home to Los Angeles having finished the second of three summers on the MFA program at Bard College. Torbjørn Rødland, an enthusiastic advocate of Nguyen’s work, had suggested we meet. Nguyen’s visceral, materialist approach stayed with me. So last winter, when the 28 year-old artist was staging exhibitions of new work in both New York (at Bureau) and Los Angeles (at Bad Reputation) I was thrilled to catch up with her and talk more about her pictures, their fugitive subjects and how these two exhibitions came together.

Lucas Blalock I want to start with a general question about the impulse to make these pictures. Where do they come from?

Diane Severin Nguyen It comes out of a desire to juxtapose physical tensions and the failures of their linguistic counterparts. Sometimes words can claim entire bodies with their symbolic force, but sometimes they’re nowhere near enough. Working within a non-verbal space can bring about very specific material qualities relating to touch. I work from these minute tensions, of being pressed on, pierced, pulled apart, submerged, falling, twisting, which are often related to pain. And I’m curious to see if they can be empathised with photographically, or how they can be transfigured into a different feeling.

LB The images are kind of ‘grunty’: they present more as sounds than as words. And this can be set in opposition to the central activity of the camera, which has been to show things clearly in order to enable one to name a thing.

DNS There’s a poetic impulse in that sense to rearrange the language, because photography’s claims to representation and the real should be the departure point for an artist. There’s also a lot of political potential in being immersed in a medium that claims so much accuracy, which helps me think through many different texts that deconstruct essentialist approaches. For instance, my title for the show Flesh Before Body at Bad Reputation came from Hortense Spillers’ words: before the “body” there is “flesh”. Which is to say that before there’s this symbolic unit there’s the substance that makes it up and fills in the parameters of the symbolic unit, and how that dis-individuated life-form is what makes possible the individuated one. So I began to ‘flesh out’ this naming process that the camera relies on for its power, and work against its trajectory of naming bodies by starting with the nameless. I was also thinking about the word ‘impressionability’ through this other text I was reading, The Biopolitics of Feeling by Kyla Schuller, which in one section emphasised the difference between the elastic and the plastic. When you apply force to a material that’s elastic, and then you remove that pressure, it will return to its original form. When you pressurise something that’s plastic, it will be permanently changed. So there are certain words that describe these physical tensions, and how they might affect consciousness.

LB Plastic strikes me as a very sculptural term, but you’ve folded these concerns into photography. Can you talk about the delimited space of photography in your work?

Wilting Helix, 2019.

DNS I like approaching photography as a set of limitations, and also as something problematic. It forces me to begin art-making from a non-safe space, and reckon with this very violent lineage of indexicality, the pinning down of a fugitive subject in order to understand and place it. But when those tools and thought processes are exhumed or applied uselessly, we can make this Cartesian method less confident of itself. To accept the impossibility of ‘knowing’ takes us somewhere else, perhaps a more intimate place.

LB The connection to the fugitive subject is really apt because your material choices seem to be directly addressing this kind of pinning down. There’s something about fragility or flow that comes up over and over again in your work.

DNS I think it’s a lot about the provisional – almost like a material or bodily extension of ‘the poor image’ as proposed by Hito Steyerl, but actually enacting that in all of its precarity. Materials and bodies slip in and out of contexts, permeable to the elements but also political contexts. I try to echo materially what I find unstable about images, and I try to observe how materials are photographically disfigured, alienated from ‘native’ environments. I try not to rest in the place of sculptural object-making for this reason. A moment of re-birth relies on the possibility of everything shifting at once.

LB Yes, in object making, the thing is in the room with you and has to behave and remain stable, whereas the space of photography and of pictures has another set of possibilities. To me, it sounds as if you’re kind of using the photograph against itself. You’re talking about its history of violence enacted through this objectifying tradition of isolating and making a subject.

DNS It’s like a process of essentialising. Which is problematic, but I see it everywhere around me. I guess the photograph has always been used in this way, but I see people trying to assign their identities optically. And I find this to be a dangerous space. I thought we’d worked past this, but maybe we’ll never work past it.

LB There is this other way of looking at it that suggests some potential. Because we’ve used it as a parsing machine or an indexer, there’s a way in which we’re willing to read the photograph back into a bigger space as a portion of ‘reality’. This is something we don’t often do with objects.