RAGNHILD AAMÅS

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

Afterimage by Ragnhild Aamås:

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

I thought I was beyond the effects of them, the images. We live in far too interesting times. But this one hits my inbox, in a newsletter from a newspaper I follow. I register it in my side-view while I'm working on a wooden figure.

It is not, I think, the aesthetics of the image, its sensuous reach, that strikes me, nor the indignation of the suffering, but rather a mimetic response that lands like a fist. A child sitting on her mother's lap, with a calm, almost angelic face. She looks the same age as my daughter EY. Like any other child, she is quite content to be on a parent's lap, regardless. The mother is hunched over, her face distorted by muscle and emotion, far from calm. Around her, women and children sit on the dusty floor, their wounds treated in various ways. In the background: a rubbish bin with a black bag, a plastic tube sticking out, empty packaging for bottled water, a five-litre container of some liquid in front of it, protected by cardboard. There is familiar street wear, dust-covered black backpacks on the floor, several darkened reflective surfaces of depowered screens. A bald man, propped up halfway between wall and floor, with bloody cotton swabs on his head, clutches a mobile phone, his face an empty field. As a group in a setting, they conform to what Susan Sontag quotes as Leonardo Da Vinci's instructions for showing the horror in a battle painting:

Make the defeated pale, with their eyebrows raised and knit, and the skin over their eyebrows furrowed with pain ... and the teeth apart as if crying out in lamentation ... Let the dead be partly or wholly covered with dust ... and let the blood be seen by its colour, flowing in a sinuous stream from the body to the dust (Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003).

I wonder if they have consented to have their pictures taken. I wonder in whose feeds the picture will appear, and with what caption.

Wait, there is something nestling in the stillness of the child's face: a quiet place, a silence, a projection beyond

Has motherhood, parenthood, the carrying of responsibility, rekindled in me a certain need to no longer ignore politics? Or let's put it this way: it seems to have attuned me to the fragility of things, to the integrity of the body, and to a certain stickiness of time (EY, who I'm calling as I type, has been intruding on me since she came home from kindergarten on the third day with an eye infection – and we have sterile saline water). There is a feeling of being turned upside down, but this is balanced by obligations of care, in the sense of Juliana Spahr, a micro-dose of contempt for the ethnostates and the ongoing governance of death.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag points out that suffering is always at a distance; in a sense, we can never be close enough. In the confrontation with images, there remains a central potential for empathy. But it is not independent of narrative and the ability to place oneself in the privileged position of having distance from immediate suffering, from the unfolding hierarchy in which the damage is received and captured.

Who is not in the picture? What is not depicted? What subject is not as easily captured as suffering? Could I imagine that the eyes of the child, who is certainly not looking at the lens, are staring at something beyond, at something responsible, at the ideology of nation states? Not somewhere else, but here.

Image: Aamås’ screenshot from inbox of newsletter showing photo by Mohammad Abu Elsebah / DPA / NTB). Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

SPARE RIB

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know. Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor.

Afterimage by Nina Mauno Schjønsby:

Certain Shadowy Parts

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know.

Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor. Written by women and focused on women's issues, the magazine addressed topics such as domestic violence, women’s mental and physical health, and the lack of equality in education and work. It was founded by two English women, Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott, in 1972. They were soon joined by others, among them Irish Roisin Boyd and Nigerian Linda Bellos.

One of the reasons why this image resonates with me, may be that it stands in for countless others that were never taken or published, images of other independent editorial teams emerging from marginalized or suppressed positions. Spare Rib, along with many feminist magazines both before and after, shows how people can create a space together – a micro-public – where they define what should be said and how. For me, this photograph represents the feminist community necessary to produce such a magazine. It also illustrates the solidarity, even in the midst of the disagreements that I know existed among them.

Today, Spare Rib has successors such as the London-based zine OOMK, which focuses on Muslim women, Belgium's Girls Like Us and Norway's Fett.

Editorial processes and the various stages of creative work are often invisible. Once a magazine has gone to press, its history closes in on itself. Perhaps this has always been the case. In my book Gi meg alt hva du kan (2024), I write about how, in the 1830s, Camilla Collett and her friend Emilie Diriks taught each other to write and explored the conditions of their lives through an intense correspondence. Their collaboration culminated in the handwritten magazine, which they called Forloren Skildpadde. In this way, two young women created their own intellectual space. This is Norway's first feminist magazine and an early forerunner of feminist publications such as Spare Rib.

I am fascinated by how, through intimate conversation and close collaboration, something bigger than oneself can emerge. Zines, magazines and small press publications still give a voice to marginalized perspectives and shed light on issues that might otherwise remain in the shadows – what Camilla Collett once called "certain shadowy parts.”

And there they sit, the editorial team of Spare Rib, the magazine that would survive until 1993, despite editorial disagreements and financial constraints. They occupy a place between a private sphere – their editorial office – and a public sphere – the street outside. For me, this image symbolizes how an intimate dialogue between friends or colleagues can be the beginning of something much larger: a multifaceted conversation that eventually turns outwards into the public sphere, branching out and reaching us even now.

TUNGA

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond. I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village.

Performance of Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós at Fundição Progresso, Rio de Janeiro 1987. Courtesy Wilton Montenegro and Instituto Tunga

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond.

I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village. The image is striking, impossible to miss - two young girls, in their teens, looking at each other, holding their long, shared hair in their hands. I can see their profiles, their noses. Why are they still together? They could let go.

I walk past a poster with a quote from Coco Chanel: ‘A woman who cuts her hair is about to change her life.’ I think of another friend who bleached his hair and claimed it would change everything. I wonder if it did.

Later, in a café, I search for more information about the twins and come across a description where the artist references a mythical text attributed to a Danish naturalist. As I scroll further, I learn that the conjoined twins were sacrificed upon reaching puberty, and that when a woman began to embroider with hair taken from them, it turned to metal and became gold.

On view in GROW IT, SHOW IT! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok at Museum Folkwang, Germany.

ELSE MARIE HAGEN

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's annual exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind...

Else Marie Hagen, Stilleben, 2023.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's Autumn Exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... The work was made after the artist repeatedly met a woman on a bus who 'looked deep into my eyes for a few seconds and down into my shoes.’

There is also Serina Erfjord's embroidered work from Dr Mahmoud Abu Nujaila's photograph of the last message on the notice board at Al Awda Hospital in Gaza: 'Whoever stays until the end will tell the story. We did what we could. Remember us.’ Or the phone call between Israa Mahameed and her mother, between Norway and Palestine, in A Random 13 Minutes, both keeping the conversation going amidst the terrible sounds from outside the mother's house.

These three works leave this writer in a certain state in the encounter with Hagen's still life. A photograph of the currently deaf and blind puppy trying to orient itself on the desk by the window where someone left it. Around it, a random clutter, which Hagen writes: ‘can be associated with a young person who might have something in common with the puppy.’

For what do we do, what can we do, the people inside in Gaza could see us as blind and deaf as this animal. They have every right to feel abandoned, nothing has changed in these past eleven months. The annual autumn exhibition aims to be a challenge by showing contemporary art, writing that: ‘Anything that shakes our sense of security seems provocative. Contemporary art is often such an unexpected encounter.’

When I look at this work, I'm reminded of a colleague's answer to his daughter's question about what he did in his studio all day. He said that sometimes he looked at a photograph he'd been making for a long time. When she asked him why, he said that for him the picture could work as a question mark, something for others to figure out, like this animal trying to understand the world. And then, if it really works in a provocative way, it can become something more, something bigger, something that can help change things. Like Hagen's. Possibly.

ROMANE BLADOU

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about. I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay.

Moving a house in Trinity Bay. Ca 1968. From the Collection: Resettlement Photographs, Maritime History Archive.

Afterimage by Romane Bladou:

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about.

I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay. It's being pulled by some small boats towards the hills in the background. And it was taken at a time when there was a policy of relocation, of resettlement within the province. People who lived in very remote places, in isolated parts of the Canadian coast, were asked, forced in a way, to leave their homes and peninsulas in order to move to places where there were jobs, hospitals and services. And they did this by floating their houses across the bay. The image stuck in my head. I had no idea you could do that. And it also felt so poetic. It was just this house floating to somewhere else. And I kept thinking that they would be living in the same home they had lived in all their lives, walking on the same floors, but with a completely different view outside the window every day. Even the light in the house would be different. Maybe they could see from the window where they used to live. I don't know.

In a way, I think what resonated with me is also this relationship to home, especially as an artist, we're always travelling. Maybe this image acts as a metaphor – it is about this desire to be anchored and grounded somewhere, but at the same time this constant pull to go to other places. So it's always in my head, I guess. In a different context, I wish I had a floating house.

ADAM BROOMBERG & RAFAEL GONZALEZ

What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

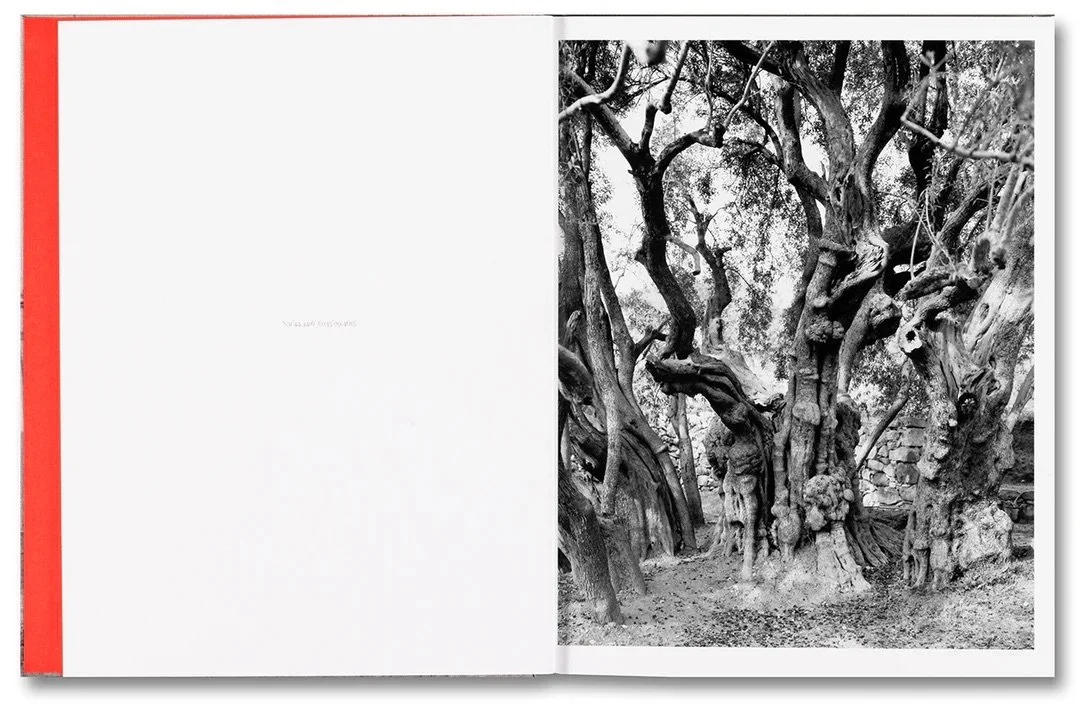

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

Afterimage(book) by Nina Strand:

We share posts in solidarity. We sign campaigns. We go to marches because doing nothing is not an option while this goes on. Today, I see a young couple who look as if they’ve just stepped out of a Woodstock film: long hair, loose clothes, seemingly free spirits. They stand close together. While a politician speaks into the makeshift microphone—no one can hear her—I continue to watch them. His moustache is like Salvador Dalí’s, his shirt is tie-dyed, he’s one hundred percent in character. I've seen him before, at another demonstration, but with a different girl. Is this how he dates, by proposing to meet at a demonstration? In any case, it’s for a good cause. I'm so fascinated that when the rally is over, I follow them into a café and find a table nearby.

In my bag I have the book Anchor in the Landscape by Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez: black and white photographs of trees in the Occupied Territories of Palestine. Each page has a photograph on the right and the geographical location on the left. A sentence about the book haunts me. Since 1967, 800,000 Palestinian olive trees have been destroyed by Israeli authorities and settlers. Eight hundred thousand trees... I read about olive trees. They grow slowly.

I overhear the moustache say that he used to cry when everyone shouted 'Let the children live' at the demonstrations for Palestine. Now he's worried about not shedding a tear. Has he become numb? The number of dead and missing Palestinians is unimaginable. I hear them talking about a friend who does nothing, no posts shared, no signatures. What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

When the woman tells her date that she struggles with sharing images of dead people, I almost join them at the table in agreement. I still worry about what it does to us to see them. I understand what a colleague said to me, that the Palestinian people want us to share, want us to see and understand. I share everything except pictures of lifeless bodies. When I wrote a post asking those with children to think about what they post, she told me off: ‘Who am I to decide?’, she wrote. I’m still not sure if she’s right. But I wonder more about those who do not share. I believe in doing something.

I actually got the date for today's demonstration wrong. I went to the square yesterday. It was just me and a Palestinian flag that someone had left behind. I spent some time there. Alone. Saying ‘Free, free Palestine’ several times. When I pass it on my way home, the flag is still there.

YOKO ONO

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Yoko Ono, installation view of Bag Piece, 1964, in “YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND” at Tate Modern, London, 2024. Photo © Tate (Reece Straw). Courtesy of Tate Modern.

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

There is a small statement next to the bag piece where the artist explains that you can see the world from it and talks about how when you are in a bag you become just a spirit or a soul, everything about race, age and gender falls away. The man in the bag sits very still, he might wonder where his girlfriend went, I see her looking more closely at the instructions on how to make a painting for the wind at the wall opposite.

After a while, the man emerges from the bag and shakes it a little before folding it neatly and handing it back to the museum assistant. That last gesture was like a more genuine performance my friend says.

We discuss trying it on, and I look back at the film, just as the same person cutting a hole in the bust is busy cutting off the bra. The film ends where the artist covering her breasts with her hands. It is shot in black and white, I wonder if she is blushing. It will still be me in the bag. There is no possibility of an escape. I suggest we move on.

JOAN JONAS

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

JOAN JONAS. Jones Beach Piece mirror on ladder, 1970, printed 2019. Photographed by Richard Landry. (The image found at Gladstone Gallery.)

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Being like Pippi Longstocking is no bad thing: her motto was, 'I've never tried this before, so I think I should be able to do it,' and this applies to so much of Jonas's pioneering work in video and performance. Later, in the museum shop, we see Jonas with her cane and dog in tow, here to give a talk. ‘What a fantastic show!’ I say to her in passing; she thanks me and moves on quickly, but that’s enough for me: just to see the woman who, according to the text on the museum's website, ‘began her career in New York's vibrant downtown art scene of the 1960s and 70s.’

I thought a lot about solidarity, generosity and a sense of community after seeing the show, and wonder where to find this today. Another colleague told me that he had visited Louise Bourgeois in New York, in her home, for one of her Sunday salons where she invited young artists. I thought of this, and of Jonas, when I later visited the exhibition Forks and Spoons at Galerie Buchholz, curated by Moyra Davey, where she weaves her stories and thoughts about each artist into the film that opens the show before we see the photographs. I wondered if I could find some of the old art scene spirit by visiting Francesca Woodman’s apartment in Tribeca. I learned from the film that Betsy, her old flatmate, still lives there, now with her 21-year-old daughter, in what she has jokingly called Grey Gardens. And another photograph, New York, New York, from 1977, by Alix Cléo Roubaud has some of Jonas’ playfulness: a big white canvas with a picture at the top of a small group of people in the park.

I'm thinking about what the strict customs officer asked me when I landed: ‘Are you here on business?’ and I said ‘Yes,’ but then his forehead wrinkled and I was worried mentioning anything about work might lead to not being accepted, so I blurted out: ‘Well, I'm an artist, here for the Art Book Fair. I'm not sure if a visit made by an artist with no money would qualify as a business trip?’ He didn’t find it funny and I should know better than to make a joke. But I could tell him now that this trip has made me very rich indeed.

JUMANA MANNA

Jumana Manna’s twelve-minute-long film, A Sketch of Manners (Alfred Roch’s Last Masquerade), 2012), was first shown in Ramallah, at the A.M. Qattan Foundation’s Young Artist Award 2012, where Manna won first prize. Drawing vectors between photographic image, historical re-enactment and geopolitical space, the film is particularly interesting in the way in which it re-imagines history.

SUBVERSIVE DREAM SPACES AMIDST THE ARCHIVES: JUMANA MANNA’S A SKETCH OF MANNERS

By Cora Fisher

A group of tragicomic masqueraders dressed in Pierrot costumes pose for their commemorative portrait to be taken. As they wait for the shutter to click, they address the camera, and through it, the long, piercing glance of history. They stare and fidget; they wait and rustle. The video camera pans across their heavily lined eyes and faces caked with white makeup. Finally, it stops to rest in the centre of the group, framing the portrait. With its patina of a bygone era, the fully frontal image recalls a vintage photograph, but the colour is decidedly contemporary, and the HD video camera captures the sitters’ movements, registering their tension. In this way, the moving image resuscitates the historicity of an early studio photograph, placing us firmly in the present.

Jumana Manna’s twelve-minute-long film, A Sketch of Manners (Alfred Roch’s Last Masquerade), 2012), was first shown in Ramallah, at the A.M. Qattan Foundation’s Young Artist Award 2012, where Manna won first prize. Drawing vectors between photographic image, historical re-enactment and geopolitical space, the film is particularly interesting in the way in which it re-imagines history. Its subject is an eccentric and over-looked dimension of the social life of a people now belonging to an unrecognised state and confined behind walls. It was inspired by an archival photograph of a masked ball held in Jerusalem in 1942, on the fateful eve of the nation’s dissolution, and depicts what the artist imagines ‘was to be the last masquerade in Palestine’. It offers a counter-narrative of Palestine through an anecdotal event.

The annual bon-vivant parties described by A Sketch were hosted from the 1920s to the 1940s by a landowner and merchant in Jaffa, Alfred Roch, who was also a member of the Palestinian National League. This cosmopolitan world dissolved with the dismantling of the country and its urban centres in 1948. Manna offers a decidedly romantic view of a bohemian microcosm, where theatricality and dreaming enlarge the psychic dimension of the photographic index. By way of this glimpse into a menagerie of upper-class Palestinians, A Sketch of Manners conjures the prelapsarian moment before the Nakba – ‘the disaster’ – which saw the expulsion of nearly 750,000 Palestinians from their homes and the 1948 Arab-Isreali war, a traumatic rupture shaping Palestine as the space of endless contestation and geopolitical erasure.

Scattered throughout the film are clues suggesting the mutual influence, in terms of cultural fantasy and dreaming, between Europe and the Arab world. A desk is strewn with Arab editions of European books, one by Charles Baudelaire, and the playbills and magazines of Egyptian Opera, cultural ephemera that also serve as archival mementos. Before the scene of the group portrait, the film opens with Roch sleeping on a couch after the ball, his make-up still thickly applied. The projected Orientalist fantasy imagined by the West is met with Roch’s inner dreamtime. A British narrator’s voice recites Baudelaire’s poem ‘A Former Life’, offering a somnambulant texture of fantasy: ‘Long since, I lived beneath vast porticoes … And there I lived amid voluptuous calms / In splendours of blue sky and wandering wave / Tended by many a naked, perfumed slave.’

To create the film and to deepen the understanding of the world evoked by the photograph, Manna consulted both private and public archives, as well as historians and sociologists including Dr Salim Tamari, Issam Nassar and her father, Dr Adel Manna. Her research yielded source images from the Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection held in the Library of Congress, which appear interspersed throughout the film (rather than simulated like the group portrait) as a foil for the film’s social context and the private dreaming of the protagonist. These include a photograph of a Middle Eastern merchant sipping tea with a group of British men, suggesting a detail from the biography of Roch, who was invited to the UK to speak at a conference on the Palestinian question. According to the story, he brought back the Pierrot costumes from this trip, attesting to the porosity between East and West that would be overshadowed by World War II.

This interplay between archival photographs and simulated scenes suspends the Palestinian bourgeoisie of the 1940s in a limbo between present and past time and space. Through the recurrent oscillating between static and moving images – between the external ‘fact’ of the indexical image, and the inward contemplative space suggested by the experiential image (the contemporary actors, the colour video medium) – the work re-animates the archive and offers up a third space – neither fact nor purely fictional – a psychic space of dreaming that is not Roch’s alone. A Sketch shows us how the artistic strategy of re-enactment invokes the lived dimension of history and the private life of politics.

Historical re-enactment is currently circulating heavily in art-world contexts, where historical tropes and content speak to the inheritances and conditions of the contemporary. Omer Fast’s 2005 film Godville, for example, used the site of a living-history museum in colonial Williamsburg to animate contemporary relationships to the imagined past of Virginia. In 2007, Nato Thompson curated ‘A Historic Occasion: Artists Making History’, a survey at Mass MoCA of artists interested in historical retelling, including Paul Chan, Jeremy Deller, Peggy Diggs, Felix Gmelin, Kerry James Marshall, Trevor Paglen, Greta Pratt, Dario Robleto, Nebojsa Seric-Shoba, Yinka Shonibare and Allison Smith. The exhibition took a materialist bent on historical revision, looking at how visual artists render history through objects, especially in a cultural climate where, according to Thompson, the ‘very idea of history seems under siege’ by historians rewriting the past, thinning attention spans, accelerated news cycles and amnesiac governments. In this exhibition, and in films like Manna’s that speak to the present through the past by referencing archival images or moments of historical rupture, one aim is to deliberately slow things down in order to sidestep these modern conditions.

In A Sketch of Manners, the overlay of a twentieth-century past and current events is palpable, if restrained. While we are afforded the spaciousness of historical distance, we can also understand Manna’s film as a direct commentary on the present. Other film and performance work takes up a more recent history of the last five years. Lebanese performance and stage artist Rabih Mroué, for instance, takes as his focus the current political unrest and protest movements throughout the Arab world. However, recent approaches to historical re-enactment can be observed not just in films, but also in paintings that refer to art history or create a historical imaginary that ties into the present. Emerging artists like Los Angeles-based Kour Pour, who recreates Eastern rugs through a process of transfer and erasure, retell a cultural narrative pictorially. The more archaeological, process-based conceptual paintings of Lebanese poet and painter Etel Adnan, recently included in Documenta 13, present a series of amalgamated objects and images that point to Lebanon’s 1975–90 civil war, when militiamen occupied Beirut’s National Museum, a reference that potently alludes to current events in the country.

The trend for using historical contexts as a vehicle to respond to the urgencies of current local and global protest movements and unrest means that the Middle East has been the historical locus du jour, with many film-makers and visual artists of this region circulating more widely on the international scene than they have done previously. Yet historical re-tellers are not always ‘native informants’ or cultural ambassadors hungry to broaden the cultural breadth and understanding of a Eurocentric West or an increasingly cosmopolitan and international art world. Sometimes, they are Western ethnographer-documentarians working with decidedly ahistorical approaches to storytelling. The striking release The Act of Killing (2012) by Joshua Oppenheim pushes documentary re-enactment towards the experimental, blurring the genre of documentary feature. Oppenheim’s implicit denunciation of the Western military-ideological projects of the Cold War and beyond focuses on the massacre, funded by the United States, of more than 500,000 communists and ethnic Chinese in Indonesia during the mid-1960s. The gangster Anwar Congo led the most notorious death squad in North Sumatra. Oppenheimer invites Anwar and his associates to re-enact the genocide as a theatrical dance macabre, using sets and costumes. The viewer is launched into the slippery terrain of Anwar’s trauma-afflicted psyche as he and his friends re-enact, in increasingly elaborate set-ups, their methods of killing. This performance of earlier crimes by living perpetrators proves that re-enactment is more than just a de-politicised visual strategy; it can convey the violent effects of politics better than any statistical abstraction. The re-enactors activate history as they re-write it in real time. The creation of a tertiary space of consciousness through the combination of documentary sources and artistic elements resurrects the depths of the collective unconscious.

More dreamscape than nightmare, it would be inappropriate to compare Manna’s film to such a full-length re-enactment. A Sketch concisely signifies the unconscious without actually exhuming its contents. (It is enough to hear Baudelaire’s lines and see Roch sleeping on the sofa, to extract the notion of dreaming.) Nevertheless, with its capsular view onto the past, it offers an account that gently defies the prevailing Western cultural bias, which sees the East as hardened by radicalism and categorically antagonistic to Western influence. Like the bon-vivant pleasantries of Roch’s last masquerade, the representation of the psychic space of the dream is a depiction that also runs counter to the expectations of dominant forms of historical narration. In Manna’s short film we find a world of pleasure on the brink of a tectonic geopolitical shift. With her deft transitions from archival image to personal imaginings, she offers a cavernous space that echoes with the traumas of the twentieth century.

LUCAS BLALOCK

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written.

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written. It kind of stopped me flat, and made me think about this time of immense shift and how the ascendency of photography had changed the world. It recontextualized what I was doing with a camera and tied it more deeply in to other structures—my experience as an American, and as my parents’ kid—and I thought maybe I’d been thinking about this photography thing all wrong, giving it short shrift, not taking as seriously as I might its contribution to our fundamental condition.

I am ‘here’ because it became undeniably evident to me that photography has been a central player in the world since then. Vilhelm Flusser writes in Towards a Philosophy of Photography that there are only two real turning points in human history— the invention of linear language, the basic building block of historical understanding, in the second century and the invention of the technical image, which mystifies historical thinking, in 1839. Photography has become a, if not the, lingua franca of the world I live in. The invention of photography and The Whale marked similar transitions into the modern. Ishmael’s world and ours became very different by the time they were done.

From Why must the mounted messenger be mounted? by Lucas Blalock. Order it here.

CLIFFORD PRINCE KING

This. Lying on a mattress, kissing. The poster on the wall trying to hold on. The uncertain installation, the importance of inclusion. There is so much in it. The statement of having the person portrayed on the wall. How this couple may or may not have discussed politics before they just had to lie down to get closer. At the top of the poster, a drawing. The face of a person looking down on them. The grapes in the corner, envious like me.

Clifford Prince King, Poster Boys, 2000.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This. Lying on a mattress, kissing. The poster on the wall trying to hold on. The uncertain installation, the importance of inclusion. There is so much in it. The statement of having the person portrayed on the wall. How this couple may or may not have discussed politics before they just had to lie down to get closer. At the top of the poster, a drawing. The face of a person looking down on them. The grapes in the corner, envious like me.

My friend sent it. It's from a show she's working on with another curator. They use the line: ‘Don't we touch each other just to prove we are still here?’ in the title. It is from a poem by Ocean Vuong.

The photographer has said in an interview that he gets inspiration from people-watching, stating: ‘It’s almost like seeing something precious happening, and as a photographer, you want to capture it, but usually, it passes by too quickly, so I try to recreate those kinds of moments but make them Black and queer.’

I remember a student I did a portfolio review with, she'd made a book on what love was and said it was because she didn't know. She was 23 and had never been in love. The book was full of pictures of couples cut out of advertisements. She couldn't find any real people in love. I know this by King is staged, but it is still truer than an ad. She should see this image.

From the upcoming exhibition at Princeton University Art Museum: ‘Don’t we touch each other just to prove we are still here?’ Photography and Touch.’ Curated by Susannah Baker-Smith and Susan Bright.

FRIDA ORUPABO

Frida Orupabo’s collages are based on personal archives and found online imagery, allowing her practice to take fluid shape like an absorbent and quickly adapting artificial intelligence, given access to the vast masses of the Internet.

Frida Orupabo, Batwoman, 2021. Collage with paper pins mounted on aluminum, 114 x 121 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin/Stockholm/Mexico City.

NAVIGATING WHITENESS

By Lisa A. Bernhoft-Sjødin

Frida Orupabo’s collages are based on personal archives and found online imagery, allowing her practice to take fluid shape like an absorbent and quickly adapting artificial intelligence, given access to the vast masses of the Internet. She explores her own blackness, and the points where the personal and the political cross paths. She states that: ‘I am interested in how we see things – such as race, sexuality, gender, family, and motherhood. How these concepts are understood and talked about, and how these ways of seeing affect us.’1

Frida Orupabo A lil help, 2021 © Frida Orupabo Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin, Stockholm, Mexico City

Orupabo’s Instagram feed @nemiepeba is her creative hub. Initiated in 2013, it mines her own personal archives as well as the vast Internet archives for dark imagery of slavery and colonialism. The feed plays with the notion of power by mixing and remixing personal and political imagery, but reads more like a search for selfhood than a political com- mentary.

Orupabo’s collages create narratives that are well known within the black and brown communities in Norway, though less so to the general public. These narratives expose the stories of the fragmented black body, at the same time as throwing light on the Norwegian condition, where both black and white voices seem to validate the superiority of Whiteness. By that I don’t mean white people, but the position that White culture holds in the global narrative of history and culture. Orupabo is acutely aware of how the White gaze has split the body of the Other into pieces, and moulded and distorted its imagery.

The photo collage (Untitled, 2018), exhibited in Orupabo’s exhibition Medicine for a Nightmare at Kunstnernes Hus in 2019, captures this state of emergency. It depicts a woman half clad in white, her other half exposed. She is standing, her front turned away from the viewer’s gaze, looking into the distance, her feet burning. It is an almost unimaginably melancholy work, exuding a longing for recognition and respect.

Orupabo’s recent but by now widely circulated individual paper cut figures are par- ticularly poignant. Physical and static manifestations of the Instagram feed, they are present- ed as individual pieces hung on the wall. Their gazes look you straight in the eye, loaded with pain and suffering, and transferring this pain to the viewer. They are clad in what looks like delicate white fabric, that conjures up both innocence and burial attire. Their multilayers are held together by paper clips, underlining that fact that these figures are fragmented bodies, easily manipulated and held together provisionally like paper dolls. They combine a variety of imagery to provoke new narratives, to examine and remix the past, to take control of their externally applied objecthood and emerge as autonomous subjects.

Frida Orupabo, image collected from her website.

I want these fragmented bodies, to defy objecthood and transform into subjecthood, but they don’t. Their gazes are not in control, not defiant, not proud, not challenging. The bodies remain objects, and instead of battling stereotypification, they seem to beg to be seen and their suffering affirmed. They’re violated bodies, robbed of selfhood and subjectivity. They reaffirm a readymade narrative of the era from which they derive. The selfhood that Orupabo is looking for is not there. Her figures remain surfaces, with no added internal meaning. Their gazes are hi-jacked by the normativity and neutrality of Whiteness.

Such work might well confront viewers with its spectacle, but it doesn’t challenge them. The fundamentals for this kind of discourse are not yet in place within Norway and giving this power to the White gaze means asking it to revise and rethink its own repositoryof images. This question might either be answered or simply ignored. This type of spectacle might not have any consequence for the Norwegian viewer’s self proclaimed empathy and anti-racism. In this way, Orupabo confirms what we already know: that Norway was never a part of this history. Consequently, her figures represent, present and portray the Norwegian condition with which we’re all brought up; they demonstrate a certain mindset with which we negotiate Norwegian Whiteness and the peculiar masochism that comes with it.

For Untitled, 2018, the work bought by the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Orupabo has taken her Instagram feed into the gallery through an iPad instal- lation. With its cacophonic intervals, Orupabo’s video work remixes the story of slavery and colonialism by combining it with footage of civil rights activists in American and South Africa, igniting new ways of seeing the black subject.

Her work contextualises a dire need for Scandi-Blacks to create a language to, at the very least, start a conversation about the kind of struggles with which we deal in Scandinavia without the masochism of trying either to be invisible to the white gaze or render ourselves as white as possible. As Sonia Sanchez asks in her poetry collection Morning Haiku: how to dance in blood and remain sane?

This text is from Objektiv #19. Published online on the occasion of Orupabo being shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2023.

WALKER EVANS

While the documentary image is haunted by the decisive moment, the studium calls for a more refined and contemplating dialogue. An unfinished message that seeks context in order to be read. Walker Evans seems to hold a special photographic gaze. Jean-Paul Sartre describes a person entering a bar and gazing through the locale, but as soon as the eye catches another eye, the gaze disappears, the magic is broken.

Afterimage by Bjarne Bare:

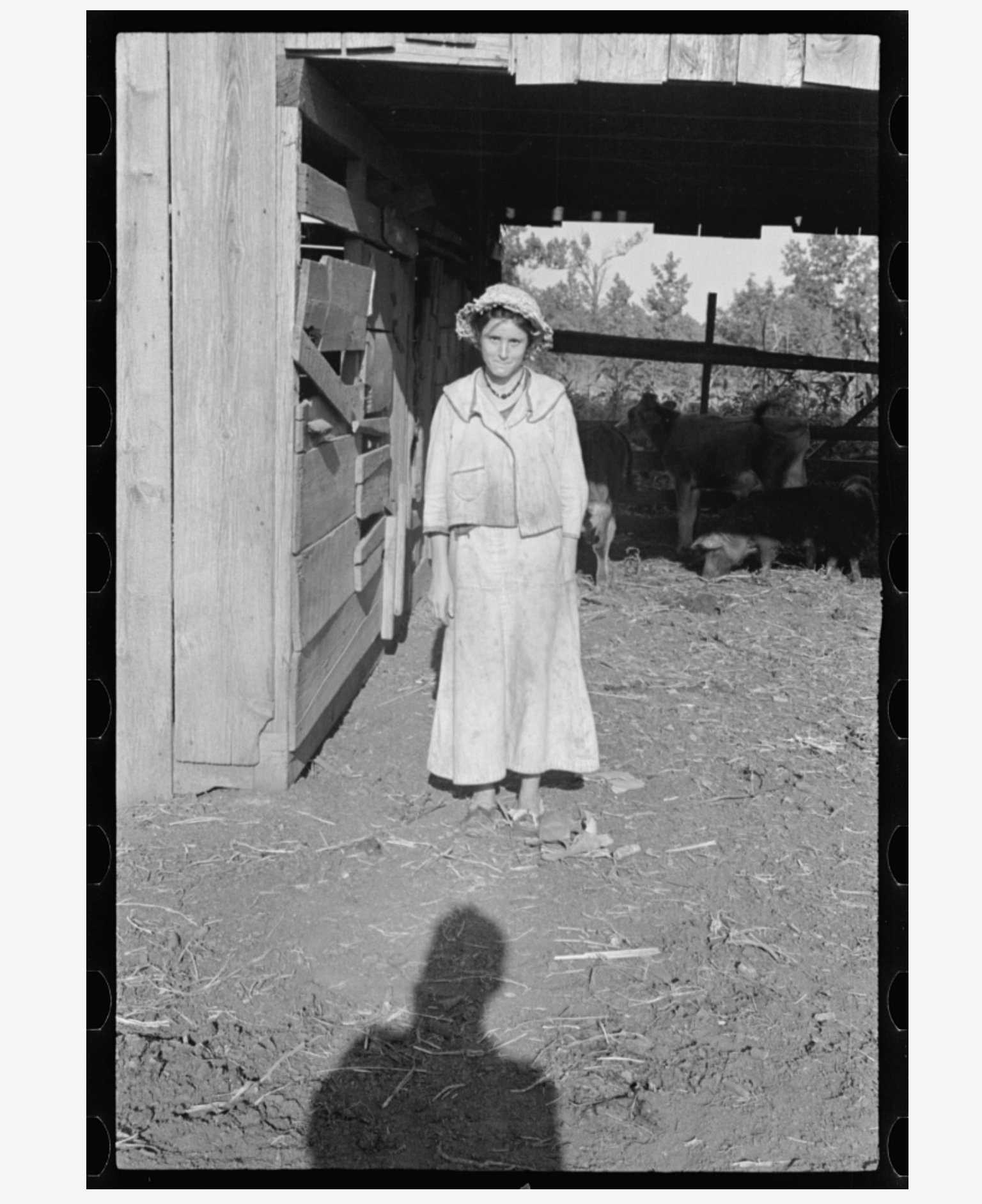

While the documentary image is haunted by the decisive moment, the studium calls for a more refined and contemplating dialogue. An unfinished message that seeks context in order to be read. Walker Evans seems to hold a special photographic gaze. Jean-Paul Sartre describes a person entering a bar and gazing through the locale, but as soon as the eye catches another eye, the gaze disappears, the magic is broken. ‘I no longer see the eye that looks at me and, if I see the eye, the gaze disappears.’ In such, I find Evans photographic work function as a pensive gaze more than a straight photographic document. Or as Lacan puts it: ‘In our relation to things, in so far as this relation is constituted by the way of vision, and ordered in the figures of representation, something slips, passes, is transmitted, from stage to stage, and is always to some degree eluded in it — that is what we call the gaze.’

When documenting Floyd Burroughs’ family and home for Let us Now Praise Famous Men in 1936, Evans’ isolated focus on the objects caught my eye. A chair flanked by a white sheet and a broom. An empty bed. A pair of workers shoes. Utensils. Along with the portraits he made, the closeups of details describe the life and situation more than the actual faces. As if, in the portraits, the gaze is broken. Along with the use of his gaze, Evans also distances himself from the traditional mode of documentary practice. There is little or no action in his photographs, yet we do experience the situation, through the focus on details. The images are silent, and their immanent communication is key. They are studies. In this, a photographic language develops, one which is more formal, perhaps, but also stays away from the usual photographic realism, where motion, portraiture and action is the modus operandi. When focusing on objects, such as the boots in the negative space, the empty bed, or the chair flanked by the broom and sheet, Evans lets the image breathe, look at you, rather than having the person in the image speaking. It is as if Evans trusts the image, the photography and its silence.

Walker Evans, Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Hale County, Alabama, 1936.

While writing this, I remembered seeing an image of Evans included in an exhibition at Standard (Oslo) in 2013. The exhibition included mainly contemporary work, and I was puzzled by the inclusion of the Evans piece. I am now, perhaps, understanding this better, as if it was an ode to Evans’ mind and eye. It is hard for me to define the postmodern project in photography, although it carries importance. I find the time we are in, photographically, somewhere in between modernity and postmodernity – and thus work created today should be informed by both. If a documentary approach still can be relevant, or at least exist, the straight photographic document is no longer enough – as if its naiveté is broken. Narration is no longer key. The images look back at us, and we are better informed in reading them now than ever before. In looking at Evans’ work dating nearly 80 years back, I have found relevant use and understanding of the photographic image. In Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Evans’ Friedlander-esque approach reveals something to me. Not only does he include himself in the image (there is a similar approach among his images of flood victims), but he also destructs the gaze, creating a similar effect as to the more recent Gazing Balls by Jeff Koons. The neutrality of the image is broken, the image looks back, and the photographer is present. This – what seems to be a simple snapshot – holds so many layers of photographic understanding. Along the other work by Evans’ it makes him a highly relevant photographer in the quest of understanding the potential for the straight image in a contemporary discourse.

TONY HANCOCK

This is a film still from the Tony Hancock movie The Rebel. A film about the accidents that lead to success in an art career and of ambition winning out to talent before once again giving way. It is a film about the ‘value’ of art, about patronage, about marketing art and about art’s frustrations as a vocation and career.

Afterimage by Clare Strand & Gordon McDonald:

This is a film still from the Tony Hancock movie The Rebel. A film about the accidents that lead to success in an art career and of ambition winning out to talent before once again giving way. It is a film about the ‘value’ of art, about patronage, about marketing art and about art’s frustrations as a vocation and career.

This comedy, for those who are not familiar with it, charts the journey of a bored junior businessman from London who daydreams of the bohemian lifestyle of the Parisian art scene of the late 1950s and early 60s. He chisels at concrete blocks in his small boarding house room to create his giant vision of Aphrodite at the Waterhole, and paints naïve canvases of birds in flight or a disembodied foot – all whilst wearing his artist’s uniform of a smock and beret. Eventually, he loses patience with the life he is born to and flees to Paris, where he accidentally gains success with his flatmate’s paintings and becomes the toast of the city. His ego becomes bloated and enjoys everything that this fame brings – including the credibility he craves, money and the adorations of the rich and influential. He is, despite this, a man in an alien world and ill-prepared for the part he must play. He is eventually found out as a sham – not one of the people who is born to this world of privilege and culture, but an intruder.

It was in 1992 on our first day at art school, in a college-wide screening of this film that we first met and talked. Strand handed a Softmint sweet to MacDonald and MacDonald broke a tooth on it. The message of the film and the trauma of Strand’s kind gesture left a big mark on us, and the discussion about what is art and what is not has been our constant preoccupation as MacDonaldStrand ever since. Our understanding of our position as intruders in a world we were neither born in to has also been constantly informed by this film.

TRAVIS DIEHL

The Dove of Criticism. At drinks after an off-off-Broadway play with the playwright and director, the conversation turned to the critics. So-and-so from New York Magazine had been in the audience that night. The New Yorker critic had canceled. The New York Times piece was out already. The playwright felt the review had been blasé, lukewarm at best—and since this was his first play produced after eighteen months in COVID-19’s grip, lukewarm felt downright icy.

The Dove of Criticism

At drinks after an off-off-Broadway play with the playwright and director, the conversation turned to the critics. So-and-so from New York Magazine had been in the audience that night. The New Yorker critic had canceled. The New York Times piece was out already. The playwright felt the review had been blasé, lukewarm at best—and since this was his first play produced after eighteen months in COVID-19’s grip, lukewarm felt downright icy. The director agreed, and said that something was missing in all of the theater reviews in that day’s paper, namely any nod whatsoever to the collective ordeal that we culturati, conversing in a heated plywood box built on a Brooklyn curb, felt was more or less over. Now, business as usual felt forced—critics could see their shows and write their reviews—and the bland reception of that fact called into question whether critics were glad to have survived.

Granted, good criticism is contemporary. But is it the critic’s job, post-COVID, to shunt every minor work into the pandemic’s frame? In the theatre world, a positive review in the Times drives a theater production’s ticket sales, and it makes sense that artists might expect critics to bow in the direction of their symbiosis. But visual art criticism is different. Here, art collectors take their picks on a private plane, shielded from casual visitors and critics alike, and insulated from the effects of reviews—in fact, any review, good or bad, blasé or raving, is more or less a notice, only a weak variable in the investment calculus of “buzz.” And anyway, most reviews publish after the show has closed.

Will there be art during the pandemic? Yes: there will be art about the pandemic. But the best COVID-era shows I’ve seen haven’t named the virus, which, after all, is only one more embroidery on the pattern of regular traumas. I’m glad to be writing reviews again. I never really stopped. Meanwhile, by summer of 2020, galleries large and small in Los Angeles and New York had lost no time banding together to build online “platforms”—Gallery Platform LA, sponsored by a bank; and simply Platform, underwritten by a megagallery. For once, even the cool galleries posted their prices. These websites are rafts on the sea of time, maybe; not stages so much as desperate efforts to survive the latest wreck. Also, as they float on, tacit acknowledgements that the waters won’t recede any time soon. Oh, but the dove of criticism carries yet its olive branch, pointy end down, eyes on the rainbow.

To mark the re-release of this popular title—with two additional contributions—we have republished this text by Travis Diehl.

TAYSIR BATNIJI

There is a face, I can see the eyes. The green and fragmented screenshot is divided into five. At the top I see a light switch. Then there is a green stripe covering the top of the face. Then I see the eyes looking back at me, before another green stripe. The bottom of the photograph shows the shoulders of the person the photographer is talking to. It looks like a woman in a halter top; it could be summer. Taysir Batniji’s book Disruptions shows screenshots of video calls with his loved ones in Gaza, taken between 2015 and 2017.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There is a face, I can see the eyes. The green and fragmented screenshot is divided into five. At the top I see a light switch. Then there is a green stripe covering the top of the face. Then I see the eyes looking back at me, before another green stripe. The bottom of the photograph shows the shoulders of the person the photographer is talking to. It looks like a woman in a halter top; it could be summer. Taysir Batniji’s book Disruptions shows screenshots of video calls with his loved ones in Gaza, taken between 2015 and 2017.

The light switch has such a prominent role in this picture. We never really see or notice it in real life. We just touch it, absentmindedly. I wonder if it is still there, if the house where this person lived is still there. In other pictures in the book there are streets, houses, more people, more life. There is probably nothing left. The word 'noise' is used in the press release about the images. It is true: they are noisy. Even more so – in some ways – than the images of Gaza shared daily on social media. We do what we can. We share. We watch it live. We cry with the parents holding the impossibly small white body bags.

At dinner last night a friend said that nothing can be saved at this point. We watched the reel of the doctor risking her life, running across a road to help a man who's been hit by a car. Another of a mother and child in the street. The mother is still. Hit by a sniper. The child is alive, and so there is a rescue. The child is carried to a doctor who runs with him to a hospital. We all know that the child isn’t safe, not even there, since the hospital might be hit next. There are no rules anymore. The Israeli politicians just carry on. I think of my friend from Tel Aviv who posts about the Israeli hostages. I think about them too, but this was never about what happened that October day.

The blurriness of Batniji’s images from Gaza came to mind when I saw the work of Mame-Diarra Niang at the Cape Town Art Fair this weekend. A work from the series Morphologie du songe (Morphology of Dreams) was on display at the Stevenson’s stand. Something Niang said in an interview about the series echoes the distorted screenshots: ‘This series feels like the abstract idea I have of myself, the acceptance that forgetting is also a starting point and a fleeting, necessary memory.’ I struggle with the idea of how to go on after seeing what is happening in Palestine, but I find comfort in reading these words in a country once torn by violence that now seems to be on the right side of history.

From the dedication on the first page of Batniji's book, we learn that he lost his mother in 2017. Since the beginning of the Israeli bombardment in 2023, he has lost 52 further members of his family. Tell me, what do we do now? We continue protesting, watching, sharing these disrupted images that haunt us. As Taous R. Dahmani writes in her essay at the end of the book: ‘Photography’s (absurd) quest to “tell the truth” might actually lie in fables, not realism. The abstract value of the glitch establishes a new type of document: evidence of the instability that rules over the Palestinian people, and of the survival of images, despite it all.’

Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024. With the essay On What Subsists and What Persists, in French, Arabic and English, by Taous R. Dahmani. Designed & Published by Loose Joints. All profits go to NGO Medical Aid Palestine.

BERENICE ABBOT

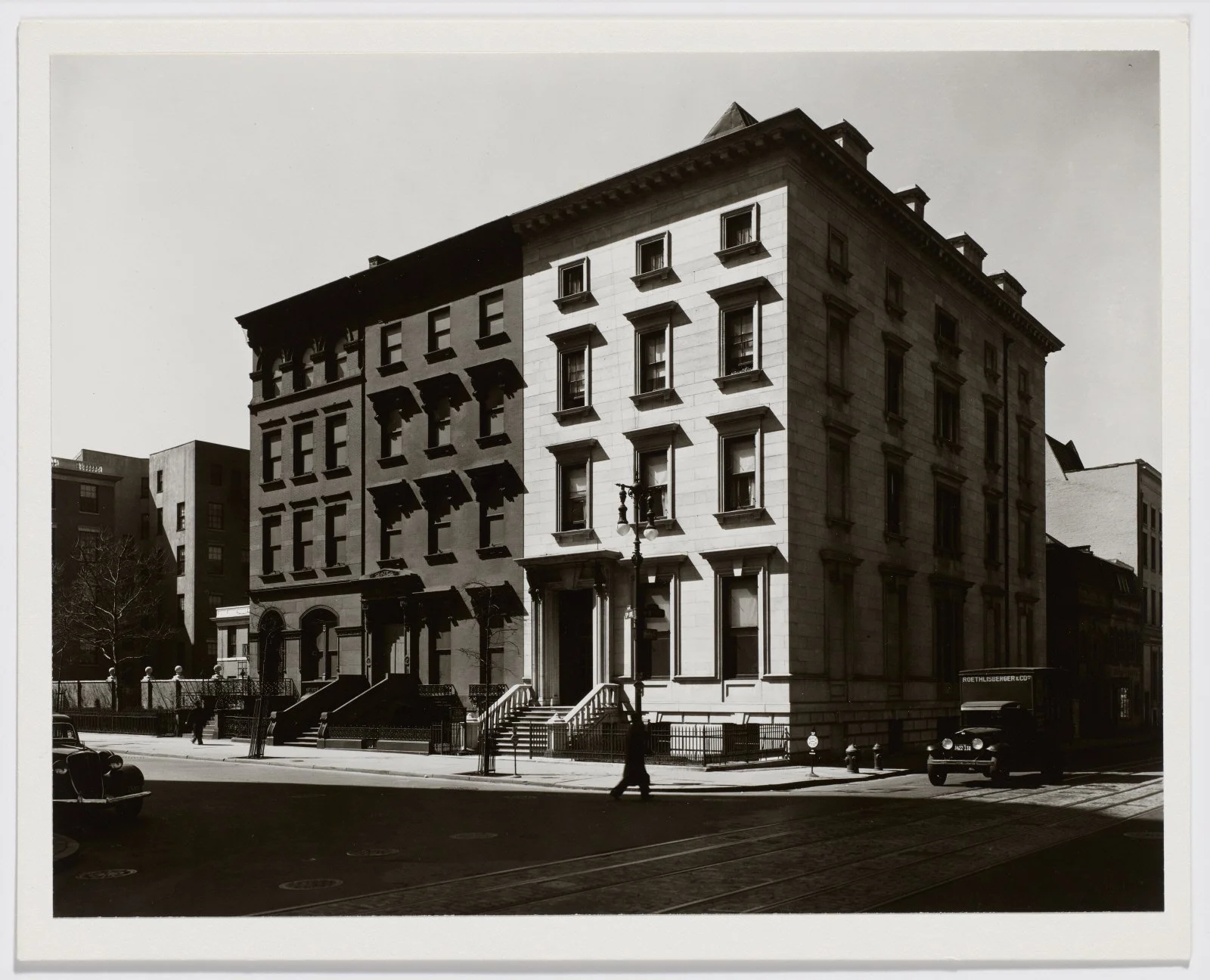

This photograph by Berenice Abbott from her astonishing project Changing New York (1935–39) has been my desktop background for the past five years, as it reflects my interests in the urban landscape, biography, affect, paratexts, composition, and technique. As with other photographs I love, I secretly wish I’d made it, despite the temporal impossibility.

Berenice Abbott, Fifth Avenue, nos. 4,6,8, New York, 1936, printed 1982, Gelatin silver print. Gift of A&M Penn Photography Foundation by Arthur Stephen Penn and Paul Katz, 2007. The Clark Art Institute, 2007.

Afterimage by Arturo Soto:

This photograph by Berenice Abbott from her astonishing project Changing New York (1935–39) has been my desktop background for the past five years, as it reflects my interests in the urban landscape, biography, affect, paratexts, composition, and technique. As with other photographs I love, I secretly wish I’d made it, despite the temporal impossibility. I admire the picture’s power of suggestion: the stark tonal contrast between the occupied brownstone and its (boarded-up?) neighbours seems to be a commentary on social division and economic marginalization, or perhaps more symbolically, a parable for societal good and evil in and the proximity of these two poles. However, the caption that appears in the 1939 publication of the series complicates such a straightforward interpretation of the photograph: “Built in the mid-eighties for three Rhinelander daughters, the houses at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street present a rising curve of elegance. Henry J. Hardenbergh, architect of the old Waldorf-Astoria, the Hotel Albert and the Third Avenue Car Barns, designed all three. No. 8 was once the home of the art collection which formed a part of the original Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

The history of the buildings does not reflect the social division that a cursory look might suggest. A related close-up, for instance, shows the grandeur of the marble masonry entrance of No. 8 obscured in this wide shot. We can only speculate on the meaning of the other details not mentioned in the caption: the truck’s company name, the broad and slender water hydrants standing next to a dwarf bus stop sign like the lineup of a comedy troupe, or the spatial connection between the tram tracks, the sewers, and the two cars that bookend this NOHO corner. The original caption by Elizabeth McCausland – recouped by Sarah M. Miller in her recent book Documentary in Dispute – stresses the element of economic privilege even further, stating that the corner brownstone was “the first marble house built in the city,” but also asserts that the moral values represented in the picture are more ambiguous than the bright contrast suggests.

This image has been printed in slightly different ways, as it used to be more common in the past. The Museum of the City of New York, which houses part of the project’s archive, has nine prints of Fifth Avenue Houses, Nos. 4, 6, 8. One of these is a contact print made from the 8x10 inch negative with a distinct sepia tone and less contrast than the enlargements. As such, the potential for the buildings to serve as an analogy for prosperity and hardship gets diminished, a reminder that technique can also define meaning. It’s easy to get lost comparing the different versions of this image in American collections and the variety of their particularities. Some bear a Federal Art Project stamp on the verso; others feature Abbott’s signature and the recto; some are vintage prints, while others were printed as late as the 1980s in a much larger size (20x24 in) by the artist’s estate, etc. From what I can appreciate online, the print at The Clark (pictured here) seems to be the most tonally balanced, although the version in the book is even darker.

I’m interested in how Abbot’s project is unsentimental but not neutral. She tried to convey a resentment for the loss of vernacular architecture and the ways of life that depended on those buildings. Her reputation and biography have become inseparable from the content of those pictures and the history of those sites (for instance, the building on Greenwich Village where Abbott and McCausland lived while making Changing New York is listed in the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project). As the historian Bonnie Yochelson reminds us, “it was her story as much as her photographs that captured the public’s imagination and made her an art-world celebrity.” This amalgamation of art and life has persisted over time, as publications and exhibitions consistently reference the anecdotal dimension of the work, which is now perceived to reflect the artist’s desires with great authenticity. For me, Abbott’s ingenious use of natural light in Fifth Avenue Houses, Nos. 4, 6, 8, and the abundance of details the scene offers articulates her sensitive perception of the urban landscape, resulting in a complex picture in which the elements you see, what they suggest, and what the artist intended them to communicate go in different yet strangely complementary directions. “Pictures”, wrote Abbott, “are wasted unless the motive power which impelled you to action is strong and stirring.” I’m grateful for her intricate motives, which produced a picture so full of life.

MYRIAM BOULOS

Sisaruus. Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger with Elif Erdogan: When we talk about feminism, let’s talk about love.

Let’s start with feminism and define it as a social and political movement that seeks equality and challenges the gender-based societal norms and expectations that can limit people. Feminism gets its power from the drive to create a society that is fair for people of all genders.

During the past four decades, the definitions of feminism changed frequently as feminist discourse and activism expanded. In the ’60s and ’70s, feminism prioritized issues like reproductive rights and women’s workplace equality. Since the ’90s, feminism has emphasized global diversity and intersectionality with other social movements, including those fighting for trans rights and sex- workers’ rights. This breadth and diversity is crucial to feminism today, which addresses issues of gender, race, class, ability and sexuality. Technology has played a significant role in this expansion, with the rise of feminist blogs and social-media activism allowing for wider dissemination of feminist ideas and lowering the barrier to organizing.

Myriam Boulos, What’s Ours, 2023. From the current Festival of Political Photography 2024 at the Finnish Museum for Photography in Helsinki. Myriam Boulos is part of this festival.

Sisaruus. Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger with Elif Erdogan:

When we talk about feminism, let’s talk about love

Let’s start with feminism and define it as a social and political movement that seeks equality and challenges the gender-based societal norms and expectations that can limit people. Feminism gets its power from the drive to create a society that is fair for people of all genders.

During the past four decades, the definitions of feminism changed frequently as feminist discourse and activism expanded. In the ’60s and ’70s, feminism prioritized issues like reproductive rights and women’s workplace equality. Since the ’90s, feminism has emphasized global diversity and intersectionality with other social movements, including those fighting for trans rights and sex- workers’ rights. This breadth and diversity is crucial to feminism today, which addresses issues of gender, race, class, ability and sexuality. Technology has played a significant role in this expansion, with the rise of feminist blogs and social-media activism allowing for wider dissemination of feminist ideas and lowering the barrier to organizing.

When we talk about gender, let’s talk about gender minorities

The concept of gender is integral to discussions of feminism. Gender refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, expectations, and identities associated with being male, female, trans, or non-binary. It is influenced by social and cultural factors. Gender is a fluid and dynamic concept; it varies across cultures, societies.

Despite the widespread movement for gender equality among feminists, until recently there has been a lack of attention to gender diversity within the movement itself. The related lack of language around this issue is one factor hindering a deeper understanding of it. This is a significant gap, given the marginalization and discrimination experienced by people who do not conform to traditional gender norms.

Feminist critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s concept of “strategic essentialism” proposes that marginalized groups can re-appropriate, as a means of political action and mobilization, the essentialist narratives or identities that are used to exclude or oppress them. In this way, people fighting patriarchy can join forces to unite with and empower each other. To create a more inclusive and intersectional movement for true gender equality, let’s acknowledge gender diversity as a central part of feminism.

When we talk about women, let’s talk about intersections

The term intersectionality was coined by human-rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw and first used by Black feminists in the late 1980s. The concept describes how different social categories, such as gender, ethnicity, sexuality, or class, interact and overlap, resulting in compounding effects. When feminism, as a social and political movement that advocates for gender equality, employs an intersectional strategy, it can address how certain forms of oppression impact people differently according to their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or other factors. Intersectionality provides a way for those who have been typically excluded from discussions about women’s rights—such as BIPOC women and trans people—to have their voices heard and their needs addressed. Intersectionality recognizes that different forms of oppression are interconnected and cannot be examined separately from one another. By centering intersectionality in feminist discourse and activism, the movement becomes more inclusive and effective in addressing systemic oppression.

Some feminists are apprehensive about intersectionality, fearing that it is a threat to their agenda. They feel, for example, that championing trans rights in the context of feminism can negate the notion of womanhood when there is still far to go to improve women’s rights. However, we believe the battles for women’s rights and trans rights are interconnected: they both aim for bodily autonomy and gender-related healthcare and fight concepts such as gender- based violence and strict gender roles. By working together, both groups strengthen their efforts to promote equal treatment and representation in areas such as employment, education, healthcare, and politics.

When we talk about history, let’s talk about language

Artists working fifty years ago spoke about their work and their relationship to gender and womanhood with different words and in different contexts

from the ways we speak about them today. Since language is constantly changing, its use can be problematic. As the curatorial team, we worked hard to understand the contexts of the particular time and place in which these artists entered the debate about gender diversity. When we observe patriarchy and how it works, let’s look at how women have lived and have been treated throughout history. But at the same time, let’s talk about the present and how history relates to contemporary ways of discussing gender in a broader sense. Language is nuanced and an important tool—for example, when minority groups discuss their positions, identities, and struggles.

When we talk about women, let’s specify which women we’re talking about. If we’re discussing, say, white women in a particular part of Europe, let’s mention that—and the parameters that go with it. If we talk about women as a gender, then we also talk about transwomen. And when we talk about people who have grown up within patriarchy, we talk about all people. Different people from different backgrounds and experiences have different lenses on the social situation and different languages to express their views. When we write or say something in a public space, let’s use inclusive and specific terminology.

When we talk about feminism, let’s talk about love

We still sometimes hear that feminists hate men, but this is neither true nor useful. Feminism is a movement based on justice and equity, both of which stem from the notion of love. Feminism does not stand against a particular group or individuals but rather seeks to address and combat the structures of sexism, gender inequality, and discrimination in all forms. These issues are not caused by any specific enemy, but by social systems, beliefs, and patriarchal structures that perpetuate injustices and inequity. We are all impacted by patriarchy, no matter our gender. All of us, men included, navigate our society’s dominant gender roles and expectations; we all internalize patriarchy. It is comparable to the situation in which white individuals benefit from racist ideologies even if they do not consciously subscribe to them. These systems are perpetuated through socialization, media representation, and institutional structures that normalize and reinforce particular values and beliefs. Intersectional feminism works toward gender equality just as it campaigns for racial equality and equity for all people.

Let’s dismantle the patriarchy and create a more equitable world for all genders to give and receive love.

This text from Objektiv #27 is based on a conversation between curator Orlan Ohtonen and director Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger from the The Finnish Museum of Photography. Published online in order to highlight the ongoing Festival of Political Photography 2024 at the museum. In Finnish, ‘sisaruus’ is a term with no gender-based connotation. The word is derived from the feminine word ‘sisar,’ (sister), but when used as a noun ‘sisaruus,’ it can equally refer to any gender.

SOPHIE CALLE

I am thinking of the video work Voir la mer by Sophie Calle which I saw yesterday at the Musée national Picasso-Paris. Six videos of Istanbul residents seeing the sea for the first time in their lives. They are filmed from behind, looking at the sea. Then they turn around. One of them is very self-conscious in the beginning, looking into the camera.

During the ceasefire in Gaza, the Palestinians were told it was forbidden to go to the sea.

Sophie Calle, Voir la mer, 2011.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

I am thinking of the video work Voir la mer by Sophie Calle which I saw yesterday at the Musée national Picasso-Paris. Six videos of Istanbul residents seeing the sea for the first time in their lives. They are filmed from behind, looking at the sea. Then they turn around. One of them is very self-conscious in the beginning, looking into the camera.

During the ceasefire in Gaza, the Palestinians were told it was forbidden to go to the sea. Among all the atrocities, I still think about that. I can't see the reels of shaking children, I talked about it with a friend here in Paris who told me it was the same for her, but that she knew what was happening without seeing, that she had all the images of the war in her heart without having observed anything. I decided to lean on this faith and instead share other testimonies from the crisis. Like Chris Hedges’ speech about how we are failing the children of Gaza. He cries as he speaks.

I think about the way the Turkish people look into the camera. It reminds me of Kim Hiorthøy's exhibition Jeg er nesten alltid redd (I'm almost always afraid) at Fotogalleriet in 2003. Hiorthøy asked his friends to stand in front of a Super-8 camera for the duration of the roll of film. For three minutes you can look at these people and see all their thoughts, fears and self-consciousness seeping out of them. I think about the fear that we all carry within us.

I am going to a dinner tonight and there has been an email exchange about what to bring. A Frenchman replied that he would bring all his feelings. Me too.

SEIICHI FURUYA

One of the books in my suitcase after my stint at the Polycopies book fair during Paris Photo was Our Pocketkamera 1985 by Seiichi Furuya. After clearing out his attic, Furuya found films from a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera he had given to his wife Christine in 1978. She continued to take photographs until she took her own life in 1985. This book contains mainly pictures taken by Christine, Furuya and their son Komyo, together with texts written by Furuya.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

One of the books in my suitcase after my stint at the Polycopies book fair during Paris Photo was Our Pocketkamera 1985 by Seiichi Furuya. After clearing out his attic, Furuya found films from a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera he had given to his wife Christine in 1978. She continued to take photographs until she took her own life in 1985. This book contains mainly pictures taken by Christine, Furuya and their son Komyo, together with texts written by Furuya.

The blurry image of the sliced pineapple on the cover and the portrait of Christine holding the pineapple and looking lovingly at her son, has been on my mind these days as I watch the horrific images of parents holding their murdered children in Palestine. Christine's struggle with mental illness is no secret throughout the book. There is also a striking juxtaposition of image and text that I’m still thinking about, she is standing on a balcony waving to the photographer, and we see many new flower pots on the balcony ledge. This is a still from a Super 8 that Furuya found in 2018. As he writes: ‘She started her life in East Berlin by inviting spring to her home, full of hope for a new beginning.’